New Employment Rights Act ‘a huge boost for women in the workplace’: A rare bright spot in the smorgasbord of disappointment from the UK’s Labour government.

Recently I read:

UK must stockpile food in readiness for climate shocks or war, expert warns: ‘The first UK Food Security Report in December 2021 found the country was 54% food self-sufficient’

Latest posts:

Once again, managing a government budget is not like managing a household budget

I always appreciate seeing a reminder as to why, despite what politicians from several parties insist on telling us, managing government spending is nothing at all like managing a household budget. And thus, the logic you use when doing so should be entirely different.

What you need to do to act as a ‘responsible’ householder under the present framework is different to what you need to do to act as a responsible government minister. Pretending that they’re the same thing is irresponsible (and in fact often represents a misunderstanding of how sensible people do manage household budgets).

Aditya Chakrabortty provides a nice quick summary of many of the relevant factors in an article from today’s Guardian called ‘The cynical spectre of Osbornomics is haunting the Labour party':

…unlike individuals, nation states don’t retire or die; that no household hides a government’s printing press or tax department in its loft conversion; that most families do borrow to invest (for what else is a mortgage?) and will spend cash to keep kids from going hungry

These aren’t the only reasons. A couple more that come to mind include:

- The choices a household makes tend to impact only themselves to any large extent. The choices a government makes can impact the whole nation, its whole economy.

- If a household doesn’t buy a luxury holiday this year then it doesn’t necessarily affect other aspects of their budget. It just saves the holiday money. Whereas cuts to public service costs in one area for example often lead to rises in expenses for other area. A classic example of this would be a reduction in GP services tends to lead to an increased demand for (more expensive) hospital services. Sacking 1000 civil servants? That’s 1000 more people who may require benefit payments, training, education et al for a while.

This doesn’t mean a government in a country with its own currency operates with no constraints of course. Liz Truss’ rapid destruction of our economy proved that.

They’re just different, usually lesser, constraints. And at the end of the day, if it needs money to solve any given emergency, it has that money if it chooses to have that money.

An AI company reinvents the concept of a 'friend'

One of the increasing morass of “throw it all against the wall and hope it sticks” AI companies appears to think they have invented this new concept called “friend”. Well, actually it’s probably the fact that they think they’ve invented a reasonable substitute for the existing concept of friends that’s the unsettling part.

It has a very premium URL - friend.com - which I imagine might have cost more than the amount of revenue the product makes if we’re lucky, although I have my doubts.

Just in case it dies the death I hope it does: it’s advertising a crappy-looking plastic necklace thing that listens to what you say. Then you have to get your phone out so it can send you a text in response at various points in time.

The more useless half of a smart-speaker, kinda? Not according to the makers. It’s your friend. Literal friend. Which makes for a hilarious FAQ with “frequently” asked questions including “When will I receive my friend?” and “How much does friend cost?”.

One percent of me looks at this stuff and thinks maybe, just maybe, there’s a temporary use for this stuff in acute situations, if run for reasons other than idle profit. It’s possible I am just an old man raging at the wind, misguided in an adherence to the appeal-to-nature fallacy.

After all the loneliness epidemic seems to be real, and occasionally deadly. Experiences like those we saw when Replika lobotomised everyone’s girlfriends show that some users do form deep bonds with AI entities. It just doesn’t feel like this is the general, long-term, solution we need. Apart from anything else, this instantiation of the idea seems cumbersome, and if you break it, the company decides to stop supporting it or starts charging an extortionate subscription for it then your friend just died.

We didn’t always have a loneliness epidemic, and it wasn’t because Victorians wandered around town dressed in their top hats and gimmicky plastic necklaces. At the very least, please, please, do and show the actual, rigorous, universally acclaimed research to show that these things do good and do not do harm in the short and long term before foisting them upon an increasingly desperate population. It surely wouldn’t be hard to get funding for that.

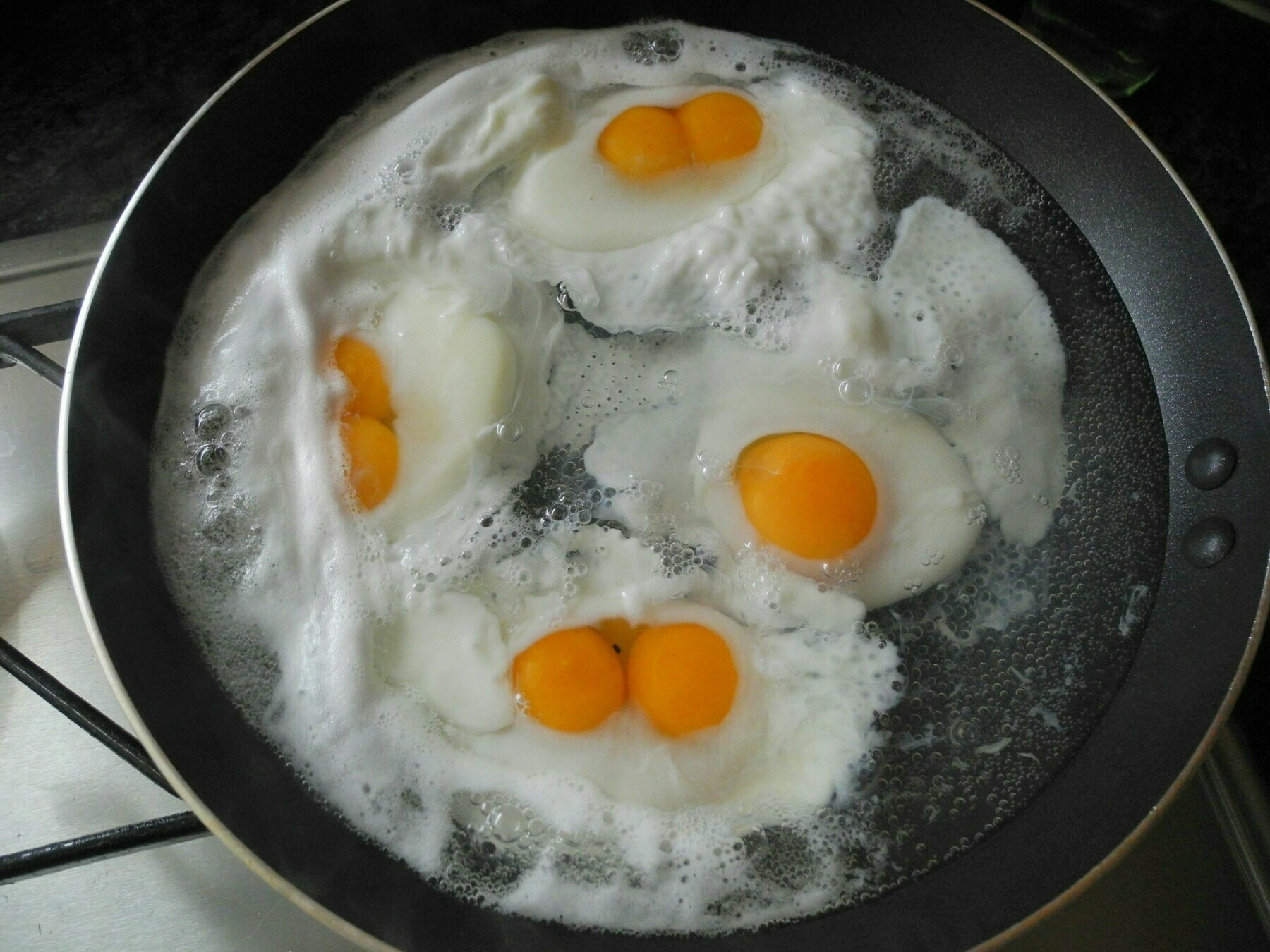

A spate of double-yolked eggs

Nine of the last twelve standard supermarket eggs I’ve cracked open had double yolks. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen even a single egg like this before.

What could this mean? Is it another sign of an impending Armageddon?

(Photo by Chris J Walker on Unsplash)

Well, tradition-wise, there’s a variety of options depending on your affiliations. At least according to Sauder’s Eggs:

- Norseman thought that double-yolk eggs meant someone in your family is going to die. Oh dear.

- Wiccans believed that it’s a sign of future good fortune for the egg-cracker. I think I’d prefer to go with this one.

- In some cultures, it’s supposedly a sign that a someone you know (or you yourself) is going to become pregnant.

How often do double-yolks occur? Well according to Dr Karl Kruszelnicki, if you average out the rates from chickens of all ages than 1 in 1000 eggs would have two yolks. So have a experienced a one in many many trillion life event - far rarer than a lottery win?

Well, not necessarily. The way modern egg-farming works means that at a box level double-yolks are not an a statistically independent phenomenon. Eggs of a certain size, from hens of a certain breed or age, or those having experienced certain patterns of light exposure are more likely to be doubles. And distribution networks tend to box up eggs by size and flock - so if you find one you’re much more likely to find another.

This is to the extent that M&S started offering boxes of 100% guaranteed double yolkers for sale. Admittedly at a cost, because to satisfy the guarantee the eggs needed to be “candled” first.

Besides 9 out of 12 isn’t anywhere near the most extreme recorded case. One of my fellow countryfolk apparently once opened a continuous sequence of 29 out of 29 double-yolked eggs (not, of course, from guaranteed double-yolk boxes, that would be even more irrelevant news than this post). And as for a single egg, well, the current world record appears to be an egg that contained an astonishing nine yolks.

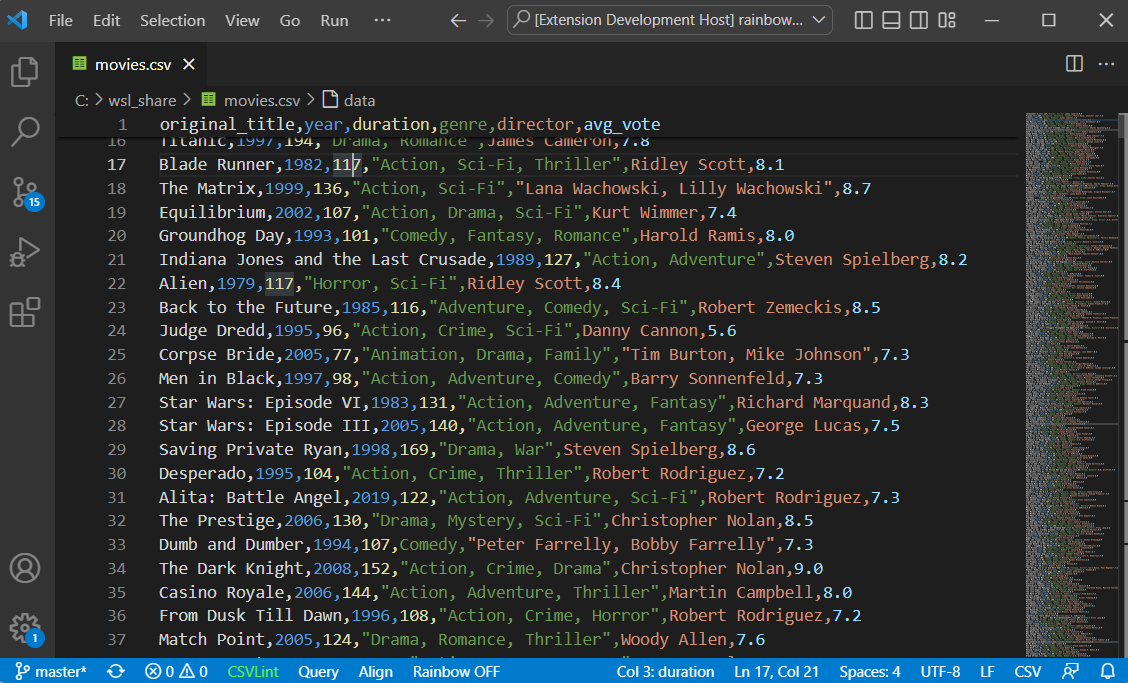

Rainbow CSV is an extension for VSCode that makes working with CSV fields in that editor a lot more bearable.

Not only, as you’d guess from its name, does it colour code things - but you can also run pseudo-SQL commands against the file’s contents to get some quick answers right there and then. Use the RBQL command in VSCode to do that.

Syntax is a little bit different to typical SQL, but easy to pickup. This for instance counts records of a certain value:

select count(a.customer_id) where a.meets_criteria == 'TRUE'

We unleashed Facebook and Instagram’s algorithms on blank accounts. They served up sexism and misogyny

(From The Guardian)

Another in a series of experiments (of admittedly varying levels of rigour) that show the tendency of social media networks to push young men towards misogynistic, sexist or even radicalising content as a default.

Australians are now immersed in this river of complete garbage on Facebook.

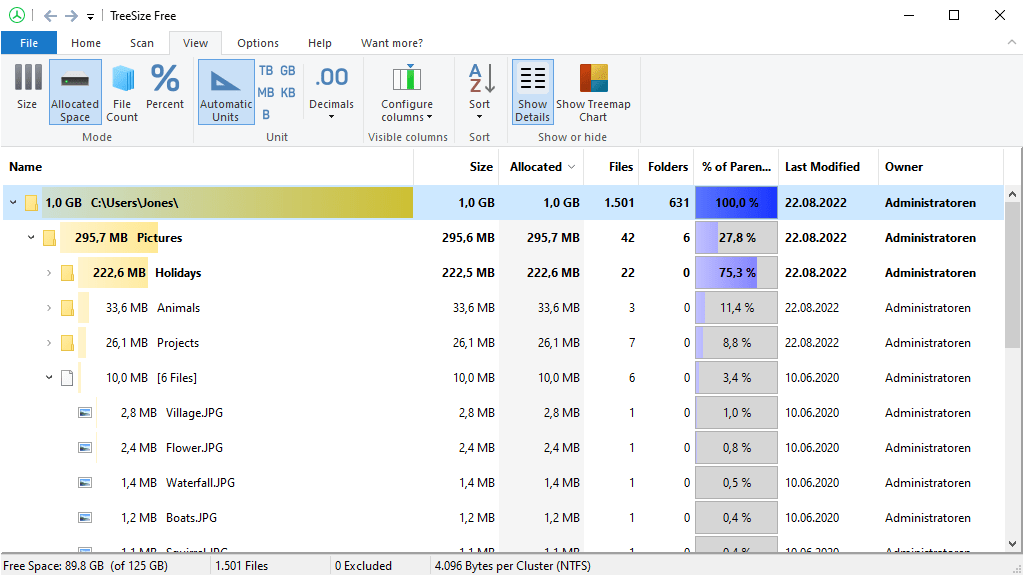

JAM Software’s TreeSize app is a handy Windows utility to quickly visualise which of your files or folders are taking up large amounts of your disk in various ways.

There’s paid versions that have extra fancy options - automation, duplicate finder, breakdowns and so on. But if you just want to know where all your space has gone, the free one works fine. It’s available in a portable edition too.

Generative AI Is Totally Shameless. I Want to Be It

Paul Ford writes entertainingly about generative AI as being a shameless technology, for better or worse.

But what chance did it ever have when its creators and owners also lack that quality?

Hilariously, the makers of ChatGPT—AI people in general—keep trying to teach these systems shame, in the form of special preambles, rules, guidance…

…

But the current crop of AI leadership is absolutely unsuited to this work. They are themselves shameless, grasping at venture capital and talking about how their products will run the world, asking for billions or even trillions in investment. They insist we remake civilization around them and promise it will work out. But how are they going to teach a computer to behave if they can’t?

Think about your actual rather than idealised office when deciding whether to go into work

When thinking about the “should you force employees to come into the office on the basis that it’s a better environment for junior employees to learn and progress in?” debate, Mandy Brown reminds us to not inadvertently used some idealised version of what an office actually is as our yardstick.

The mistake from here is assuming that offices are naturally better at building those kinds of social and supportive structures.

…there’s a kind of mythical office that remote culture is being compared to, a place where everyone is welcomed, where collaboration and support is easy-going and automatic, where everyone is always whiteboarding or talking in the hallways.

It’s kind of astonishing to see how much this presumed office utopia has become implicit, given we have literal decades of satire about offices as locales of poorly lit, soul-sucking, isolated work, where you are more likely to be abused by your boss than sponsored by them.

It feels to me like a good number of cognitive errors can be avoided by thinking hard about what the appropriate - usually meaning realistic - baseline to compare something to actually is.

An example from our recent past:

Don’t compare any potential harms of “getting a Covid vaccination” against the potential harms of “not getting a Covid vaccination and everything else about your life remains the same”. However miniscule the risk of getting a Covid vaccination is - and for the avoidance of doubt it appeared to be extremely low for the vast majority of people - it’ll always come out worse in that comparison.

Instead a much more appropriate comparison is to consider any risks of “getting a Covid vaccination and less likely to thus get Covid” against the risks of “not getting a Covid vaccination and your increased likelihood of then contracting and/or transmitting Covid”.

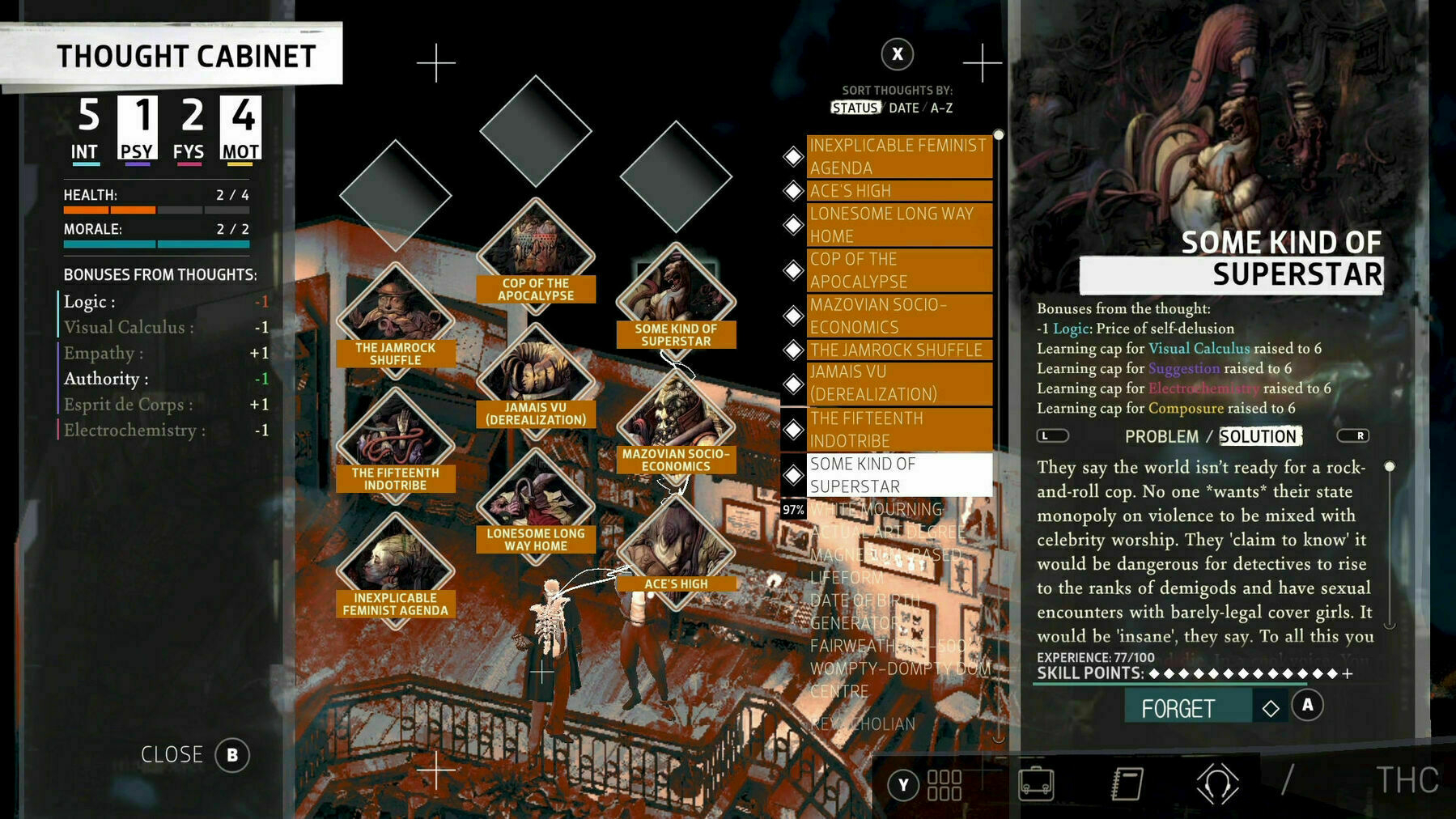

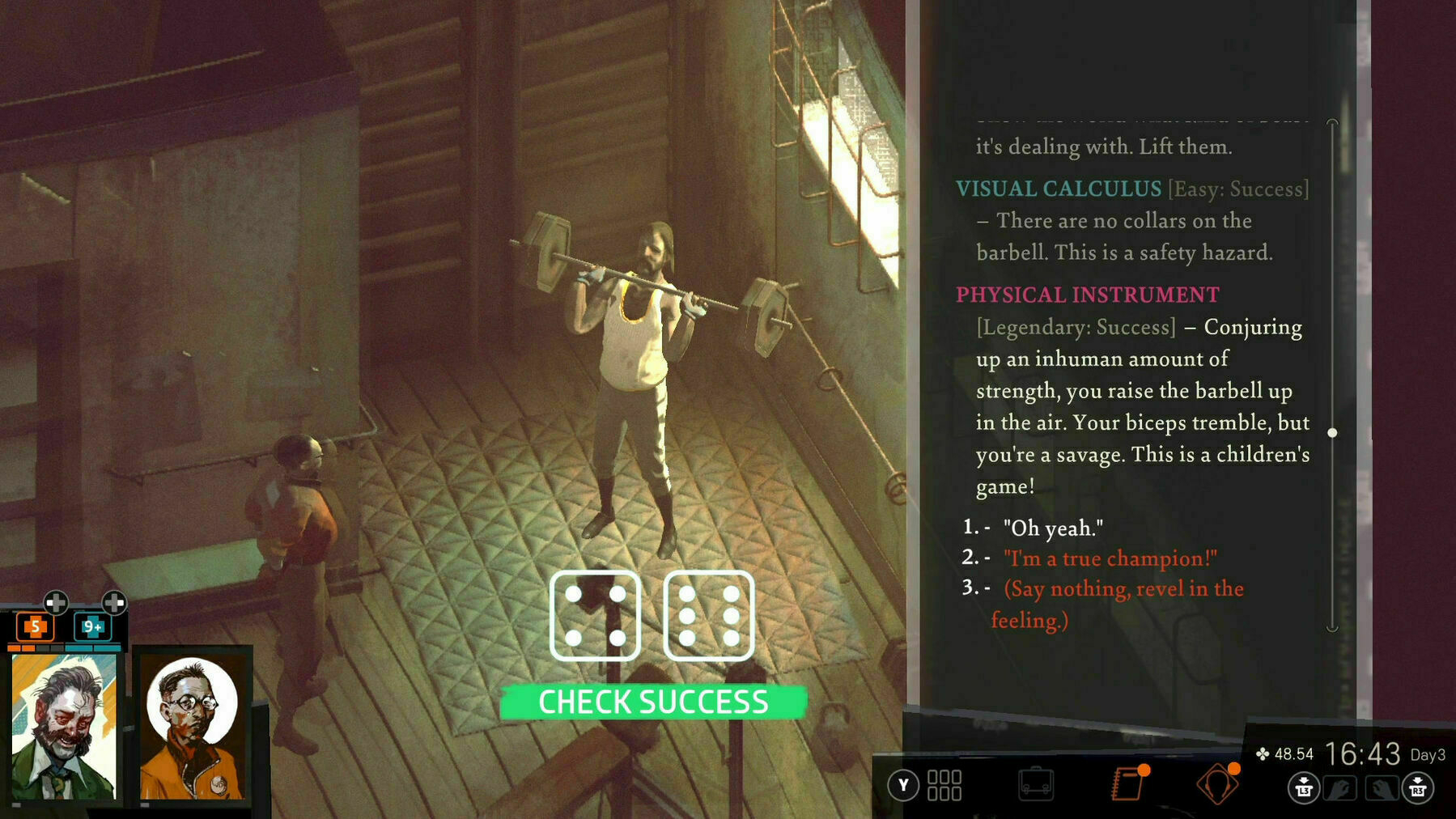

Disco Elysium is one of the most atmospheric, most unique, games I've played

🎮 Played Disco Elysium - The Final Cut.

This was the first time I’d played a game quite like this, if indeed there are all that many games quite like this. It was quite an experience.

Set in Revachol, a somewhat failing post-communist state, you wake up in a hotel room with a debilitating hangover and no memory of, well, very much at all. Some might say it’s therefore quite an accurate simulation of parts of some of our real lives.

(Please note that all the screenshots I’m sharing here are from RPGfan.com - I was far too engaged to remember to take my own.)

Slowly, as you point-and-click your way around your new locale, you find ways to piece together what happened the previous night, and indeed some of the previous nights of your life. It transpires that you’re a detective who is there to solve a murder. Much of this is done via talking to other people, many of whom are less than friendly - particularly those who are in reality running the town through tactics of intimidation.

There is an incredible amount of reading to be done. There over a million words worth of text all in all, although in the deluxe version of the game - “The Final Cut” - it’s all voice-acted out as well if you prefer to listen than read. Apparently a million words is like reading The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit twice through. But, don’t panic, you won’t end up needing to read them all. In fact I doubt you’d even have the option to come close to doing so in a single playthrough even if you wanted to.

So the dialogues are lengthy. But they’re also meaningful. I’ve only played it through once, but your choices of how to respond at least appear to make a real difference to how people treat you later in the game, what opportunities are available to you and, I suspect, the ending.

I soon learned the error of my ways in following that classic RPG-style tactic of mindlessly working my way through every single dialogue option, saying everything the game allowed me to say in the hope the responses would provide clues. That doesn’t work well in the world of Revachol any more than it would in real life. So I started taking my choices more seriously, in order to further the in estimation but also to manage my own (character’s) brain.

“Brain management” is a big part of how you develop your character in this game. Firstly, your survival depends on you managing to sustain both your physical and mental health. At first I found my character losing all motivation for life, let alone detective work, which ended up with me living homeless, under a bridge, rarely sober. That’s the end of the game if you’re not a little careful. Luckily you can save your game pretty much whenever you want so I didn’t have to start all the way over.

You can temporarily boost your physical or mental resilience in an emergency via taking recreational drugs, if you have any and don’t object to doing so - although if your police partner is there they are not the sort of person who’s impressed by such behaviour. And there will be a price to pay in some other aspect of your wellbeing.

For a more permanent form of self-development, you earn points as you progress through the game which you can channel into the development of your brain and body. There are 24 attributes such that fit under 4 categories - intellect, psyche, physique and motorics - that you can elect to improve depending on how you wish to develop your character. Some examples: logic, drama, empathy, pain threshold, reaction speed. Each attribute has various available skill levels.

Your brain state may then influence the choices you can make during dialogue, how other people react to you, how successful you in any actions you choose to make or even what actions or side-quests are available to you - after all you can’t dig into a clue if you never noticed it in the first place.

Your starting set of attributes is dependent on which archetype you choose for your character pre-game. You can opt for a physically strong brawny detective, one with high emotional intelligence or a Sherlock Holmes style character with a high IQ sort of setup.

Another way in which your brain is relevant comes via the mechanism of thoughts. Throughout the game you’ll pick up semblances of ideas. You can choose to dwell on these thoughts, to research them, to “do your own research” as it were. But, like reality, you can only focus on a few at any given time, even when you get over the immediate anguish of your hangover.

These thoughts have quite abstract names “Anti object task force”, “Rigorous self-critique”, “The Jamrock shuffle”, so you never quite know for sure how thinking these thoughts is going to affect you. Some will improve your abilities. Some might make you worse at something. Others are neutral. This seems an accurate reflection of the risks of Googling too hard on some topics in the real world.

Reading books can also have an effect. The final main modifier to your abilities come from your decisions around what to wear. Your wardrobe grows over time as you find or otherwise acquire a large range of outfits each of which can influence your abilities a little.

There’s a lot going on here, but, at least in my experience, little to panic about. I certainly didn’t make the optimum choices but did just fine once I got over my quitting and living under a bridge phase.

The one thing I’d note is that at times the game makes clear that if you follow a certain action or go to a certain place then there’s no going back. To be fair it’s very explicit. But they’re warnings you should heed.

You may well end up with a vast collection of sub-missions as you play, some of which are pertinent to the main quest of murder-solving, others of which are merely interesting diversions. You might do yourself out of the ability to work on a few of the latter type if you disregard such warnings. Unfortunately via being a bit careless around this I failed to complete one of the larger side-quests available in at least the deluxe version of the game - to re-instantiate a successful incarnation of communism (other ideologies are available).

All in all, this was a fascinating and absolutely engaging game of a type I’ve never played before. It was at times slow, bewildering, or frustrating as probability determined I failed to accomplish something I wanted to - some actions' success are dependent on a classic Dungeons-and-Dragons style roll of a dice with the threshold you need to achieve being modified by your character’s personal abilities.

There’s some parts that could be termed tedious or depressing, but I imagine that’s deliberate. It conveyed the atmosphere of the location very well. Indeed this was one of the most successfully atmospheric games I’ve played.

It was, in short, a real, deep and intense experience and one I’m glad I had. A real example of the capability of games to be art. I certainly agree with the many accolades and awards the game won back in the day. I’d be very keen to see if any more examples of this kind of genre and approach are out there.

A Microsoft Powershell command for the brave / foolish-of-heart!

This - I hope:

- looks through all the sub-folders of your present working directory:

- finds all files that have the extension “.rdata”

- that haven’t been updated since 2024-01-01

- and (permanently) deletes them

Get-ChildItem -Recurse -Include *.rdata | Where-Object {$_.LastWriteTime -lt '2024-01-01'} | Remove-Item -Force

Of course you can change the file extensions and dates of relevance to your own needs.

This appears to work for me on the Microsoft Powershell that’s pre-installed with Windows 10. Powershell itself though is available for several other operating systems. Definitely no guarantees from me though that it’s correct and/or won’t destroy your computer.

A bug in Crowdstrike's software breaks large swathes of the world

Large parts of the world are on fire - metaphorically speaking at least, but I’d not rule out a literal interpretation entirely - as a bug in some software from Crowdstrike has inadvertently ruined the operations of various institutions from the worlds of banking, travel, healthcare and beyond. You might not even get paid on time as some payroll processes failed.

What is Crowdstrike? Well, per the BBC:

Crowdstrike is known for producing antivirus software, intended to prevent hackers from causing this very type of disruption.

Whoops.

Apparently they fixed whatever is wrong, but each and every affected device needs to be individually, manually, seen to.

One solution that is apparently worth trying is the same one that fixes almost every other computer issue.

Microsoft is advising clients to try a classic method to get things working - turning it off and on again - in some cases up to 15 times.

We just need the whole world to turn their computers of and on again 15 times.

Crowdstrike last reported having only 24,000 customers. World-disrupting incidents like this just highlight how fragile the way we’ve arranged our technology to operate in can be.

If you ever have a desire to edit MP3 tags without putting your phone down, then Evertag seems worth a look if you’re an iOS user. Supports a wide variety of tags (including album art), cloud services, batch mode, all that good stuff.

Free, with optional paid upgrade.

The compareDF R package seems to be a super convenient way to quickly compare two dataframes to see if they’re the same. Or nearly the same, if you prefer.

It’s often as simple as:

comparison <- compare_df(df_new = my_new_dataframe,

df_old = dataframe_to_compare_to,

group_col = "field_that_identifies_a_unique_row")

No-one seems to sell cheap Linux laptops

It finally happened. My trusty personal laptop died. To be fair I can’t complain; it’s had a good innings, surviving around 11 years. It was a Sony Vaio, which means it long outlasted the part of Sony’s business that manufactured it. It was brought back from the dead once already thanks to a local IT shop, but the fix was impermanent and isn’t worth repeating.

Technology sure has moved on over the decade-plus since I got it. Whilst it could still cope with the basics, it might have gotten too slow to use without frustration after one Windows 10 update or another had I not discovered the virtues of Linux, having installed Linux Mint a while ago.

The performance difference was night and day. No more waiting around for hourglasses to spin or 10 minute boot-up times. And also no more sponsored “recommendations” for apps I’d never want. No more extremely low quality unsolicited “news” in the Start menu.

You can turn much of that off to be fair. But, come on, even the once-sacred, once-pure pastime of many an office worker - sol.exe - was infused with 30 second long video advertisements. Oh, don’t worry, you can still play their solitaire and minesweeper ad-free if you want to. For $20 a year.

For anyone else who has old tech that’s too slow for the more mainstream operating systems, yet correctly detests unnecessary e-waste, I strongly advise you give Linux a go. Despite its reputation, these days if things go smoothly it’s not an immense technical challenge to install, and it’s certainly not hard to use for day-to-day work and play once it is installed. At least if you go for one of the distributions that prioritises ease of use and/or consistency with the computing experiences of other operating systems (Linux Mint being one of those, many other options exist). So you’ve not got a lot to lose if you alternative is throwing the machine away.

Plus there’s no shortage of high quality Linux software to replace your Windows apps. Much of it is free of charge and it’s often extremely easy to install thanks to various pre-installed graphical package managers. And in the case that you do need to run Windows programs, technologies like Wine might get you there.

I soon learned to enjoy Linux more than Windows. I’d set it up as a dual boot system but found that I never actually booted to Windows. Thus I figured that this time I’d go out of my way to buy a laptop designed for and preinstalled with Linux to replace it. I imagined it might even be a cheaper option give there’d be no Windows licensing costs for manufacturers to pay. As much as I’d enjoy some £5000 power-beast it’s just not going to happen right now short of a lottery win.

Turns out I was very wrong, unless I just didn’t search well enough.

Not all that many companies seem to sell new machines with Linux pre-installed on. System76 seem to be amongst the most famous dedicated providers of Linux offerings. But all are substantially above $1000, even without considering any shipping costs to the UK. Juno Computers are another option. Their “entry level” laptops appear to start from £970. Although actually if you click around enough you can find some with older processors that start from £655. StarLabs are another provider, their laptops start at £969.60.

Of the more mainstream computer providers, Dell also do some. They even offer instructions as to how to replace the OS their other laptops come with with Linux which is very cool. But their famous XPS range that has the option of coming with Ubuntu Linux are all above £1000 as far as I can see.

Why so expensive when you can go to some high street shop and get a (admittedly not great) Windows laptop for like £300? To be honest I haven’t done the research to know the answer to this question, which almost certainly has an an actual answer. But heaven forbid I do my homework. So I’m just going to make guesses, that it’s one or more of these potential reasons:

- Linux laptops are not at all popular. It’s a niche market. It’s much more expensive per item to make things fewer people buy.

- Maybe they tend to have better hardware? I guess it’s probably nerd types that tend to want them. Perhaps they’re more likely than average to care about performance.

- If you’re intending to support your customer’s usage of your machine then there would presumably be ongoing costs for that. It must be harder (more expensive) to find agents who can help people solve Linux problems than Windows.

- You’d also have to make sure that drivers etc. for all the hardware you include exist in Linux - and write and maintain them if not.

- Most Windows PC manufacturers and distributors appear to pre-install a load of truly garbage software that you probably don’t want on the system before selling it to you. Clearly this is not for altruistic reasons. Maybe the kickback they get from doing that is so high that it more than makes up for the cost of Windows.

- Perhaps the people that want Linux laptops really want Linux laptops so will pay more? And far be it from any company to not exploit every possible £ of revenue opportunity.

- I’m sure OEMs don’t pay the same for Windows as us mere people do. Perhaps Windows is very cheap for them, or they even receive benefits from Microsoft for ensuring more folk get into their ecosystem.

Nonetheless it seems like a potentially missed opportunity. You can buy (low-performing) Chromebooks for not much more than £100. But I don’t think I could live with a Google operating system, and I’d assume a lack of software choice from the point of those of us who enjoy tinkering, who love options screens with 100 preferences, who occasionally might want to do our own coding.

So, despite my philosophical and in-practice preferences, I’m opting for some sub-£500 Windows machine. In any case, there’s always the option to replace Windows with Linux, which I can totally see myself doing in short order. But I guess I will experiment with Windows 11 for a bit first given I’ve never used it. Maybe I’ll be pleasantly surprised.

That decision does mean I’ll probably want to dedicate some time to reading and acting on a ton of articles like ‘How to disable annoying ads on Windows 11’ and “How to remove bloatware from your new PC” to try and minimise the semi-spyware and advertising networks that apparently infuse Microsoft’s latest creation, an apparently ever more enshittifying iteration.

Ads in the Start menu, in File Explorer, maybe even in Settings for crying out loud - although perhaps fair to note that most of the latter ads are likely for Microsoft services that are supposed to improve your experience, such as OneDrive - if you’re willing to pay. In any case, I like Alaina Yee’s take in PC World:

Look, I’m not in marketing, but if an ad causes a seasoned tech journalist to briefly think his PC got infected with malware, maybe your advertising approach needs improving.

404 Media reveals the “Face Fraud” marketplace, wherein for a few dollars you can buy a set of bland photos and videos of an anonymous human other than yourself.

You can then use these to fake your identity in order to get around any identity verification checks of the sort you might find on various online services including cryptocurrency exchanges - “stock models for services specifically designed for fraud”.

To me, worryingly, this seems like a service that could probably be replaced en masse by generative AI sooner or later. After all the website “This Person Does Not Exist” happily spits out one-offs of entirely fake people on demand. An alternative even lets you specify the age, gender and ethnicity you want.

Contra the New Yorker, Christopher Snowdon gives us some reasons to believe that the case isn’t as absurd as it seemed to be at first sight.

Of course as a total outsider there’s no way for me to know who’s right, who’s telling the wholer truth. But perhaps the recent verdict is less obviously wrong than I’d have thought based only on the New Yorker article.

Britain now has MPs aged from 22 to 80

The recent UK election, with its Labour landside, brought a new record for Britain’s youngest serving MP. Sam Carling, a new MP for Labour in North West Cambridgeshire, is 22 years old. This makes him the first MP to be born in the 21st century. This comes after he scraped victory by just 39 votes against a Conservative MP who had held the seat for nearly 20 years and had a majority of 25,983 in the last general election. Impressive stuff.

As wild as that seems when I think back to my own experience of being 22 - which was definitely not compatible with running any part of anything, let alone the country - I’m excited to see how he goes. After all, I usually find that young people make voting decisions I like better.

At the other end of the age spectrum, Sir Roger Gale, from the Conservative party in the constituency of Herne Bay and Sandwich, is currently the oldest MP. He was elected in 1983 - 19 years before Carling was born - and is currently 80 years old.

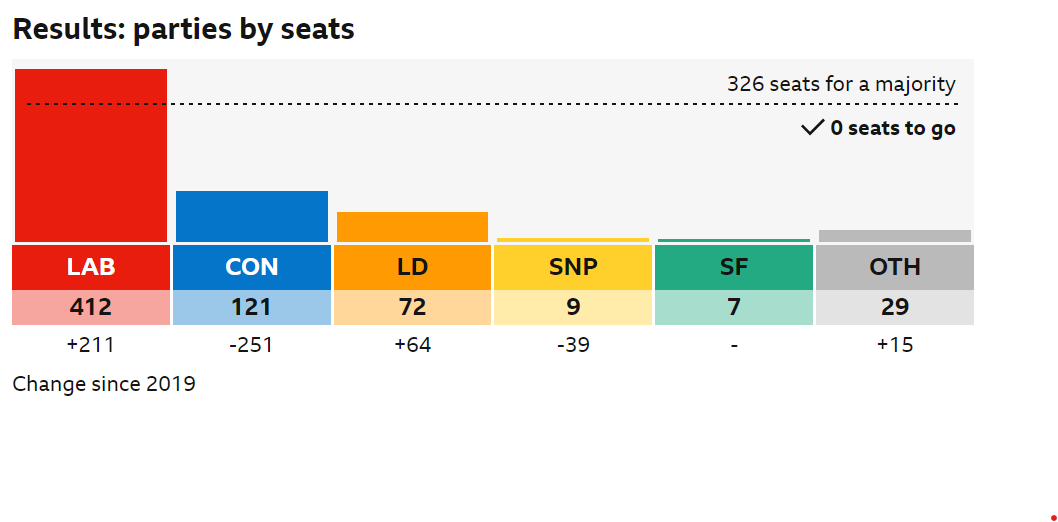

The UK has a new Labour government

The election is over. The UK has a new government, following a landslide victory by Labour.

The results in terms of seats, as per the BBC:

There’s a lot going on under the surface of these numbers, not all of which is reassuring. For one, the “landslide” is a lot more landslidey in terms of seats than votes. But we can surely take a couple of days to celebrate the chance, however small, that we have a new set of people governing us who maybe, just maybe, can improve the lives of our citizens along with what remains of our country.

Whilst he retained his seat our previous PM, Rishi Sunak, has apologised and is going to stand down as Conservative leader.

Other Tory VIPs were less fortunate, losing their seats entirely. That list includes ex PM Liz Truss, who lost her huge 32,988 majority, as well as Grant Shapps, Penny Mordaunt, Alex Chalk and Jacob-Rees Mogg.

Labour lost one potential seat to the excommunicated Jeremy Corbyn.

Unfortunately Reform’s Nigel Farage won his seat - 8th time lucky for him, 1st time unlucky for us - along with 4 other folk from Reform.

The day has come - it's time to go vote in the UK general election

It’s General Election Day today here in the UK. Us UK folk should all leave the house and go and vote, vote vote!

Find your local polling station here. They’re supposed to be open from 7AM through to 10PM. You have to go to the specific one you’ve been assigned to.

Don’t forget to take some photo ID, as foolish as introducing that requirement probably was. What counts as legitimate photo ID is detailed here. It’s the sort of requirement you really have to comply with today, even if you want to campaign against it afterwards.

Also you might as well take your polling card if you have it - but no worries if you lost it, they can look you up there and then in the polling station in order to let you exercise your democratic rights.

If anyone who has a postal vote they forgot to post then you can take those to the polling station in person too (but do take it!).

If you’re too ill / unexpectedly away / have lost all your photo ID then you still have up to 5pm today to apply for an emergency proxy vote if you have someone you can trust to carry out your vote on your behalf. Do that by contacting the electoral services team at your local council ASAP, definitely before 5PM, the details of which can be found via this website.

Nothing is inevitable. And if you’re skeptical that taking action can take a difference, well, not taking an action certainly won’t.

A new Channel 4 documentary asks us 'Can AI steal your vote?'

📺 Watched “Can AI Steal Your Vote?” documentary.

This is a Channel 4 documentary from their Dispatches series whereby they found 12 households who had in common the fact that they claimed to be undecided as to who to vote for in the forthcoming UK general election.

They were then enrolled into an experiment where they were told that they were going to be shown various political content - in the modern style of Facebook posts, Tiktok vids, and the like - on a new social network for an experiment that was designed to test their reactions to political content that might be shown during the election campaign.

Of course the twist, which wasn’t revealed to the participants until after the fact, is that some of this content (hopefully) isn’t actually going to be shown. Because it was AI-generated deepfakes that the show’s creators had come up with.

Typically these deepfakes consisted of video or audio based on real footage or recordings, but altered so that the person concerned - Sunak or Starmer - appeared to be saying something that they never did. Subsequent comments or misleading posts from fake social media users also appeared the timeline.

So for instance we see Sunak apparently claiming that he’s going to save the NHS by introducing a £35 fee to see your doctor (not true) and Starmer saying that he’s going to ensure immigrants get top priority with regard to welfare and housing (also not true). There were also supposed leaks where the Prime Ministerial candidates seemed to be caught saying things like that they only tell voters what they want to hear or that they’re cross some nefarious plan or other got leaked.

6 households were exposed to fake content designed to push them towards voting for the Conservatives, and 6 to content designed to encourage them to vote Labour. At the end of the “experiment” they then have the participants (fake) vote in the way that they would now feel inclined to in the real election - Labour or Conservative - in order to see whether there’s evidence that being exposed to the fake content made a difference to their voting.

It’s probably not much of a spoiler to say that - contrary to Betteridge’s Law - this exposure did have a sizeable affect. OK, I don’t think it was the necessarily the most rigorous of experiments, but it was nonetheless pretty compelling to watch, and a fair warning to us all.

It’s not a overly surprising result. So many of us get our information from social media post style output in this form, whose primary intent is usually to influence us. There’s no reason that fake-but-seems real content would affect us any less than actually real content if done well. Particularly when this content has been actively designed by experts to be as influential and manipulative as possible, which is the scenario faced both by the participants here, and potentially us all in the real world. After all it’s good, perhaps even our duty, to seek out information about who we’re voting for, to learn what they stand for, what they’re likely to do to our country. It just doesn’t work out so well when the information that’s available is lies, indistinguishable at first glance from the truth.

So the participants were in no way behaving oddly, stupidly or in a way deserving mockery. At least a few of them did actually question whether the content was real and true at times. Some looked into a couple of the issues concerned - there was no restriction on what other sources participants could consult - and found no other evidence that some of what they’d seen was true, particularly some of the more outlandish supposed footage. At least one of them works in tech and AI as a job. They were all pretty humble about the experience after the fact. But even with all that taken into account, the claim is that the continued and varied exposure to it had some effect.

Perhaps one of the most interesting comments after it was revealed to the participants that much of the content they’d seen was generative AI fakery was as follows:

Participant: ‘I’m still fuming about charging us £35 for an [doctor’s] appointment and it’s not even true.’

Presenter: ‘In a way scarily there’s a bit of you that might sort of remember that and think maybe it is true.’

Participant: ‘Exactly that. It wasn’t so much now we know it’s fake but the anger is real.’

Presenter: ‘You can’t unthink that in a way.’

Participant: ‘That’s right.’

So, despite the fact they now knew what they’d seen wasn’t real, it doesn’t change the fact that they at the time they first saw it they felt powerful emotions - anger, disgust, fury - the memory of which perhaps unconsciously sticks with them. Emotions affect behaviour, and you can’t rewrite the past. I suppose there is some risk of course that even showing the deepfake content on this show - which they frequently do, albeit it’s systematically watermarked as not being real - could have some effect on the rest of us for a similar reason - let alone if out-of-context clips get circulated or manipulated in exactly the way the show warned about.

There wasn’t a great deal about how to avoid falling prey to this stuff. Perhaps because we don’t really know very much about how to defend this potential onslaught. As one of the experts notes, there’s rarely even time to debunk any given falsehood, even if it was felt that that would do all that much good. Recall Brandolini’s law:

The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it.

Which will be ever more the case now uncountable reams of bullshit can be automatically generated by anyone via AI.

So really the main advice was the fairly obvious (but sometimes hard to remember to do) idea that if you see something that makes you feel a certain way or believe something new - and especially if you feel compelled to share it with other people - at least try to double check the source. It’s awkward to say and none are perfect, but some sources do remain inherently more reputable than others. And if only one or two sources are reporting some clearly world-shattering news then you might be extra sceptical that it ever happened. For example, no British newspaper of record is going to forget to mention a complete revolution in, some would say destruction of, the basic principles of how the NHS works

The whole show seems to be freely available on YouTube - legitimately! - so here we go:

Last month Ticketmaster got hacked by a group known as ShinyHunters, the same group that previously stole data containing details of 70 million AT&T customers.

They got their hands on the personal details of 560 million Ticketmaster customers, with the intention of selling the purloined data onwards for half a million dollars. Apparently the information included at least partial credit card numbers and ticket sales.

No-one, nothing, is safe out there. I guess we all have to operate on the basis of if we enter our data anywhere online then there’s a non-zero chance it’ll be expropriated by bad actors at some point.

From The BBC:

France’s far right is in pole position after the first round of parliamentary elections that confirmed their dominance in French politics and brought them to the gates of power.

Sadly Macron’s absolutely bizarre decision to unnecessarily call an election - seemingly on the basis that his opponents seemed to be doing better than he hoped - appears to be panning out exactly as awfully as most sane people I know predicted. It’s a pretty unprecedented situation for France.

Led by Donkeys doing some of their usual amazing work via slowly dropping a banner featuring an overexcited Vladimir Putin from the ceiling as Reform leader Nigel Farage was in the middle of extolling his usual brand of tripe.

This of course is in large part a reference to Farage’s recent comments that somehow it’s the EU and NATO’s fault that Russia unilaterally attacked Ukraine.

Microsoft accidentally leaks some of the source code behind their PlayReady DRM software.

The technicalities are beyond me, but let’s hope this helps some tech wizard figure out how to remove this particular example of the software scourge known as Digital Rights Management, so that we can permanently store and play any digital content we purchased where and when we want to without so much risk it’ll all vanish some day.

New scandal dropped: The Conservative officials who bet on the election date based on inside knowledge

Several Conservative party candidates and officials are in trouble for, perhaps in a desperate measure to get rich before they lose their jobs on July 4th, by betting on the date of the general election using their insider knowledge before the public announcement was made. This is of course illegal, potentially something you could even go to prison for.

Right now there are at least 6 named Conservative candidates and officials being investigated:

- Craig Williams, the Prime Minister’s parliamentary aide.

- Laura Saunders, Conservative candidate (who is married to the Conservative’s directory of campaigning).

- Tony Lee, Conservative Party director of campaigning

- Nick Mason, the Conservative Party’s chief data officer.

- Russell George, the Welsh Conservative member of the Senedd

Up to 6 police officers are apparently also being looked on for the same matter.

Showing their ability to never totally come out of someone else’s scandal unscathed, there’s also a Labour candidate, Kevin Craig, who is being investigated for better on the Conservatives to win his constituency. I suppose he might have gotten reasonable odds on that given the landslide in the other direction that’s currently expected (at least at a nationwide level, I haven’t checked out his area in particular).

So another day, another (mostly) Tory scandal. It’s not like it was even for serious money. We’re generally talking about bets in the order of £100. Apparently bookies will typically only take fairly small bets on this sort of thing as it’s a fairly small market that they’re less confident that they have an edge over punters than in the case of sports.

It’s very possible more names might come out soon. Newsnight reported that up to 15 Conservative candidates and officials are being looked into by the Gambling Commission. George Osborne has said that around 40 people in total would have been aware of the election date in advance