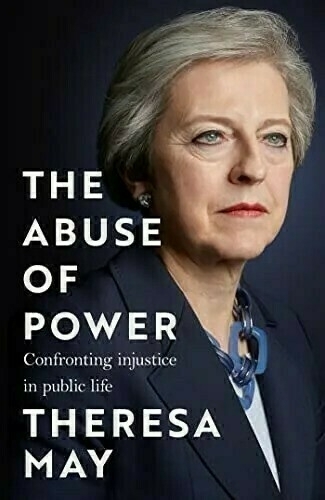

📚 Finished reading The Abuse of Power by Theresa May.

It may, astonishingly, be four Prime Ministers ago, but British folk might still vaguely remember the tenure of PM Theresa May. If not, maybe such trigger-words as “Article 50” or “Hostile Environment” will bring her back to memory. RIP her tenure which somehow only ended 5 years ago despite the number of, umm, “leaders”, we’ve had since then.

Anyway, she wrote a book. Not an autobiography, or at least not a conventional one. It’s a book about some of the various abuses of power she encountered in her political career; the events concerned, a theory of why they happened and how we can stop them happening.

How should we define an abuse of power? She goes with the definition of any occasion when the abusers concerned:

…chose not to use their power in the interests of the powerless, but rather to serve themselves or to protect the institution to which they belonged

The stakes are not low. As she rightly claimed, by those in charge doing otherwise:

…lives have been damaged and sometimes destroyed.

She provides plenty of important examples of exactly that. Seeing the chapter titles might convey some idea of what kind of abuses of power we’re discussing, so I’ll list them below.

She divides the bulk of the case studies up into three sections.

The first concerns inappropriate exertions within the British political sphere - “Power and politics”. The chapters in this section are as follows. The ramblings after the hyphens are my additions:

- Parliamentary abuse - abuse of procedure, people, trust and the like.

- Brexit - no, not its existence or circumstances in which the vote took place, of course not. She’s very much “will of the people” and all that bunkum. Rather the chapter more focussed on any efforts to alter its implementation from her personal vision of what would work well as being abuses, whether from the Remainer or Extreme Brexiteer side. Somewhat remarkably, her take basically seems to boil down to that anyone that disagreed with her must be putting their own interests over the national interest.

- Social media - really as an enabler. Not doing more to remove offensive posts and vicious commentators an example of an abuse of power in her view. I can imagine many people who would find that open to debate.

The second batch of power abuses are considered to be topics of “Social injustice”. These seem more straightforwardly defined and, I hope, less debatable.

- Hillsborough - the 1989 football stadium disaster where people died as a result of being crushed in a crowd.

- Primodos - a hormone based pregnancy test from the 1960s-70s that turned out to be associated with later severe birth defects.

- Grenfell - the 2017 fire that broke out a block of flats that led substantially more than 100 deaths and injuries.

- Child sexual abuse

- Rotherham - by which she means more of the previous topic, but this time the specific cases that took place at the hands of “grooming gangs” in Rotherham from the 1980s up to the 2010s

- Stop and Search - as carried out by the British police.

- Daniel Morgan - the investigation into the murder of a private investigator of that name.

- Windrush - the starting-2018 scandal whereby immigrant British citizens from the Windrush generation, many of whom had come from Britain’s at-the-time colonies to mainland Britain at the invitation of the government in order to help rebuild the country after the second world war, were wrongly punished, including in some cases even being deported from the UK, supposedly because they could not provide evidence that they should be in Britain.

- Modern Slavery

Finally, we move back to more explicit politics - although politics are of course pervasive in all the mentioned abuses so the division might be a little artificial. But this time the geographic scope is wider - “The International Scene”

- Power on the World Stage

- The Salisbury Poisonings - in which UK residents Sergei and Yulia Skripal were poisoned by a nerve agent called Novichok (almost certainly?) at the hands of Russian state assassins.

- Afghanistan - a lot of this is about the admittedly pretty catastrophic US withdrawal in 2020-2021. Again though, I imagine some people would argue with the framing of it in this.

- Ukraine and Putin - Putin’s ongoing illegal war of aggression against Ukraine, primarily the effort that started in 2022.

These are all important stories that we everyone should know about. Some of them continue to dip in and out of the new cycle today. Others are far more often forgotten, but shouldn’t be. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”, and so on. Although her takes on what exactly the abuse in each situation is can at times may seem a bit inconsistent. I’m not sure that Putin invading Ukraine is really. the same type of thing as Speaker John Bercow - who she appears to loathe, terming him a bully and a liar, uncharacteristically strong words - interpreting certain parliamentary polices a bit differently to how she would.

Ignoring that the the somewhat blatant grudge-bearing for one moment, her diagnosis very reasonably seems to be that what abuses of power have in common are that they tend to include:

- A powerful person, group or institution who prioritises protecting themselves, defending their own existence and good reputation over the needs of those who become victims of abuse correctly and fairly. They do this “because they can”, an oft-repeated phrase in the book.

- And victims who are typically ignored, looked down upon, patronised and just generally not treated at all humanely. This of course means that poorer folk, people of colour, immigrants, and so on are over-represented on the victim side. These people with little power, resources or oftentimes respect from the nation are ripe for sacrifice on the alter of protecting the reputation and position of the supposed Great and and the Good.

These are good, reliable, and all-to-prevalent rules of thumb. It’s just that, to borrow another phrase that is repeatedly used in the book, “all too often” I think one could say she has been in a position of responsibility for the commission of abuses herself.

The book goes out of its way to explicitly say something to the effect of “this isn’t about me making excuses for what I did or trying to avoid responsibility, definitely not” several times - I think it’s even the first line of the back cover. But to be honest it does in part really does come across that way to me, particularly in the abuses of the political domain. Sure, there are nods at apologies for her own misdeeds or bad thought processes, but they read to me as rather lackluster or of a downplaying nature. Perhaps even the sort of thing one says when asked what their weaknesses are in a job interview: “…I have been seen as being too careful…” et al.

On the contrary, she rarely passes up an opportunity to drag Labour and other non-Conservative parties into the fray. She seems to feel a particular enmity for John Bercow. To be fair she isn’t entirely factional; her views of Boris Johnson are clearly not favourable, nor for the No-Deal Brexiteers on the right. Dominic Cummings is also correctly on the naughty list, as is Donald Trump (who these days certain factions of the Conservative party appear to be big fans of).

But rarely does she appear to accept all that much responsibility for her own inevitable part in some of either these ad other abuses. The Windrush scandal, for instance, which most certainly came to fore during her time in high politics, she’s at pains to point out that it could have, should have, been solved by all the other governments that came before her. Especially the Labour ones. After all there have been 27 different home secretaries from 1948 until she took the position. Sure, any one of them could have put measures in place to pre-solve the potential problem, but it wasn’t really until her “hostile environment” administration that it became such a life-destroying issue. I’m not all that amazed Clement Atlee overlooked that possible future 75+ years ago - not of course that his contribution to the absolute lack of welcome and racism some of that generation received should be overlooked.

I felt there was rather scant mention of the time she carefully timed an unnecessary general election - three years before the 2020 expected date - just a year after saying that she would certainly not do such a thing. Why? Well, seemingly her decision was driven by the impression that the polls showed that her party would at that moment in time win unfettered power over all government opposition - and hence let her get her personal vision of Brexit through. That decision backfired, badly). And no mention of her restoring the Conservative whip to a couple of MPs that were under investigation for sexually inappropriate conduct essentially in order to boost the population of MPs that were guaranteed to vote in favour of her in a no-confidence vote.

One review notes that:

May’s book is not, really, about her. It’s a reflection on the failings of others and what led them to make the mistakes they did.

Now to her solution to the abuse of power. It’s mainly that we should recruit politicians and other people that are to be put in positions of power who are simply more dedicated to serving the public rather than reigning down megalomaniac power on them. To “consign the abuse of power to the past” we need to elect politicians who put “the common good above personal interest”.

The solution chapter is itself called “The Answer is Service”. We need leaders who are motivated by serving others, not their own interests For politicians it might mean, for instance, emphasising the Nolan Principles - the first of which specifically refers to serving the interest of the public - during recruitment and throughout their careers. This is all good - who could disagree? - but I feel like we could do with a plan a little more specific, a little more practical, than simply “replace the Bad People with Good People”. After all, the party of Boris Johnson - one of the Bad People - was elected to run country by virtue of a public vote; one with a far more convincing result than the one she takes as reflecting the wholesome, good and true “will of the people” (ugh) when it came to Brexit.

Some less charitable commentators have pointed out a slightly different take of her conclusion would be more like “replace all the people I don’t like with copies of me”.

Naturally, we must learn why the abuse of power is so rife in this country. Her diagnosis is simple. Our institutions do not have enough Theresa Mays staffing them.

Whether that’s fair or not, whether she’s right or not, without some kind of undescribed systemic change I don’t really see this as being a pragmatic or actionable solution.