Stop generating, start thinking: Arguments against letting Claude Code et al just blindly do your whole job for you.

Recently I read:

Write about the future you want: “If complaining worked, we would have won the culture war already.”

The enshittification of American hegemony: Countries as platforms.

Is it worth trying to increase your physical activity if you only have time to even think about it on the weekends? New research from Khurshid et al. suggests that yes, it is.

They find that getting at least the recommended 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week provides the same positive association with cardiovascular health whether you do most of your exercising in 1-2 days - their “weekend warrior” classification - or spread it out across the whole week.

…a weekend warrior pattern of physical activity was associated with similarly lower risks of incident atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke compared with more evenly distributed physical activity.

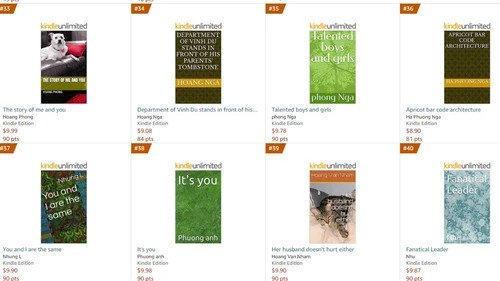

Terrible AI-written books hit the Kindle Unlimited best-seller lists

Another upsetting outcome of the inevitable coming together of the generative AI infocalypse, enshittified subscription service monopolies, misguided algorithmic recommendation systems and the incentives of modern-day capitalism has been achieved. This time this victim is books.

According to Vice, many of the supposedly most popular entries in the Amazon Kindle Unlimited subscription service’s bestseller list recently were in fact fully AI generated nonsense.

A rash of books with similar covers, quite random titles and absolute nonsense inside them apparently hit the top 100 list, at least in categories such as Young Adult romance.

My favourite of the ones Vice reported on has to be the catchily named “Apricot Bar Code Architecture”. The introductory sentence, if you please:

“Black lace pajamas, very short skirt, the most important thing, now this lace pajamas are all wet.”

Now I don’t imagine too many readers made it all the way through these books meaning that whoever put them there probably isn’t raking in too much money per reader. It seems like Kindle Unlimited is paying something like 0.4 US cents per page read, if I understand Chris McMullen’s post correctly. But the fact that they got to the top of the rankings means they’re making some amount of money for someone, likely at the expense of the more traditional actually-makes-sense books.

Because Kindle Unlimited pays authors per page read, not per book read, if you can get 1000 people - real or imaginary - to read the first 5 pages of your effortlessly created clickbait book then you’ll get the same amount of financial reward as someone who can get 10 people to read the entirety of their award-winning 500 page novel - and more than if 5 people who read your 500 page novel valued it so much that throughout their later life they each read it another 10 times each.

I suppose it doesn’t take much for the same folk who set up fake ad-clicking farms to switch to fake book-reading farms.

The new New Conservatives faction has no new ideas

New(ish) Conservative party faction just dropped. Let’s welcome the “New Conservatives” to the party.

They join the National Conservatives and a bunch of other factions such as the European Research Group, Covid Recovery Group, Net Zero Scrutiny Group, Common Sense Group, Blue Collar Conservatism, Northern Research Group and no doubt many others that don’t quite come to the top of my mind right now. One day there will be more factions than politicians if we lucky.

The New Conservatives faction has the extremely non-unique selling point of not liking immigrants. They did manage to come up with a 10 point policy, but every point is a unsubtle rewording of “immigration needs stopped”.

Although if they do ever fully exhaust our patience with anti-immigration cruelty they do have aspirations to move onto being - can you guess? Let’s all say it together: anti-woke.

🥱

I’ll let the i headline speak for itself: ‘They’re dickheads’: New Conservatives group of MPs will cost us the election, Sunak allies say

In particular they appear to be very concerned that the current Prime Minister - who constantly explicitly tells us that lowering immigration, at a time where in some ways the country might actually need immigrants more than ever even for purely selfish reasons, is one of his top priorities at basically any cost - even the cost of breaking international law - should think about adding lowering immigration as one of his priorities. How efficient they are to have achieved their goals before they even existed.

There’s a fun interview on the July 3rd episode of The News Agents podcast where the one of the high-ups of this pointless new faction really really tries to wriggle out of agreeing that what he wants to is prevent is even the most cruelly oppressed and tortured women stuck in Afghanistan from seeking asylum in the UK amongst other things, when that actually seems to be the whole point of his tediously unoriginal faction. Add dishonesty to the litany of sins.

Following some big companies such as Samsung banning or putting limits on their employees' use of tools such as ChatGPT, I wrote about some of the risks one takes when using generative AI systems to write code over here.

From the i:

Nigel Farage has criticised the Home Office’s decision to paint over murals of cartoon figures at an asylum centre for lone children, describing it as “a bit mean”.

Good grief. If Nigel Farage thinks your immigration policy is cruel that really should give you cause to question its morality.

But Sunak et al are still sticking to their story that wanting to see Mickey Mouse is a the main driver of the treacherous journey some of the most desperate children in the world make to our shores.

The Prime Minister’s spokesman suggested the decision was designed to “deter” asylum seekers from crossing the Channel as part of the Mr Sunak’s promise to “stop the boats”.

The latest deranged volley in the Conservative Government’s extremely inhumane and extremely ineffective “anti-immigration” policy has arrived.

It turns out that some asylum reception centres have cartoon images on display.

(image from The Guardian)

This is, of course, Too Woke.

From The Independent:

The Immigration Minister said pictures of cartoons and animals must be removed and that staff should make sure they are painted over, as they give an impression of welcoming, which Mr Jenrick didn’t want to show.

The staff, being humans, didn’t want to do this. But it seems like in the end Robert Jenrick got his way.

Presumably the concern is that millions of children are going to willingly risk their lives at great personal cost to themselves and any remaining family that they may or may not have in order to enter a country that is actively hostile to their very existence mainly because they want to see a picture of Mickey Mouse.

I’ve been looking at options for Network Attached Storage recently, to help me be more conscientious about backups, plus eventually reduce my dependence on various big tech cloud services.

For leaning about the Synology side of things I’m finding SpaceRex’s Youtube channel quite informative.

Conservatives only like law and order when it suits their interests

Frank Wilhoit succinctly encapsulates how at least a subset of conservatives - I suppose he would say all conservatives - appear to think:

Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit:

There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.

This may feel contrary to the classic, now feeling extremely old-fashioned, idea that conservative politics tends towards the politics of law and order.

That sentiment was never straightforward to interpret. There is more to law and order than proudly caging the largest number of people you could possibly justify in an entirely inadequate prison system. But in Wilhoit’s telling it presumably can’t really ever be the case. At least not whilst the law purports to be something that applies equally to all people.

At any moment in time the conservative parties and surrounding movement might look to be extremely pro law and order. But this just means that the law is such that it currently promotes their own interests, usually at the expense of some other group’s interest. Should this stop being the case, so will the avid conservative fandom around the legal process.

These examples are probably so obvious as to not really be worth expressing, but we can see how quickly certain branches of the UK and US conservative movements reacted with wanton disrespect for the legal process and norms as soon as their political heroes - Boris Johnson and Donald Trump - were called to account for their illegal and immoral behaviour.

Johnson was more than happy to explicitly break international law to get his own personally-preferred type of Brexit. In the mean time, some of the conservative British media attempted to brand judges who were insufficiently enthusiastic about that same event as being “enemies of the people”. Trump’s supporters, well, some of them famously engaged in a violent insurrection.

In Wilhoit’s mind then, what would anti-conservatism thinking look like? Simply put, the idea that:

The law cannot protect anyone unless it binds everyone; and it cannot bind anyone unless it protects everyone.

As a sidenote, we’re not talking about Francis Wilhoit the political scientist, but rather Frank Wilhoit the classical music composer who just happens to share the same name.

The US Federal Trade Commission is investigating OpenAI, creators of ChatGPT et al, in order to establish whether they’ve violated consumer protection laws.

The Washington Post shared the Civil Investigative Demand Schedule that’s been sent to OpenAI requesting all sorts of information around how the company deals with the risks associated with their product.

The goal is to determine:

Whether [OpenAI] has (1) engaged in unfair or deceptive privacy or data security practices or (2) engaged in unfair or deceptive practices relating to risks of harm to consumers, including reputational harm…

Learned that you can work in two branches of the same local git repo at once without problems via the git worktree command.

Useful for if you want to quickly fix some code without having to faff around committing or stashing the stuff you were working on

git worktree add <path>automatically creates a new branch whose name is the final component of<path>, which is convenient if you plan to work on a new topic. For instance,git worktree add ../hotfixcreates new branch hotfix and checks it out at path../hotfix. To instead work on an existing branch in a new worktree, usegit worktree add <path> <branch>.

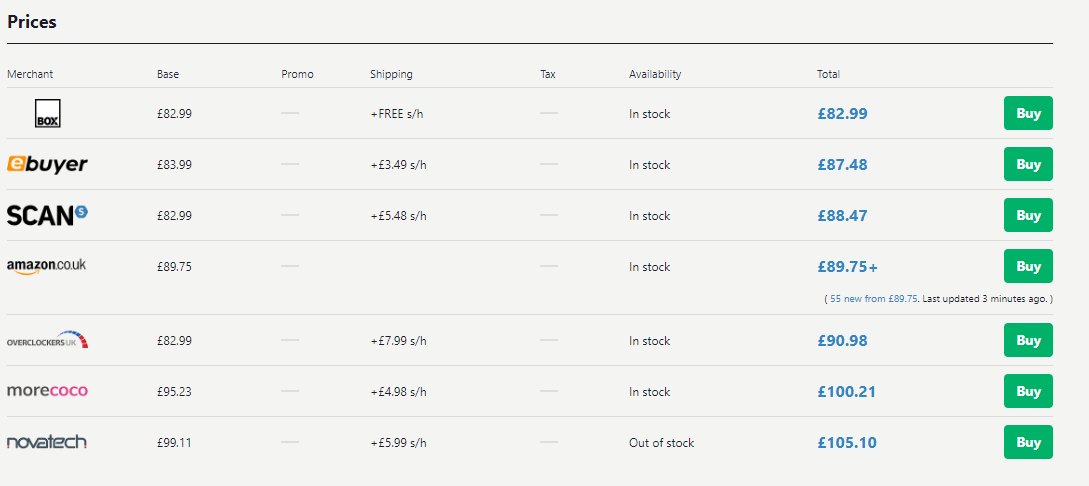

PC Part Picker seems to be a good site for seeing a summary of what, surprise surprise, parts of PCs cost at present. There’s also a price history chart so you can see how it’s varied over time.

The Amazon price history isn’t shown but you could use Camelcamelcamel for that if you needed to.

It’s increasingly apparent that relying on the ability to reliably access or even link to internet content outside of the truly open web is a fool’s errand.

I had problems today building even this little blog, receiving a lot of “Failed to get JSON resource” errors. The culprit turned out to be my use of a Twitter shortcode, which my blog software kindly provides in order to make it easy to embed tweets in their full interactive glory.

To date it’s always been possible for someone who is not logged in to see an individual tweet and for tweets to be embedded on sites. There are sites that almost entirely consist of embedded tweets and some commentary on them, for better or worse (usually worse).

I’m totally guessing, but I’m going to assume that the sudden failure of this method of embedding tweets was a side effect of Musk’s “surprise” change to prevent not-logged in users from seeing anything on Twitter. As well as stopping logged in users, even the rare ones that actually pay for the privilege, from seeing as much as they might want to on Twitter.

This and the ongoing Reddit API fiasco makes me wonder whether Ryan Broderick was right in a recent edition of his newsletter to imply that the only future-proof option for the average user to share even very mainstream content these days is to post screenshots. Doubly so for any content on any site popular enough in in theory be bought by some ideologically incompatible billionaire. How web 1.0.

While trying to track down the actual hyperlink to a post I found a screenshot of on a closed social network I was struck by how on an internet full of closed platforms, broken embeds, and crumbling indexes, the last reliable way to share anything is a screenshot. In other words, the camera roll is, at this point, the real content management system of the social web.

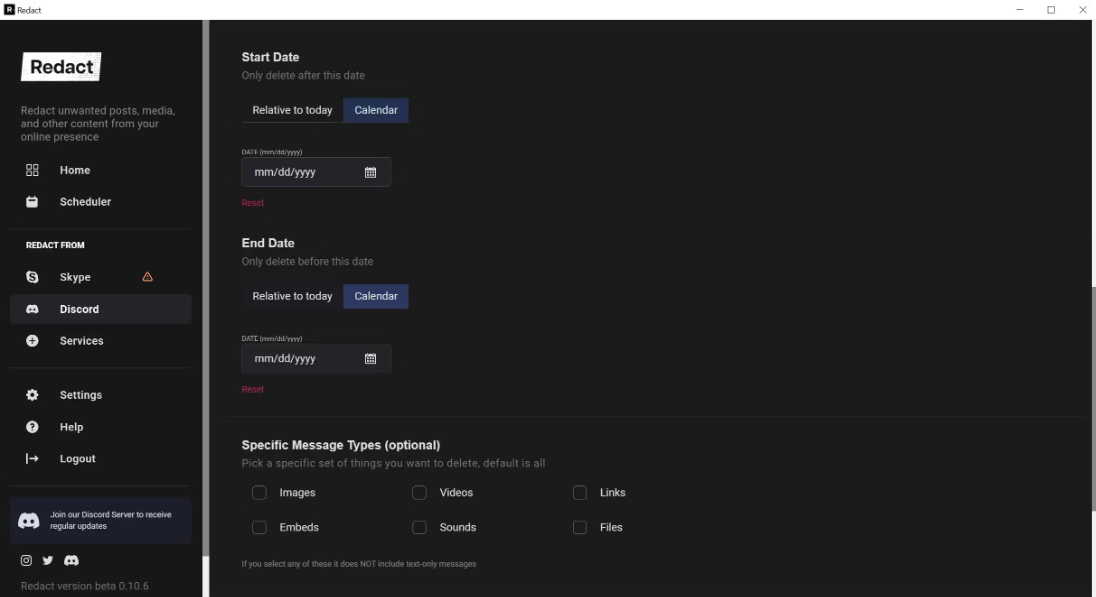

The 'Redact' app lets you delete all those social media posts that you regret writing

For anyone who is sick of either whatever the latest “rich person ruins social network” drama is or the thought of what their own younger self thought was just fine to post to the entire world, the software “Redact” looks like a free and versatile way to remove your posts from a huge variety of services.

It contains filters to allow you to selectively delete things. For example, perhaps you want to delete only Reddit posts you made last year that included the phrase “I love Reddit”, or only the last 7 days of your Twitter DMs. You can also set up a schedule if you want to repeat the delete every so often.

Looking at some of the commentary around the tool it seems like it occasionally stops working for some services. Presumably this is due to changes the social network companies make, including those targeted at stopping tools like this. I suppose you might be infringing certain terms of services if you mass-delete like this in many cases. But whilst the networks don’t spend much effort building their own tools to make it easy to manage and delete your past submissions to their services for obvious reasons this certainly doesn’t feel like a moral crime.

In order to delete things you are going to have to log into your account of the respective services through this software, so you will have to feel OK about trusting that the software isn’t doing bad things. They claim that Redact doesn’t store your info or transmit it anywhere, that their staff have no way of seeing your username of password. But it is closed-source so you can’t check the code directly, so caveat emptor I suppose. I haven’t seen anyone suggesting that anything malicious is going on.

The full list of services it can remove stuff from is long:

- Discord

- Twitch

- YouTube

- Imgur

- Deviantart

- Tumblr

- Microsoft Teams

- Skype

- Slack

- Telegram

- Tinder

- Stack Exchange

- TikTok

- Steam

- Blogger

- Wordpress

- MyAnimeList

- Letterboxd

- Disqus

- Quora

- Github

- Spotify

- IMD

- Gyazo

- Vimeo

- Bumble

- Flickr

- Medium

- Yelp

- Pixiv

- RustleLogs

It’s currently available for Windows, Mac, Linux and Android. Support and other discussions about it mainly seem to happen on their Discord. They also tweet.

In “I wanted to be a teacher but they made me a cop” Adam Mastroianni makes the case that teaching someone is not the same as evaluating someone. The two are often in fact at odds with each other.

He suggests separating the two. Some people become professional teachers, others become professional evaluators. They are after all very different jobs even if we usually try to wedge the latter into the former right now, despite the (over)importance of grades et al. in today’s society.

Doing evaluation on its own would have a few major benefits. First, it would force us to take evaluation seriously.

…

Second, we’d see how hard evaluation is, and maybe we’d do it better.

…

And finally, if we made evaluation its own thing, we’d see how nasty it is, and maybe we’d do less of it.

Twitter’s whims can break other sites too

It’s increasingly apparent that relying on the ability to reliably link to or access internet content outside of the truly open web is something of a fool’s errand.

I had problems last week building even this little blog, receiving a lot of “Failed to get JSON resource” errors. The culprit turned out to be my use of a Twitter shortcode, which the blog software kindly provides in order to make it easy to embed tweets in their full interactive ‘glory’.

To date it’s always been possible for someone who is not logged in to see an individual tweet and for tweets to be embedded on sites. There are sites that almost entirely consist of embedded tweets and some commentary on them, for better or worse (usually worse).

I’m totally guessing, but I’m going to assume that the sudden failure of this method of embedding tweets was a side effect of Musk’s “surprise” change to prevent not-logged in users from seeing anything on Twitter. As well as stopping logged in users, even the rare ones that actually pay for the privilege, from seeing as much as they might want to on Twitter.

This and the ongoing Reddit API fiasco makes me wonder whether Ryan Broderick was right in a recent edition of his newsletter to imply that the only future-proof option for the average user to share even very mainstream content these days is to post screenshots. Doubly so for any content that’s hosted on any site popular enough in in theory be bought by some ideologically incompatible billionaire. So web 1.0.

While trying to track down the actual hyperlink to a post I found a screenshot of on a closed social network I was struck by how on an internet full of closed platforms, broken embeds, and crumbling indexes, the last reliable way to share anything is a screenshot. In other words, the camera roll is, at this point, the real content management system of the social web.

Australia becomes the first country to legalise the use of certain psychedelics in controlled medical environments for the treatment of certain mental health conditions.

…approved psychiatrists can prescribe MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and psilocybin for depression that has resisted other treatments

I’m very pleased the decades of research around this idea has finally produced a policy change.

TIL: The US isn’t the only country to officially celebrate American independence on July 4th. Denmark also does.

Much of that is thanks to Mr Henius, a Danish emigrant to the US, who in 1911 led a group of grateful expats in donating a swathe of Denmark’s land as a ‘place of homecoming for all Danish Americans’. There was a condition:

the park must hold a festival celebrating American Independence Day as a symbol of friendship between the two countries

…which still exists today: US flags, hotdogs and fireworks abound throughout the Rebild Festival.

Here’s a photo from RebildPorten.

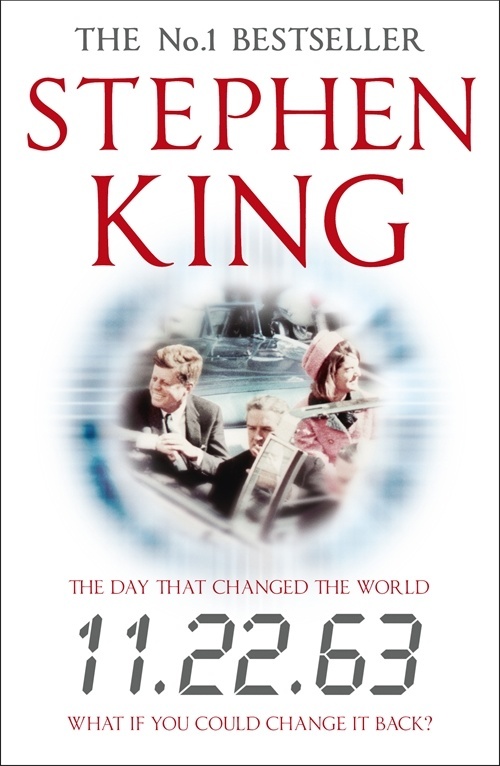

📚 Finished reading 11.22.63 by Stephen King.

Jake Epping, a down-on-his-luck teacher, is recruited by a friend to kill Lee Harvey Oswald before he gets a chance to kill President J. F. Kennedy.

Why? His friend, Al, believes that if JFK had survived then the world would now be a much better place, not least because his practice of politics may have meant that the Vietnam War would never have happened.

Get rid of one wretched waif, buddy, and you could save millions of lives.

And how, given the book is set in relatively modern times, 2011? Well, as luck would have it, Al has discovered a strange portal in a corner of a diner. Walking through it leaves you in the same geographic location in the year 1958.

You can return back to modernity as and when you want. And no matter how long you spent in the past-times world, it’s only 2 minutes later when you come back to 2011. But it might be a totally different 2011 if you did something in the past that had substantial repercussions.

We know that Kennedy was shot in 1963. So Jake has a few years to get accustomed to discretely living in the past, to learn how the world used to work. Unfortunately for him, the past has a way of resisting changes to the original timeline. You might plan to do something that was never done in the 1960s only to be inexplicably diverted, distracted or incapacitated en-route. This tendency is not infallible, the past can change in some ways, but it’s not entirely straightforward.

A further complication is of course the mystery surrounding the JFK assassination. In our world there are plenty of people out there who do not believe Oswald was the real assassin, or at least not the sole person involved. These people include the large majority of Americans in a 2001 poll.

Would killing Oswald in cold blood really stop JFK being assassinated? Especially if not only is there a decent chance that he wasn’t the sole operator involved, but also that tendency of the the past to exert mysterious forces in the direction of recreating its original timeline.

Jake is not a natural murderer. Understandably he wants some certainty that there is some point to conducting this operation before committing such an alien act.

Of course that’s not the only unknown. Sure, Al believes JFK staying alive long would have dramatically improved the world. But would it really? Would there be no cost to pay at all? Few people would feel certain about that, and Jake is no stranger to doubt. So many time travel stories have conveyed to us the idea that altering the past could have intended consequences for the future.

Furthermore, living in any community for several years means you’ll struggle not to build up a lifestyle, habits and human relationships that might be hard to put aside for a small chance of possibly doing something that may or may not make the future a bit better. That’s even if you could navigate your way through an alien world that resists your every attempt to change it so as to be in the right place at the right time to put a potentially huge dent into standard-timeline history.

Well, I’m pleased to say that a mere 800ish pages later you’ll find out what Jake thought and did. Yes, it is a mammoth tome, so long that had it not come with such a strong recommendation I doubt I’d have considered starting it. But the recommendation was a good one. It was over long before I could ever have gotten bored of it.

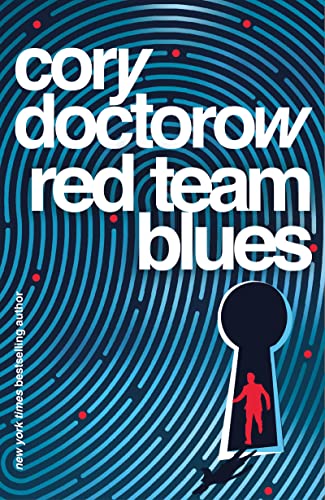

📚 Finished reading Red Team Blues by Cory Doctorow.

In this novel, Martin Hench is an almost-retired forensic accountant who has expert skills in tracking down criminals committing financial-style crimes. We’re talking about the mega-rich and their penchant for moving money around in order to conceal their unnecessary wealth or fund things that should not be funded; money laundering, tax evasion, all that unfortunate stuff.

But before calling it a day he agrees to do one last job for a friend who made a rather questionable decision when designing a new cryptocurrency with very problematic implications. Whilst the rewards on offer are substantial, this final job of course turns out to be a bit more complicated than Hench expected.

The title of the book comes from the concept of red team vs blue team used in several fields including cybersecurity.

A red team is a group that pretends to be an enemy, attempts a physical or digital intrusion against an organization at the direction of that organization, then reports back so that the organization can improve their defenses.

…

There may also be a blue team, a term for cybersecurity employees who are responsible for defending an organization’s networks and computers against attack.

So the red team are the attackers. That’s the position Hench usually found himself in during his career, albeit he wasn’t just pretending to be the enemy.

The blue team are the defenders, in his life this would be the role of the criminals he tracks down as they seek to hide their identities and wealth.

Throughout the book we learn the power imbalance in these roles: the blue team must constantly defend against every possible threat, whereas the red team just needs to be successful one time to achieve their goal.

Personally, I find it hard not to love a book with this amount of computer nerdery in it. I mean, you don’t read sentences like “Danny was old Silicon Valley, a guy who started his own UUCP host so he could help distribute the alt hierarchy” in all that many action thrillers. Some of the technology behind cryptocurrency also features. But don’t let that put you off if you have different tastes. It’s not an academic treatise. You don’t need to have heard of the blockchain in order to appreciate the action.

I even enjoyed the acknowledgements: “thanks to every crypto grifter for giving me such fertile soil to plow”.

This week is London Data Week - ‘Data in the public, for the public’.

Join us at London Data Week for a citywide festival about data to learn, create, discuss, and explore how to use data to shape our city for the better.

I’m not going to be there, but if I was I know I’d be queuing up to experience “a night of edgy, exciting AI and data science-based entertainment with a comedy twist” amongst other offerings.

Providing the greatest educational resources to people who do well on tests isn't the only option

I’m sure Yglesias' post in response to the recent SCOTUS ruling against affirmative action will generate plenty of heated debate. But I was struck by one of the points that’s not really about affirmative action at all, or at least not along the dimensions of identity we mostly commonly think about with this topic.

Part of the benefits of being allowed into an elite US university is that they’re tremendously well resourced. Harvard’s endowment fund was worth an astonishing $53 billion recently. It could provide a huge amount of the best quality educational resources to it’s ~21k students.

But should it?

“…the smarter you are at age 18, the more educational resources you should receive” is not an obviously correct allocation of social resources.

It may be an empirical matter as to what educational distribution model is best for a given society. But first we’d have to define what “best” even means. I’m sure there are many highly conflicting opinions out there on that.

Perhaps today’s division of educational resources is the ideal arrangement for some outcome. But it’s certainly not some kind of natural law that the lion’s share of these resources must go towards the people who already did particularly well on a test when they were a child.

Especially insomuch as the sort of people who do well on school tests and, even moreso, gain access to elite institutions today tend to be those who already had access to the most resources since the day that they were born.

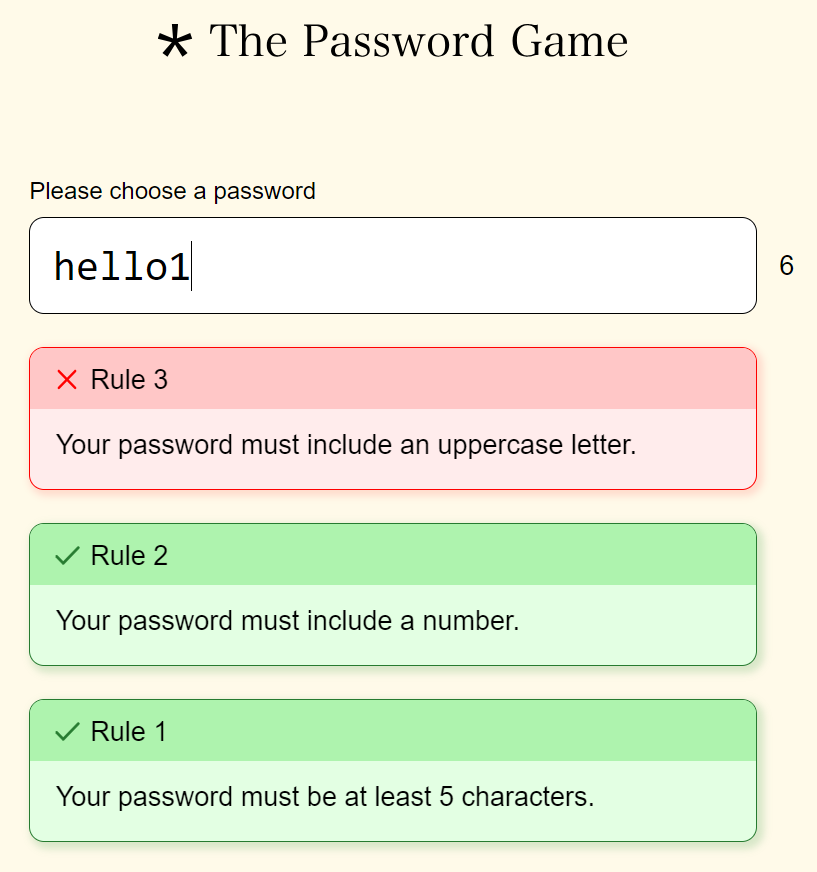

Absolutely obsessed with The Password Game.

All the fun of trying to pick a computer password suitable for one’s corporate accounts, but with…even more fun than this screenshot lets on. Doubt I’ll ever come close to “winning” though.

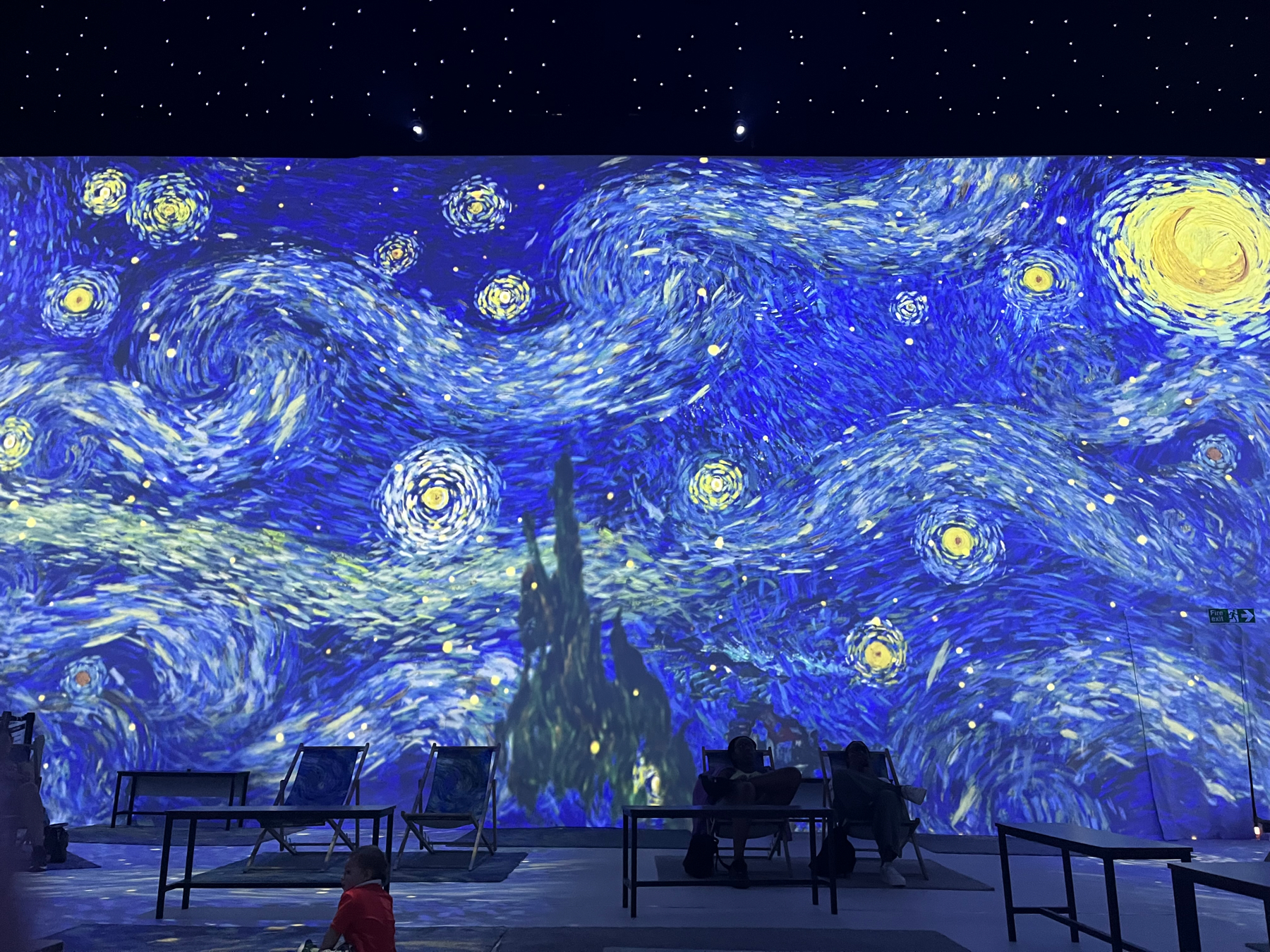

A trip to the Van Gogh Immersive Experience

A couple of weeks ago I went to the Van Gogh Immersive Experience in London.

Here’s the gentleman in question.

Although I’m in general artistically ignorant, I was already a fan particularly of his extremely famous “Starry Night”. The exhibition was kind of short and a bit gimmicky in places, but I do feel like I came away with a deeper appreciation and knowledge of the fellow and a deeper awareness of his art so I’m overall happy enough to have gone.

One such new-to-me fact was that Van Gogh was thought to be colourblind. This may be what is behind his iconic use of colour. Perhaps he literally saw the world differently to most of us do.

Born in 1853, Van Gogh was an even more tortured soul than I had realised. Famously he had psychotic episodes, worsening over his life. These occurred alongside bouts of depression, epilepsy and possibly bipolar disorder. Without the necessary support it could make him hard to live with at times; the well-known cutting his own ear off incident apparently occurred shortly after a huge row with a housemate.

He was fully aware of his condition and the concomitant delusions, checking himself into a psychiatric hospital after the ear event. Even inside such a place he was artistically productive when not entirely incapacitated, producing some of his very widely known pieces of art. Sometimes these were based only on what he could see out of his room’s window, other times by the contents of his dreams: “I dream of painting and then I paint my dream”. Over his lifetime he produced over 2000 artworks.

Eventually he was deemed fit and safe to go return to the outside world. Unfortunately it was too soon. On the last day of his life, July 27th 1890, aged 37, he painted one final picture, Tree Roots, and then, a couple of hours later, shot himself in the chest. It wasn’t an instantaneous death, but two days later he was no longer with us.

Sadly, Van Gogh wasn’t at all well-known or renowned during his life. The excitement around (and incredible valuations of - some have since sold for the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars) his paintings came much later.

The main titular “immersive” part of the exhibition occurs at the end of the show where you get to sit in a deck chair in a big dark room surrounded by animations based on his most famous paintings and quotes, with an appropriate soundtrack for as long as you feel like witnessing the loop.

Pragmatically, it must be said that given the surfeit of excellent and free museums and galleries in London this one is pretty expensive for what it is. That said, I guess the immersive part of it probably isn’t available anywhere else so if you want to see that there’s little choice.

My pro tip if you have some-but-not-infinite cash to burn would be to buy the standard ticket (£18 per adult), not the VIP one (£27.90), even if you want to have a go at the extra VR experience. You can buy entrance to the VR part when you’re there if you want, currently for £5. VIPs can queue-skip, but then again I went on a random Sunday and there was no queue at all. You also don’t get a poster to go home with, but there’s plenty to be had in the gift shop.

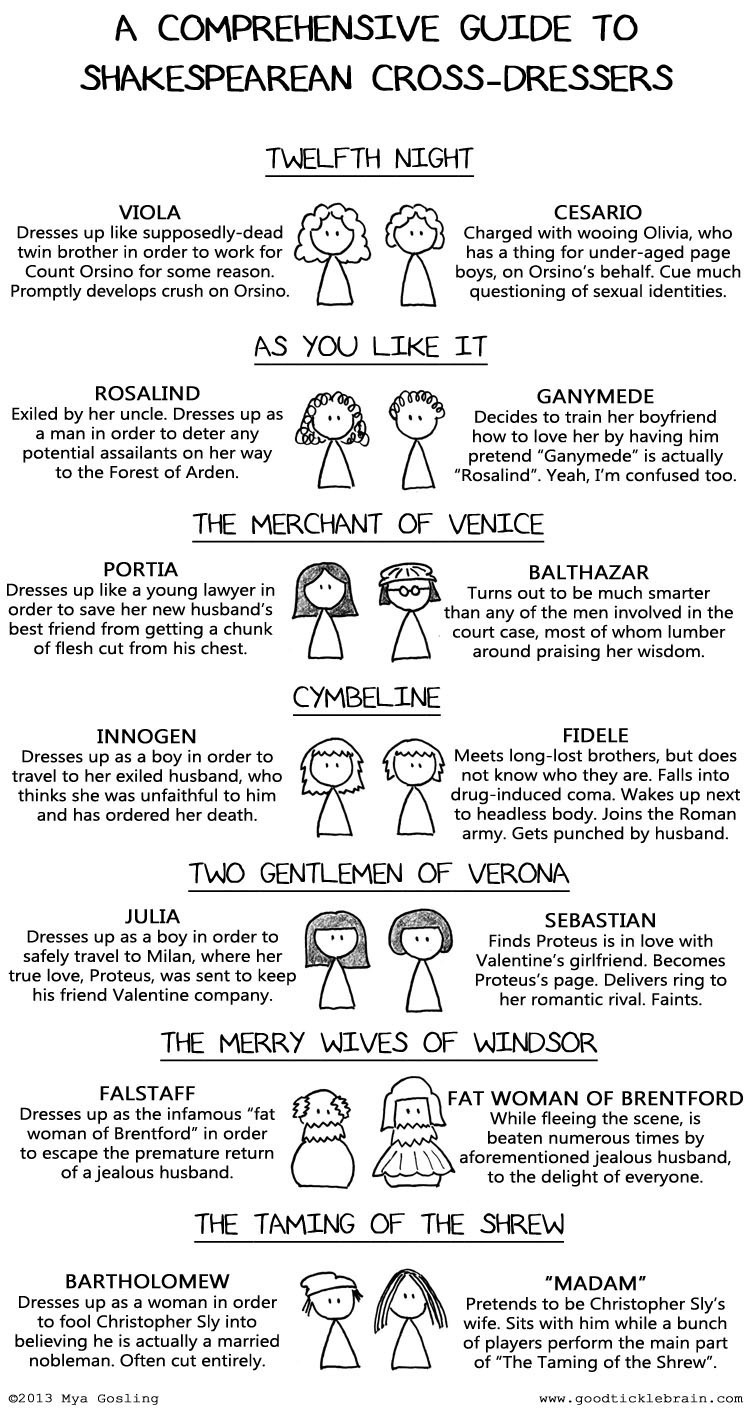

Mya Gosling provides what turns out to be a handy guide to the 7 Shakespeare plays that might accidentally be banned in parts of the US should their ridiculous anti-drag show legislation actually become law.

Good Tickle Brain contains a huge supply of Shakespearean webcomics should you need more.

Huge shock to the system today when I saw what appeared from a distance to be a dead human body on the roadside.

Fortunately upon closer inspection it turned out to be simply something I might characterise as village weirdness. Still rather needs an explanation though.