New Employment Rights Act ‘a huge boost for women in the workplace’: A rare bright spot in the smorgasbord of disappointment from the UK’s Labour government.

Recently I read:

UK must stockpile food in readiness for climate shocks or war, expert warns: ‘The first UK Food Security Report in December 2021 found the country was 54% food self-sufficient’

Latest posts:

🎥 Watched Legally Blonde.

This was the year rewatched the very famous, very popular, feminist comedy film about a pink-obsessed very feminine blonde young lady who takes herself off on a life-changing journey in a somewhat misguided attempt to preserve things as they are. Eventually she realises she’s worth so much more than a trophy wife to an idiot man living a 1950s lifestyle - she’s more than just a pretty face - and, hey, we all learn some sanitised but important bits and pieces about the necessity of feminism along the way.

Not Barbie, that was earlier this year. Instead, 2001’s Legally Blonde. A classic from my formative years. One of the rare films I deigned to watch more than once per lifetime, and might even spring for tickets to the musical in the future if the opportunity should arise.

Our hero is Elle Woods, a young lady who’s into beauty, hair, nails, hanging out with her girlfriends, the colour pink, small dogs and anything else that you could popularly code as “feminine” back in the year 2001.

Her privileged and wealthy boyfriend dumps her. He still likes her enough. but really she’s just a fun time, a bimbo, a silly little girl. Certainly not someone who he can imagine as the serious person that the serious politician he has an ambition should be married to. And you know, male careers come first.

She does not enjoy this decision. Rather than smash up his expensive car though, she decides to follow him to the prestigious only-brainiacs-need-apply Harvard Law School in order to study law and prove she’s a worthwhile and serious person really.

This might be more than a little wince-inducing as the defining motivation for the character - but do remember we’re talking about early 2000s Hollywood-sanitised pop-feminist takes here. Barbie wasn’t perfect and that was more than twenty years later (it was great though). Besides, it’s an important part of the setup. But yep, the film is necessarily something of a product of its times. Don’t expect intersectionality et al. - it’s all pretty young White Heterosexual Lady trying to win her man back stuff. At least at first glance. The feminist focus here is instead more explicitly on the late 90s style priorities of smashing various glass ceilings, girl-bossing it, becoming respected male-dominated places of learning and work. Of changing the world by yourself, not having to be content with hanging off the arm of someone else who does.

Which, spoiler alert, of course she does. But perhaps the most empowering point it makes is that she can do so without changing herself, without donning a mask - refusing to conform to what 1990s (and yes, 2024 for plenty) saw as the image of a fancy lawyer who happens to be female.

Here we see that yes, it is possible to be a young lady who enthusiastically likes “feminine” things and has “feminine” interests and still make waves in spheres of life beyond being pretty and dating eligible bachelors - not that there’s anything wrong or lesser about being interested in those things as well I’m sure Elle would be the first to tell you.

From the New Statesman review:

If its message – that a woman can be smart and enjoy lip gloss simultaneously – does not feel especially radical now, it is worth noting that a generation of millennial women first enjoyed it at the age of ten or 12, when such an idea could be experienced as a revelation.

Thanks to Wikipedia I also learned that the film is based on a novel of the same name by Amanda Brown based on her own experiences of going to Stanford Law School with the same kind of innate preferences for fashion, beauty and the like as our fictional protagonist here.

There’s also a new prequal spinoff TV series called Elle supposedly coming soon, showing her high school lifestyle. But given the second filmic sequel, Legally Blonde 3, was supposed to be released in 2020 and there’s no sign of it yet it’s probably best not to hold one’s breath.

Windows has a keyboard shortcut for opening LinkedIn for some reason

New contender for the least useful Windows keyboard shortcut in existence: Windows key + Ctrl + Alt + Shift + L.

It’s a shortcut to everyone’s favourite thing to do on a computer: visit LinkedIn.

“But why?” you might justifiably ask.

It turns out it’s a mix of two things. Firstly that Microsoft previously tried to make a special new key on keyboards - the Office Key - happen. As far as I know it ended up happening substantially less than even “fetch” did. I’ve never seen one IRL anyway.

As a sidenote: the smiley face key to the right in the above photo from Microsoft was another new key that as far as I know failed to take off - the emoji key. That one I could see a use for in 2024 business settings, particularly if you’re an enthusiastic marketeer. If you don’t have that key on whatever you’re currently sitting in front of, then Windows key + . (i.e. the full-stop key) does the same thing, open the Windows emoji picker.

Anyway, back to the Office Key. Any keyboard shortcuts that would have used the Office key can now be used by the rest of us via Windows + Ctrl + Alt + Shift + whatever. And LinkedIn was one, it being famously the case that the average office worker trawls that site once per hour desperately looking for a new job to escape from their current deskbound prison to.

And secondly that Microsoft bought LinkedIn back in 2016 for $26 billion with the aim to “integrate it with Microsoft’s enterprise software, such as Office 365”. Well, they did successfully integrate it with a key that almost no-one has access to I guess.

The first point means that actually there’s arguably even less useful keyboard shortcuts available if I’m honest. Office Key/ Windows + Ctrl + Alt + Shift + Y for instance opens “yammer.com” which seems to be a kind of Facebook for companies I’ve never heard of called “Viva Engage”. I must admit to visiting LinkedIn more often than Yammer (total for the latter before today: zero times), although I’m not sure it’s been any more productive.

I could see Windows + Ctrl + Alt + Shift + X for “Load Excel” being a bit more useful for me, although by the time I manage to get my hand into the correct shape to reliably hit that combo I probably could have opened it 5 other ways.

The US Food and Drug Administration approved new vaccines for Covid-19 last week. The recommendation from the CDC is that basically everyone goes avail themselves of them, aside from anyone with any specific health conditions that preclude it one assumes.

These vaccines are a lot more effective than the previous set against the latest strains of Covid that are circulating around. These newer variants are causing something of a new wave of Covid cases, albeit one substantially less harmful to most people to what we saw in the early days of the pandemic. But it’s not less harmful to everyone; people are still dying of it, and that’s before we get onto the horror-show of life-altering risks that Long Covid can entail.

Personally I could wish I’d have had one of vaccines a few weeks ago, having gotten quite ill recently - but without travelling through time and space it wasn’t really an option.

Ibrahim Al-Nasser has officially set a new world record for how many video games consoles anyone has ever managed to connect to a TV at the same time. A critical stage in human development of course.

He’s bought enough cables and adaptors to plug in an astonishing 444 “completely different” gaming machines - everything from 1972’s Magnavox Odyssey to the the latest 2023 incarnation of the Playstation 5.

Apparently the Sega Genesis (aka Mega Drive to my fellow country-folk) is his favourite one.

Station Eleven is a highly compelling novel about humanity in the age of a very deadly pandemic

📚 Finished reading Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel.

Imagine Covid but much worse.

This book was released in 2014, several years before the Covid-19 pandemic but is surely a more emotional experience to read after (well, during it). In one or two interviews I saw, the author, very understandably, even seems to feel a little bad that the IRL plague might have proved positive for her in a marketing sense.

Anyway, back in this imaginary world we see a pandemic flu come to the fore - the ‘Georgia Flu’.

But it’s far, far more virulent in terms of spreading and killing than our most recent real life pandemic was. The vast majority of humans are dead within weeks.

Civilisation as we know it collapses in short order.

Travelling via air was one of the first casualties. But within a few years the few folk that survived now live mostly in small, guarded, settlements in a world without basic services such as plumbing or electricity. People are dying of things we’d find inconsequential for the lack of medical resources or technologies.

The book goes forwards and backwards through time, pre and post pandemic , with the most recent sections being set around year 20 of the pandemic if I remember correctly. By that point we have young folk who never knew the pre-pandemic world in place. For this new generation the idea of flying machines and lit up TV screens is pure science fiction.

Governments are long gone. Borders are unguarded. The very concept of countries is alien to those who don’t remember the before-times. In any case there’s no realistic way to travel long distances unless you like very long journeys by horse.

The book follows the lives of various characters before and after the big event. Much of it is centred around the story of a group of musicians and actors known as the ‘Travelling Symphony’.

This is a band of not always merry men and women who travel via horse and cart from settlement to settlement - a far from risk-free endeavour - in order to perform music and theatre to the residents. Why? For them, ‘survival is insufficient’; a quote explicitly borrowed from Star Trek: Voyager.

This is a very engaging, wonderfully written book whose sentimental impact and poignancy has surely only increased now most of us have lived through an admittedly far milder, but still plenty deadly, pandemic of our own.

Whilst dark and upsetting in places - it wasn’t only the good guys who survived, and the collapse of civilisation wouldn’t be pretty either way - the overall message could be taken as one of hope, of the indefatigability of humans and their humanity.

There’s a recent TV show based on the book too which I’m enthusiastic to see at some point.

It’s quite something to have gotten to the point in Britain that a UN committee feels compelled to write reports asking our politicians (amongst other public figures) to be less overtly racist.

The Committee notes the various measures adopted by the State party to address hate crimes. Mowever, it is concerned about the persistence and in some cases sharp increase of hate crimes, hate speech and xenophobic incidents, including racist and xenophobic hate speech in print and broadcasting media as well as the Internet and social media, and by politicians and public figures…

US Democrats borrow a dril tweet - a good excuse to list some faves

Just in case any wayward Americans wanted even more reasons to vote Democrat in the upcoming presidential elections - although “we’re not Trump” should really be sufficient to be fair - it seems like the Dem campaign co-opted a tweet from none other than world’s best poster dril in service of their campaign.

They went with a screenshot of one of the more famous missives; the now-a-decade-old “I’m not mad” one.

and another thing: im not mad. please dont put in the newspaper that i got mad.

It was of course in reference to the increasingly unhinged performances by their mortal enemy, Trump, at his ramshackle press conferences. Writing that sentence just brought back happy memories of the Four Seasons Total Landscaping.

As far as I’m aware this is the first time that this God of the Posting Age has been immortalised in official campaign material. I hope this means he’s granted a special place in the Library of Congress or something.

Unfortunately, the Dems repeated the mistake of all those embarrassing Republican campaigns who use some famous music only to be told by the artist concerned that they loathe everything the campaign stand for. Dril was not quite as vocally aggressive perhaps, but honestly, Kamala should give him at least the $25 he requested

“I think they should be forced to apologize publicly,” writes @dril, “in an unnecessary and embarrassing display of fealty towards me and my posts, as well as compensate me for the full value of the tweet, which I estimate would be about $25.00.”

Maybe he’d even consider withdrawing his rather feisty post on the subject of the current government’s approach to the Israel/Palestine troubles (but probably not, dril doesn’t seem the kind of guy to be so easily bought in this way).

Given he’s back in the news, it seems as good a time as ever to commermorate some of dril’s finest work. If “x.com” ever does totally vanish that will be perhaps the only part I’d miss. Here is some of that gold dust for posterity.

issuing correction on a previous post of mine, regarding the terror group ISIL. you do not, under any circumstances, “gotta hand it to them”

the wise man bowed his head solemnly and spoke: “theres actually zero difference between good & bad things. you imbecile. you fucking moron”

“This Whole Thing Smacks Of Gender,” i holler as i overturn my uncle’s barbeque grill and turn the 4th of July into the 4th of Shit

Food $200 Data $150 Rent $800 Candles $3,600 Utility $150 someone who is good at the economy please help me budget this. my family is dying

IF THE ZOO BANS ME FOR HOLLERING AT THE ANIMALS I WILL FACE GOD AND WALK BACKWARDS INTO HELL

if your grave doesnt say “rest in peace” on it you are automatically drafted into the skeleton war

it is with a heavy heart that i must announce that the celebs are at it again

awfully bold of you to fly the Good Year blimp on a year that has been extremely bad thus far

drunk driving may kill a lot of people, but it also helps a lot of people get to work on time, so, it;s impossible to say if its bad or no

THERAPIST: your problem is, that youre perfect, and everyone is jealous of your good posts, and that makes you rightfully upset. ME: I agree

DOCTOR: you cant keep doing this to yourself. being The Last True Good Boy online will destroy you. you must stop posting with honor ME: No,

Guns:

the human mind… perhaps the most powerful weapon. second only to the “GUN”

turning a big dial taht says “Racism” on it and constantly looking back at the audience for approval like a contestant on the price is right

i often disagree with DigimonOtis, but his efforts to keep Sharia Law out of the donkey kong 64 wiki are much needed in this wolrd of danger

i hate i t when girls think im proposing whenever i take the knee at them in protest

the worst part of nationalism is having to pretend the flag is really good, like “yeah the country looks exactly like that. they nailed it”

theres a popular nursery rhyme in which the singer claims to be a teapot. this, for many children, is their first experience with “Trolling

Not the world’s smallest violin:

playing the worlds most normal sized violin

in a world where big data threatens to commodify our lives,. telling online surveys that i “Dont know” what pringles are constitutes Heroism

im the only guy who knows how to call out the bull shit of society the smart way. and against all odds i do it for free

Another one with potential to victimise the Trump campaign with:

“im not owned! im not owned!!”, i continue to insist as i slowly shrink and transform into a corn cob

ME: please show me the posts in the order that they were made COMPUTER: thats too hard. heres some tweets i think are good. Do you like this

But don’t write to him:

let me be very clear: i would rather attend a Pig’s wedding than attempt to sift through the dumpster you people have made out of my dm box,

the pursuit of having trhe nicest opinions online… is the only thing that separates us from the god damn animals. the sole reason we exist

Honestly, so many gems. None of them really possible to explain to anyone who isn’t immediately bowled over by their beauty

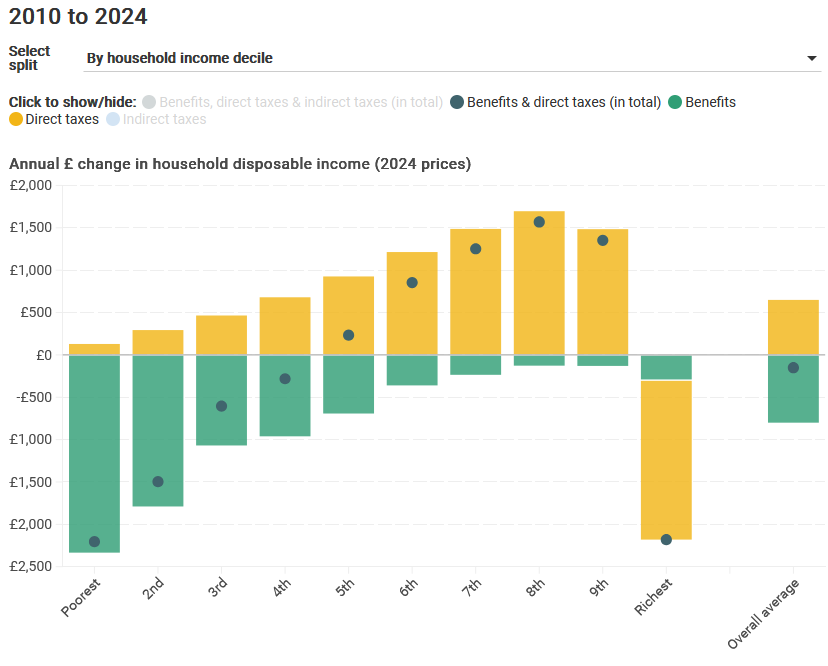

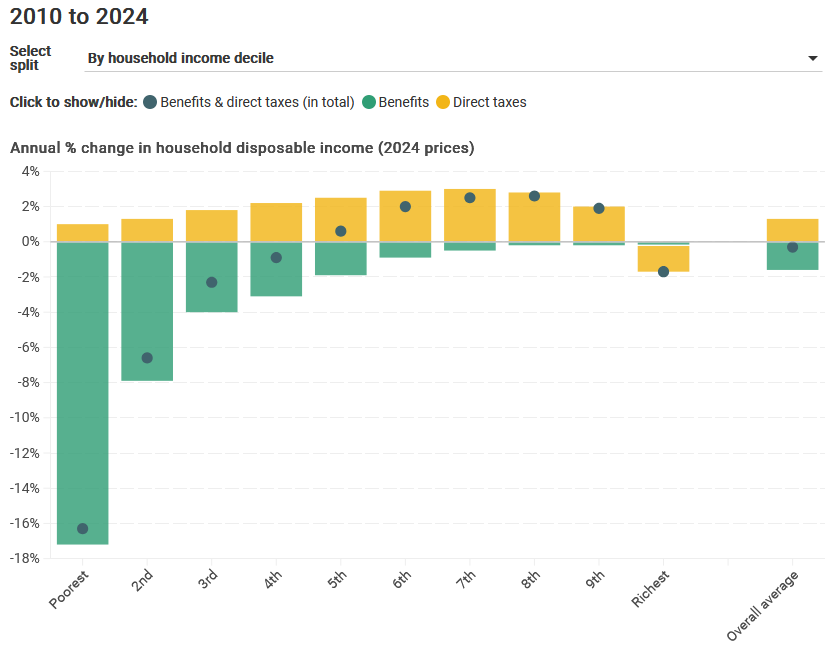

The IFS's interactive 'impact of tax and benefit changes' tool shows the cruel impact of the post-2010 tax and benefit changes

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has released a handy interactive tool that lets you analyse how all the tax and benefit changes since 2010 - the year the Conservatives were elected into government under David Cameron - have impacted the disposable incomes households have at their disposal.

You can segment the chart in various ways including by household income, family type, having children and so on.

It may be a fairly harrowing experience for anyone who hasn’t been following the impacts to date. Its default setup, showing impact of changes to benefits and direct taxes since 2010 shows that the people with the lowest incomes suffered the most. By far.

The general pattern is people with higher incomes were more rewarded by the changes. The rich get richer, the poor suffer more and more.

The exception is the top decile by income who did lose disposable income - equivalent to £2180 per year since 2010. That might sound a lot, but it’s less even in absolute terms that the £2205 that the poorest decile lost out each year.

And because people with the highest incomes have…well…higher incomes to start off with - higher by an order of magnitude on average - in percentage terms the losses by the poorest folk are far, far more dramatic.

Truly sickening. Headlines such as “Absolute poverty: UK sees biggest rise for 30 years” and “Official child poverty statistics: 350,000 more children in poverty and numbers will rise” cannot come as a surprise.

Perhaps the most dramatic, most terrifying, result I found within the chart so far has a relationship to the latter headline above. Whatever cruel untruths the more extreme members of the Conservatives party might like to pretend about adults in poverty, it’s hard for anyone to blame the children. But set the chart to look at working age households who have children and you’ll see that those who had the lowest 10% of incomes in that group apparently lost an astonishing £6,009 per year on average.

It beggars belief to even imagine how they could even begin to cope. I suppose the headlines show that many of them cannot.

Gotta say, currently being in the midst of the outstanding book ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism’ is putting me right off owning any devices labelled ‘smart’.

Although the book is a few years old, it’s super relevant to today’s AI tools too.

Disabling my webcam from being a 'sound, video and game controller' fixed my Windows 11 laptop having no sound

I came across another random fix to an annoying computer problem. When using a Windows 11 laptop it started insisting there were no devices capable of playing sound, even though the computer had its standard speaker, I’d plugged headphones in and so on.

Sometimes the built-in audio trouble-shooter would fix it, but only temporarily.

After some fiddling around I determined it seemed to happen when my webcam was plugged in. It turns out that this isn’t a problem unique to me, but Reddit helped provide an answer.

The solution for me was to open Device Manager. One way to get there is to open the Start menu and, type Device Manager.

Then look for the category of devices in it called “Sound, video and game controllers”. Assuming you find that your webcam is listed there (in my case it was a Logitech C920), right click it and choose to disable it.

After a reboot I had my sound back! And the webcam still appears to work. At least as a video camera which is what I use it for. I suppose any audio functionality it has built into it may not work, but I didn’t test that. Personally I don’t need my webcam playing or recording its own audio.

I’ve no idea if this is a bug with Windows 11, the specific drivers some part of my audio setup or the webcam itself, or what. But whatever the cause, the above fixed it. You can always repeat the above and choose to re-enable the thing you disabled if it doesn’t work out for you.

Is there anything more ‘US politics in 2024’ than this?

While the real Trump-Musk Space on X does not appear to be working, there’s currently a deepfake livestream of the Trump-Musk interview on a fake Tesla channel on YouTube, with 200,000 people watching.

(from Shayan Sardarizadeh)

Especially when it turned out to be a cryptocurrency scam.

So far in 2024, one woman in the UK has allegedly been killed by a man every three days on average. The Guardian tells their stories.

📚 Finished reading Starting & Running a Business All-in-One For Dummies by Colin Barrow. At least the sections of it that seemed relevant to what I wanted to know.

After years of exclusively working for larger organisations, I recently had reason to learn something about how to set up a new business. Having little experience in the area, and with no obvious lead contender in books to learn this stuff from, I felt like a book “for dummies” might be appropriate for me.

It claims to be six books in one. That’s perhaps a stretch - but does give a clue as to how the volume is laid out. These are the titles of the six “books”:

- Laying the groundwork

- Sorting out your finances

- Finding and managing staff

- Keeping on top of your books

- Marketing and advertising your wares

- Growing and improving your business

There is a little repetition between some of the sections, but not a ton.

Having not a lot to compare it to I don’t feel qualified to give a strong verdict on it. My sense it that whilst it doesn’t go in-depth enough in many topics to be all you would need to know in order to optimally succeed, it did provide at least a couple of helpful features:

- It helps those of us who are inexperienced at least know which topics we should be thinking about. For instance, I’m not sure I’d have realised that I should look into the insurance implications of working from home, or that there are so many different organisations out there that may be open to supporting or nurturing small businesses. It also helped me to know what the basic suite of financial reports that folk evaluating a business would be interested in are - even if there’s likely not enough detail enclosed to, for instance, confidently complete a tax return. But it at least reminds you that you will need to complete one!

- It also has plenty of links to further information - mostly websites, and a few phone numbers. Lists of potentially useful organisations, links to free tools and templates, to government resources, to further information from industry bodies and so on. So it’s a also nice collection of “here are some websites you might want to visit before going too far down any unchangeable path”.

The UK far right riots show the days of overt and violent racist behaviour in the UK are far from over

The past few days have made it very clear that anyone who thought the days of the British far right as an effectual and meaningful force was a relic of the past were wrong.

The days of overt racism leading to rabid racist-inspired violence at a level that “matters” (as if any level wouldn’t) have gone nowhere, even whilst people that should know better occasionally try and pretend everything is at least OKish.

Catching up with the news somewhat late, there was a horrific and deadly, attack on a group of children and the people who were supervising their dance class. Three children died and a further group of 10 adults and children were stabbed. It was an appalling act. There are no excuses. The perpetrator is in custody and that can only be a good thing.

Some bright spark on “X” decided to invent the fact that the attack was carried out by a Muslim asylum seeker who had just gotten off - of course - a small boat - naming him and everything. In reality the attacker was born in Wales, but hey, social media gonna social media.

Of course even if that story had been true what came next would have been outrageous. But for it all to be based on a lie just makes it even more sickening somehow.

The event kicked off far-right inspired protests, riots, and abject violence all around the country. Screaming hatred at anyone who didn’t look like Nick Griffin’s idiotic vision of what a “true” Ingerlandder looks like was just the start. Presenting a truly hostile environment beyond even the original vision of the Conservatives was on full display. Petrol bombs were thrown at mosques. Police vans and stations were set alight. Rocks were hurled at Filipino nurses who were on their way to work in a hospital as emergency cover during these riots. Mobs even descended on multiple hotels where they believed asylum seekers were being held in order to burn them alive, all whilst shouting “England, England, England”.

In short, all the things that one might expect to happen in a resentful, racist country which has for years (forever?) been constantly fed inflammatory lies from our mainstream politicians and media, mixed in with the malign influence of present-day social media, about how some of the most desperate people in the world are “invading” our country solely in order to ruin your life specifically. We’ve been somehow convinced that it’s the people with no power, rather than the people that exercise true power over us, that make our lives a struggle. As soon as some perceived - no matter how illogical - “excuse” for individuals of certain views to let out their simmering, violent, racist intentions pops up, this is what we see; egged on by foreign disinformation spread by such luminaries as Elon Musk amongst many others.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds - a newer Star Trek series seemingly modelled on TNG

📺 Watched Star Trek: Strange New Worlds.

I was a huge fan of Star Trek: The Next Generation as a child, and also enjoyed the re-runs of the original series. And with Strange New Worlds they’ve finally produced something kind of similar.

It’s a refreshing change from some of the other recent reincarnations of Star Trek which are often very enjoyable, but more in the vein of trying to be a gritty 12 hour long film with appropriate thriller-style cliff-hangers you need to remember from one episode to the next, if not binging.

So with this one, we’re back to (almost) each episode being its own little story, with a set up, the requisite drama and a resolution all within the hour. What the crew actually gets up to seems also quite similar to the older TNG stuff - exploring, encountering new aliens, facing dilemmas, accidentally travelling through time and dimensions, that kind of thing. There are some storylines that permeate through each series, which was also the case in the old show - but the main drama of the day is a one-and-done thing contained within a single episode for the most part.

There’s occasionally some real cheesy stuff, kind of like some of the newer Doctor Who episodes have. Those episodes I typically don’t love as much, but they make for some variation, and presumably some people do enjoy them. Yes, they even found a way to wedge in a musical episode.

Old-school Trek fans will also recognise at least some of the characters. They are substantially more baby-faced to their previous incarnations due to the series being set in the time period preceding Captain Kirk’s captainship of the Enterprise. Instead it’s Captain Pike, Kirk’s immediate predecessor, in charge of the original version of the Federation’s flagship, the Starship Enterprise.

Serving alongside him we see a couple of old faves - a communications trainee who happens to have the surname Uhura, and Spock, already a science officer, already struggling with his half-Vulcan half-human identity. Turns out future-Captain Kirk (who we do meet, but not as a captain) has a brother, a xenobiologist type, who works for Pike. I understand that people with better memories than me will also recognise some of the other crew, or at least that they were referred to back in the day.

So all in all, similar characters, similar adventures, similar episode structures to the decades-old incarnation of the Trekkie universe. Hard to objectively say how much I enjoyed it for the nostalgia vs how much I’d love it if I was new to the whole thing. But for anyone similarly aged to me who wants something akin to the TNG adventures, definitely go for it.

The tech billionaires who at least used to be ashamed about their support for Trump

Some conspiracies are real. For all the right-wing concern about some loony left shadowy elites trying to control the world and generally being up to no good, I think it’s a few of the mega rich and powerful folk who are clearly on the right - even if they occasionally decide they’re godlike being who operate at levels above such pathetic human ideologies - we might worry about in the immediate term.

A few months ago the Wall Street Journal reported that:

In April, Musk co-hosted a secret dinner of around a dozen business leaders in Los Angeles. The guests included Peltz; venture capitalist Peter Thiel; former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin; and media mogul Rupert Murdoch, chairman emeritus of News Corp, which owns The Wall Street Journal, according to people familiar with the matter.

This took place at David Sacks' massive house. Sacks and Musk worked together back in the early days of Paypal. Sacks is now, of course, yet another Silicon Valley venture capitalist.

Puck adds further names to the guest list- although I’m not certain if this refers to the same event or another similar anti-Biden “secret billionaire dinner party”:

Michael Milken himself was there, in fact, as were billionaires Rupert Murdoch and Peter Thiel. A few government types, including Steven Mnuchin, scored invites. There were also some less politically active titans of industry, such as Uber co-founder and former C.E.O. Travis Kalanick

Why are all these distasteful people taking the time to go party at each other’s houses? Basically in the service of political corruption via wealth.

Back to the WSJ’s reporting:

The discussion at times centered on how attendees could give money to Trump outside of public view.

Essentially, how best to funnel huge amounts of money into defeating the Democrats as a whole, given even America has some limits on this kind of thing. Plus, believe it or not, there was a time that giving millionaires to a uniquely unsuitable and unstable presidential candidate out of at best sheer personal greed, was something a few of even this posse might feel some shame about.

Anyway, the gatherings spread. Real X-Files smoking man stuff.

Peltz and Musk also told Trump of an influence campaign in elite circles that is already under way, in which Musk and his political allies host gatherings of powerful business leaders across the country to try to convince them not to support President Biden’s re-election campaign.

Whilst Puck’s reporting suggested that the gathering they wrote about was supposedly more anti-Democrat than pro-Trump as a person, we do now know that some of those folk are very invested in supporting Trump as a person; in fact as the most qualified person in the whole of the US to exercise increasingly absolute power over its citizenry.

In more recent times, particularly since the assassination attempt on their preferred leader, Donald Trump, the whole shadowy billionaires having secret meetings about corrupting the political process in favour of Trump with their vast wealth has become less of an amateur secret conspiracy and more a very public stating of preferences and pumping of vast sums of money in order to try and buy the election result that they want, alongside currying favour with the famously unreliable but perfectly able-to-be-bribed potential future president that they believe can make all their unhinged dreams come true.

David Sacks went from saying in 2021 that Trump had “disqualified himself from being a candidate at the national level again” to a public endorsement in 2024. Elon Musk and Marc Andreessen are amongst other public supporters and money shovellers.

Musk is one of the larger donors, having recently pledged to donate $45 million a month to a pro-Trump Super PAC (for the non-Americans amongst us, the relevance of a Super PAC here as far as I understand it is that it’s a workaround so very rich people can give way more money to political campaigns than they would technically be allowed to directly). The same PAC is receiving hefty donations from Palantir Technologies co-founder Joe Lonsdale and the Winklevoss twins, who it turns out are now heavily into cryptocurrency.

So what does one get for $45 million? Well, outside of a formal role in Trump’s government, it seems that you probably get to choose who the US Vice President is going to be. Unless it was a perfect coincidence that the day after Musk committed that money Trump announced that his pick was the multi-millionaire JD Vance, who happens to be someone these weird tech billionaires really like.

Despite being famous in the past for having written a book about the travails of being a poor White man in his memoir, which somehow I still haven’t read - Hillbilly Elegy - Vance actually spent many of his earlier years working as a Silicon Valley venture capitalist under the afore-mentioned arch-libertarian Peter Thiel.

In fact the illogically wealthy tech bros like JD Vance so much that mere hours after Trump named him as his VP pick we saw some more of those kind of VCs, Marc Andreessen - someone who has convinced himself that regulating artificial intelligence is Ackchyually “a form of murder”, - and his company’s cofounder Ben Horowitz, publicly express their support for this dangerous fool.

As far as I can tell, substantial motivation for this comes from Trumps likelihood of not getting in the way of whatever the latest cryptocurrency scam they want to run is.

As The American Prospect writes:

…to Musk and Thiel and a growing number of the Valley’s biggest players, any infringement on capitalists’ sovereignty is anathema

JD Vance very much sups from the same cup.

And it certainly seems to be buying them the outcome they want. See for example the extremely bizarre section of the Republican’s 2024 platform whereby they decry any attempts to limit the grift-filled world of cryptocurrency or any attempt to stop AI Hitlers coming to the fore:

Republicans will end Democrats’ unlawful and unAmerican Crypto crackdown and oppose the creation of a Central Bank Digital Currency.

We will defend the right to mine Bitcoin, and ensure every American has the right to self-custody of their Digital Assets, and transact free from Government Surveillance and Control. ….

We will repeal Joe Biden’s dangerous Executive Order that hinders AI Innovation, and imposes Radical Leftwing ideas on the development of this technology.

Sure. it’s written in the style of a particularly unhinged kidnapper sending a ransom note, and maybe the founding fathers didn’t technically list the right to solving sudokus whilst the world burns as a fundamental human right as such, but I’m sure they would have if they weren’t busy with other stuff.

404 Media notes that of course there’s not really any shortage of uncontrolled AI bunkum flying around the world under Biden’s administration. Rather:

…Vance and Trump are not uniquely qualified to support the development of AI. They are simply the Republican nominees, and people at the head of AI companies and venture capital firms are excited about them because historically Republican administrations make them pay less taxes and do whatever they want.

The VP nomination happened even though Vance didn’t really get on well with Trump in the past which would normally disqualify him from taking a seat anywhere near the famously grudge-bearing snowflake who turns on even the people who truly trust him whenever it suits him.

Choice phrases Vance used to describe Trump in the past include “a moral disaster”, “America’s Hitler”, “a total fraud” and “reprehensible”.

But by 2020 this never-Trumper was publicly voting for Trump, whilst arguing that he too at least semi-believes some version of the Big Lie and wouldn’t have certified the 2020 electoral result but rather kept himself busy by firing every single civil servant instead. Very normal. Definitely not weird (or illegal). And in 2024 he’s standing as his best-buddy VP.

The thirst for power at the expense of everything and everyone else is truly a disgusting thing to watch.

📚 Finished reading Titanium Noir by Nick Harkaway.

Sci-fi detective noir, what’s not to love in this genre? It’s set in a world where a very few, very rich, contingent of people have managed to get themselves treated with a new genetic therapy called T7. You know, exactly the kind of thing our current tech billionaires would hoard and indulge in if they knew how to.

Taking that drug, whilst in the short term being a painful experience, essentially resets your physical system to something like your teenage years. You de-age, become healthier, bigger, stronger and so on. You might be 70 years old in chronological terms, but appear and feel like a giant, even God-like, 40 year old. The owner of the company that makes this stuff, Stefan Tonfamecasca, has had a few doses and grown to almost 4 metres tall with an equivalently boosted all-round stature.

In short, the patients who use this therapy become Titans.

Cal Sounder, on the other hand - a standard human - is an independent detective who specialises in consulting on sensitive cases that the police don’t really want to touch. These include cases involving Titans, a subject area that the conventional police are loathe to dig into too deeply not least due to the power structures involved.

Imagine Sounder’s surprise then when he shows up to a supposedly mundane murder scene, as far as that sort of thing could exist, where the victim appeared at first to be a fairly poor, beleaguered, very shy professor. Of course it turns out that the professor was in fact a Titan. But how on earth did such an atypical guy become a Titan? And who could possibly have killed such a giant? Titans, with all their privileges and protections, do not typically end up as murder victims.

That’s for Cal, and the reader, to figure out.

Robert Jenrick, a Conservative MP who has aspirations to lead the party despite apparently being a free-speech-loathing god-hating Nigel Farage fan, seems to think that anyone who says “God is Great” should be immediately arrested.

Well, only if they say it in a language he doesn’t like to be fair - namely it’s the phrase “Allahu Akbar” that he believes should be a crime to utter.

“I thought it was quite wrong that somebody could shout ‘Allahu Akbar’ on the streets of London and not be immediately arrested”

He is of course not suggesting that the exclusively Christian prayers that happen at the start of each sitting of the House of Commons or House of Lords need to go.

In news that chills me to the core, Hazel, a software engineer, has been keeping around 7,500 tabs open on her web browser, Firefox, for the past couple of years.

The Firefox fan tells PCMag in a message that she keeps so many tabs open for nostalgia reasons. “I like to scroll back and see clusters of tabs from months ago—it’s like a trip down memory lane on whatever I was doing/learning about/thinking about,” she says.

There was a moment of panic where it seemed like she’d lost them all, but it’s OK, she figured out how to use Firefox’s cache to retrieve them all.

One of my favourite publishers in terms of their typical subject matter, Verso Books, is temporarily offering up the very topical “Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics” as a free eBook.

The Olympics have a checkered, sometimes scandalous, political history. Jules Boykoff, a former US Olympic team member, takes readers from the event’s nineteenth-century origins, through the Games’ flirtation with Fascism, and into the contemporary era of corporate control. Along the way he recounts vibrant alt-Olympic movements, such as the Workers’ Games and Women’s Games of the 1920s and 1930s as well as athlete-activists and political movements that stood up to challenge the Olympic machine.

TIL: Boris Johnson once disfigured a Long Covid report he was supposed to read by scrawling the word ‘bollocks’ over it.

Absolute moron.

Long Covid is of course, uncontroversially, very real, can be very devastating to people’s lives, and is common enough that most of us know one or more people who suffered from it to varying extents.

Back in March 2023, it was estimated that almost 2 million UK residents - i.e. the people that Johnson was supposed to be serving - actively had the condition at that time.

I wasn’t wrong about the torment nexus AI plastic necklace company called ‘Friend’ probably having had to have spent a lot on their domain name, friend.com.

404 Media reveals that the sale went through at $1.8 million dollars.

Probably makes anyone who’s been on the odd ‘novelty domain name that they’ll never use’ splurge now and then feel better about themselves though.

Revisiting the Friend site made me realise how creepy the headline image is. I don’t want a robot-brain-for-money realising I’m vulnerable. Saying the quiet part out loud and all that.

TIL: The US' current cybersecurity legislation, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, is an evolution of anti hacking laws that President Reagan introduced because he happened to watch that fantastic movie, WarGames.

From New America:

Reagan brought it up a few days later at a White House meeting that included the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and asked, “Could something like this really happen? Could someone break into our most sensitive computers?”

The answer came back a week later: “Mr. President, the problem is much worse than you think.”

I’m sure watching that film too many times as a kid proved quite foundational to my present day existence.

Naomi Alderman's 'The Future' further fed my big tech scepticism

📚 Finished reading The Future by Naomi Alderman.

This is by the same author as the rightfully extremely famous book “The Power”, which is now also a TV series. Most reviews I’ve seen seem to regard “The Future” as a distinct step down from its best-selling award-winning predecessor - not that it is a sequel as such; it stands alone. But I liked it at least as much, and possibly more, than her earlier one. Admittedly a lot of that might be because it plays directly into some of my stronger current prejudices.

It takes place in a world that’s basically a slightly ahead-in-time version of our own. There are three big tech firms that have managed to infuse themselves in almost every sphere of public and private life; let’s call them Facebook, Amazon and Apple. Well, to be fair, the book is slightly more subtle; Fantail, Anvil and Medlar. It so happens that Fantail basically does everything that Facebook does in our world, Anvil does everything Amazon does, and Medlar does everything Apple does.

Fun fact, a medlar is, in fact, a small unpleasant looking fruit which has, in its time, had such nicknames as “open-arse”. When cooked in a certain way it tastes like apple sauce. Clearly someone did their research.

Each is run by some kind of weird selfish billionaire who wields absolute power over their domain and that of their users who has an insatiable thirst for more profit. Nothing is ever enough. Just in case things go pear shaped (which, being largely in control of, they know it will happen at some point), they all have top secret bunkers to go hide out in in the event of some otherwise world-shattering event. I wonder where Alderman gets her ideas from, huh?

The story starts at a point where their fancy-schmancy exclusive AI watch - think ChatGPT but you can trust it and it costs a lot more than $20 a month - tells them that actually today is the day. It’s time to go pick up their wives and kids (if they can be bothered to) and hightail out of there like there’s no tomorrow. Because there may well not be for most of the rest of the population.

The story is vey good, but I particularly revelled in some of the descriptions of the harms these Definitely Fictional characters caused in their profit-seeking ventures.

A couple of examples:

If your data belongs to you, then you ought to decide exactly who uses it and how. You should be able to transfer it from place to place as you want, and access it as you like through any service. The reason they don’t let you do these things is not because it’s hard; it’s because it doesn’t make them more money.

This is not only true in the real world but it illustrates how contingent some of these decisions are, how deliberate and unnecessary. What seems inevitable in the world of technology rarely, perhaps never, is inevitable. It’s choices made by extraordinarily privileged people.

Another such choice that plagues our real world:

The type of emotional optimisation Anvil and Medlar and Fantail did as a matter of course every day. Each of their websites, thinscreen interfaces, smart torcs, burst displays and mobile phone applications had specific commands about what to show and what to bury. Certain emotions drove high engagement - people looked for longer at things that made them angry or afraid…

…

These sites presented themselves as a clear pane of glass through which you could see the world as it was. But they were really a distorting visor, showing you the version of the world that worked best for the board and stockholders of the companies

Algorithms are not inherently bad and wrong. It’s the choice of what to optimise them for that makes them so.

It wasn’t preordained by mystical forces that the primary goal of all mainstream social media networks, amongst other publishing entities, needed to be to capture the attention of users for longer than the users actually wanted to give it to them and make them click on things they didn’t really want to click on. It was preordained by the economic structure “we” chose to live under and the choice - choice! - of business structure that these organisations all ended up going with.

In another world - not Alderman’s one either - the goal could I have been, I don’t know, create world peace perhaps. Or at least try and make your users go away happy rather than angry and upset.

Unfortunately I can’t stop myself now. Here’s another snippet:

We despise the animals because they don’t think just like us, we use them and we hurt them. We invent gods, we invent aliens, now we make a friend out of fucking matchboxes. We want to say it “thinks” but is not true. We want to give it everything, let it make choices, believe it can care for us. It is image of a man made of paper and beads and we so fucking lonely we call it a friend.

Umm, have you visited friend.com recently?

I’ll stop before I give too much away, but if you hold any kind of scepticism about big tech, social media, AI, that kind of stuff then there’s probably something you’ll like here in a philosophical sense. If that’s something you’ve never thought about all that much, which I assume is the case for most normal sane folk, then you might inadvertently learn something about some of the problems people see with these systems by enjoying this novel. And if you don’t care about the topic at all, or virulently disagree with the passages I have to be fair very much handpicked to make a point above, then, well, hopefully you’ll still enjoy the story.

Once again, managing a government budget is not like managing a household budget

I always appreciate seeing a reminder as to why, despite what politicians from several parties insist on telling us, managing government spending is nothing at all like managing a household budget. And thus, the logic you use when doing so should be entirely different.

What you need to do to act as a ‘responsible’ householder under the present framework is different to what you need to do to act as a responsible government minister. Pretending that they’re the same thing is irresponsible (and in fact often represents a misunderstanding of how sensible people do manage household budgets).

Aditya Chakrabortty provides a nice quick summary of many of the relevant factors in an article from today’s Guardian called ‘The cynical spectre of Osbornomics is haunting the Labour party':

…unlike individuals, nation states don’t retire or die; that no household hides a government’s printing press or tax department in its loft conversion; that most families do borrow to invest (for what else is a mortgage?) and will spend cash to keep kids from going hungry

These aren’t the only reasons. A couple more that come to mind include:

- The choices a household makes tend to impact only themselves to any large extent. The choices a government makes can impact the whole nation, its whole economy.

- If a household doesn’t buy a luxury holiday this year then it doesn’t necessarily affect other aspects of their budget. It just saves the holiday money. Whereas cuts to public service costs in one area for example often lead to rises in expenses for other area. A classic example of this would be a reduction in GP services tends to lead to an increased demand for (more expensive) hospital services. Sacking 1000 civil servants? That’s 1000 more people who may require benefit payments, training, education et al for a while.

This doesn’t mean a government in a country with its own currency operates with no constraints of course. Liz Truss’ rapid destruction of our economy proved that.

They’re just different, usually lesser, constraints. And at the end of the day, if it needs money to solve any given emergency, it has that money if it chooses to have that money.