New Employment Rights Act ‘a huge boost for women in the workplace’: A rare bright spot in the smorgasbord of disappointment from the UK’s Labour government.

Recently I read:

UK must stockpile food in readiness for climate shocks or war, expert warns: ‘The first UK Food Security Report in December 2021 found the country was 54% food self-sufficient’

Latest posts:

Ooh, after the success of the Super Mario Bros Movie they’re making a live-action Legend of Zelda film.

TIL: The collective noun for a group of ferrets is a “business” of ferrets.

So now you know the easiest way to become a business owner.

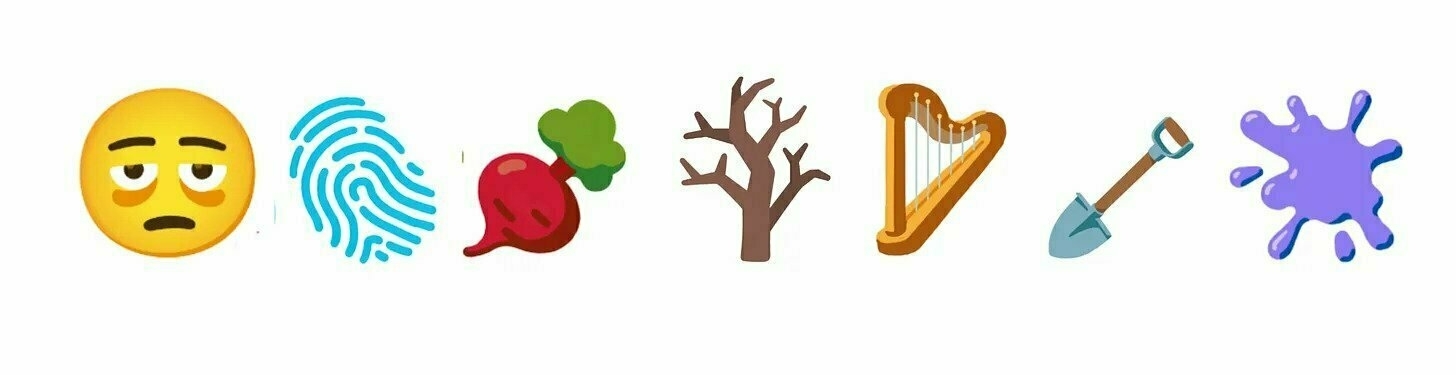

Jennifer Daniel shares what we can expect for official new emojis in 2025.

Just seven this time, apparently selected for their linguistic flexibility, amongst other things.

- Face with bags under eyes

- Fingerprint

- Root vegetable

- Leafless tree

- Harp

- Shovel

- Splatter

Leafless tree could apparently be used to represent a “state of barrenness and death” which feels very 2023 at least. Face with bags under eyes is surely another that contemporary times will inspire great use of. Unless of course by 2025 we either managed to fix the world or destroy it enough that all that remains of us is splatter .

The UK does not need to widen the definition of extremism even further

Via some leaked documents the Observer got their hands on, we learn that the government is thinking about widening the formal definition of ‘extremism’ such that it’ll read:

Extremism is the promotion or advancement of any ideology which aims to overturn or undermine the UK’s system of parliamentary democracy, its institutions and values.

You don’t even have to be doing ‘extremist things’ yourself. You might just not be disapproving of the folk that do hard enough.

Part of the definition that this Brave New World of people who spend their time sitting in other people’s cars talking about freedom and their friends will be considering, if the leak doesn’t kill it, also includes:

Sustained support for, or continued uncritical association with organisations or individuals who are exhibiting extremist behaviours

I’ve a slight worry that this blog, perhaps even this post, will become technically ripe for a referral to the anti-extremism authorities.

I mean, with the criteria of undermining ‘the UK’s system of parliamentary democracy’ featuring up top, might we be in theoretical trouble for having cast a vote in favour of changing the electoral system we vote under in the 2011 national referendum? What remains of the Lib Dems better watch out!

The various civil rights groups we have are rightly rather unhappy about this.

From the director of Liberty:

This proposed change would be a reckless and cynical move, threatening to significantly suppress freedom of expression

The editor of Index on Censorship:

This is an unwarranted attack on freedom of expression and would potentially criminalise every student radical and revolutionary dissident.

The racial justice director of Amnesty International:

The definition of extremism and its usage in counter-terrorism policies like [counter-terrorism strategy] Prevent is already being applied so broadly it seeks to effectively hinder people from organising and mobilising. The proposed definition takes this even further and could criminalise any dissent.

The leaked Govenrment document lists some organisations that they’d consider as being ‘captured’ by this proposed new definition. These include Muslim Council of Britain, Palestine Action and Muslim Engagement and Development.

It’s not like the current definition of extremism we have is particularly narrow.

…active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs

But I suppose at least you have to be ‘actively opposed’ at present. And, judging by the fact that more of our politicians aren’t in extremism jail, it seems like at least the latter part of the definition isn’t particularly strongly enforced.

Not that it’s stopped at least 45 peaceful environmental activists being referred to the Government’s current anti-extremism program. That situation that provoked Liberty to speak out once again at the time:

This reinforces long-held concerns that the government’s staggeringly broad definition of extremism enables the police to characterise non-violent political activity as a threat, and monitor and control any community they wish.

As ever, even if for some absolutely inexplicable reason you trust the current government and other arms of the state not to abuse the extraordinarily wide definitions of these very hot-button, very political, very emotional topics, one must remember that things change. Some even worse folk could come along in the future. And it’d be nice if they didn’t automatically inherit the power to silence or punish anything that could be vaguely categorised as dissent against their preferences.

I often wondered what happened if you accidentally tick the “Yes I have committed genocide” box on the strange form you’re asked to fill in when travelling to the US.

For the uninitiated, as part of the visa-waiver process to fly from the UK to the US you have to fill in your details and answer a series of increasingly harrowing questions, the apex of which is being asked to respond yes or no to:

Do you seek to engage in or have you ever engaged in terrorist activities, espionage, sabotage, or genocide?

Of course it turns out that inadvertently ticking the yes box has happened more than once so there’s an answer. It seems to be more along the lines of subjecting you to hefty delays, cancellation and expensive bureaucratic hoops to jump through rather than getting thrown in jail. I’m sure it’s still annoying though.

Stories abound.

First there’s Mandie who encountered an obstacle in working through her bucket-list.

Cancer patient Mandie Stevenson had to postpone a bucket list trip to New York after she accidentally labelled herself a terrorist on her visa waiver form.

Then a prospective Christmas vacation was ruined for an older gentleman:

A Scottish couple’s festive holiday plans are in disarray after a 70-year-old grandfather accidentally declared himself a terrorist on a crucial visa form.

He’s now afraid he’ll never be let in.

“They looked up my Esta number and said ‘you’re a terrorist’. I told them that I was 70 years old and I don’t even recognise what that means.”

Finally for now we have someone at the other end of the age spectrum.

A three-month old baby was summoned to the US embassy in London for an interview after his grandfather mistakenly identified him as a terrorist.

But was it truly a mistake? Perhaps only mostly.

“He’s obviously never engaged in genocide, or espionage, but he has sabotaged quite a few nappies in his time, though I didn’t tell them that at the US embassy.”

volunteered his grandfather.

Verso Books is the largest independent, radical publishing house in the English-speaking world, publishing one hundred books a year.

I just discovered that Verso appears to have a book club that threatens to be extremely dangerous in terms of adding vast backlogs to the TBR list of anyone that way inclined.

From just £8 a month they send you copies of every new book they publish that month - or you can pay a bit more to get a couple of of physical books on top of that. So that’s going to add 100 probably fairly heavy-going books per year to the now-entirely-detached-from-reality schedule.

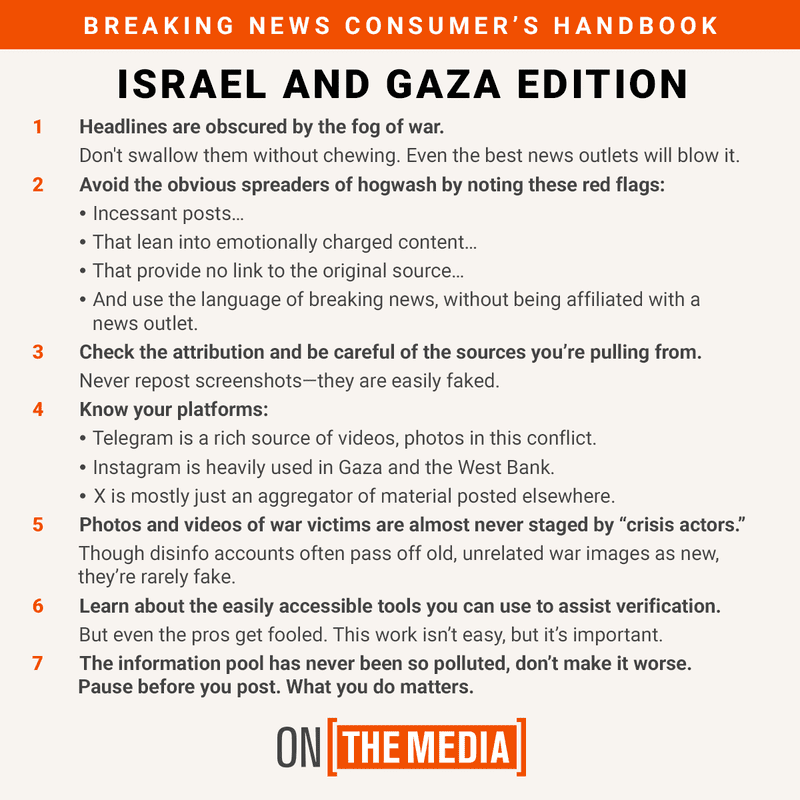

🎙️ Listening to ‘Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook: Israel/Gaza Edition’ from the On The Media podcast.

The maelstrom of mis and disinformation circling the conflict in Israel and in Gaza is some of the worst that researchers have ever seen.

On The Media has produced another one of their breaking news consumer’s handbooks, this time targeted at how to treat supposed news on the topic of the current Hamas / Israel conflict that you see emanating from wherever you might encounter news.

Their summary is shown below. The podcast talks through the points in more detail. Definitely stuff worth considering to keep from becoming an info-victim of engagement farmers or worse.

The impact of the Hamas Israel war on hate-crime in Britain

What’s going on in the Middle East at the moment - after Hamas committed an appalling attack on Israel and Israel responded with an all-encompassing war - feels too mind-bendingly awful to sensibly comment on.

But it is an extra shame to see how it, as world events often seem to do, translates to an senseless, pointless, futile increase in acts of criminal hatred and violence in faraway places.

So far this month there’s been 174 incidents of Islamophobic crime recorded in London, which is an increase of 176% compared to the 65 reported in the same period last year.

The increase in anti-Semitic offences has been even higher. There’s been 408 such offences recorded. That’s an increase of almost 1400% compared to the 28 recorded in the same period last year.

The police have made 75 arrests so far that they say are linked to the conflict.

In general, crime report statistics are notoriously difficult to interpret. There are many reasons that crime report numbers can change that are unrelated to the number of crimes that actually took place. But these changes are so stark and so sadly explainable and predictable that it’s hard to imagine this shift isn’t real.

🎶 Listening to The More Red Chapter by Taylor Swift.

Whilst these differently compiled re-releases seem all a bit targeted at making either more money, more algorithmic domination, or both for the recently-crowned dollar billionaire artist, this one does seem specifically targeted at my Swiftian preferences.

I guess I’m not the only one given the enthusiasm created at one of her recent concerts generated literal seismic activity equivalent to a magnitude 2.3 earthquake.

The Guardian also did a recent podcast on the rise of the global Swift empire.

🎶 Listening to The Jaws of Life by Pierce The Veil.

This is their first album in a 7 years. Emo pop punk kind of stuff which makes me wish that Guitar Hero was still a thing. Or that I’d kept up guitar lessons back in the day I guess, but the former seems more realistic.

🎶 Listening to Just a Christmas Dirtbag by Wheatus.

There’s something a bit tragic about bands you thought were cool as a kid fully selling out to Big Christmas, but also you do get to hear what Teenage Dirtbag would have sounded like had Santa Claus been the object of desire.

It’ll make a refreshing change from Mariah Carey.

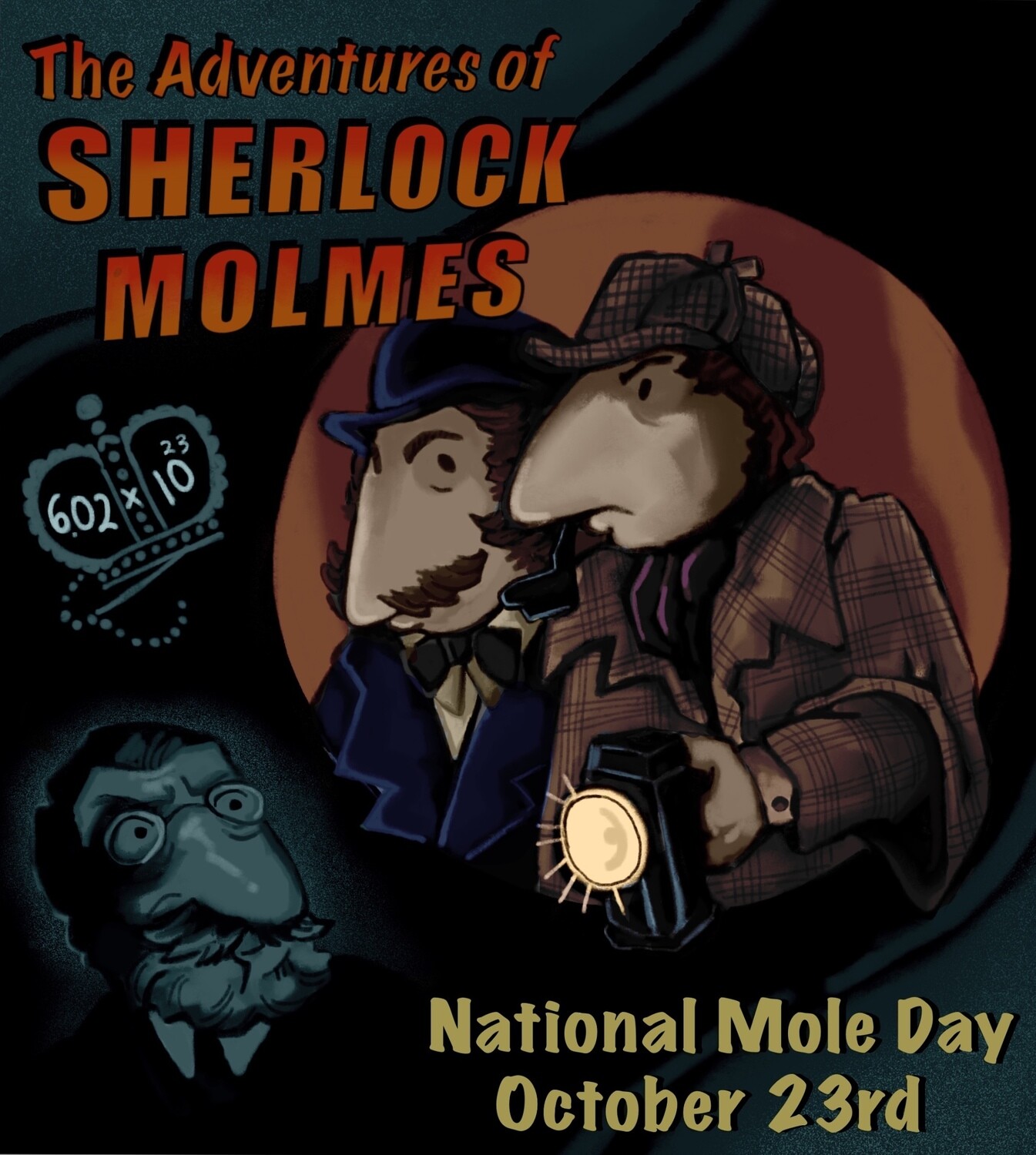

I’m sure no-one needs reminding, but today is National Mole Day. . Nothing to do with small furry garden-diggers, although this year’s mascot might indeed be one the famous Sherlock Molmes.

Rather it’s a celebration of all things Avagadro’s Constant from 6.02am through 6.02pm every October 23rd.

Avagadro’s constant is 6.02 x 10^23 and thus on the date Americans call 10/23 at 6:02 it needs commemorating.

For anyone who forgot chemistry, per Wikipedia it’s useful as a kind of conversion factor:

The Avogadro constant is also the factor that converts the average mass of one particle, in grams, to the molar mass of the substance, in grams per mole (g/mol)

That’s to say, given that a water molecule has a molar mass of 18 - the oxygen provides an atomic weight of 16, and each of the two hydrogen molecules contribute 1 extra - we define one mole of water as the amount of water that has a mass of 18 grams. And to end up with 18 grams of water you need lots of water molecules, more specifically 6.02 x 10^23 of them.

In the same way if you wanted 16 grams of oxygen, you’d need to find 6.02 x 10^23 molecules of it, and so on.

Unsurprisingly, the 'eat 2000 calories a day' recommendation isn't very scientific

TIL: The 2000 calories per day recommendation you see on food labels that say things like “Eating this biscuit uses up 20% of your recommended daily calorie intake” is not really based on a ton of rigorous science.

Rather, it seems to be a very rounded version of a wide-ranging number of calories that Americans reported eating on a survey from a few decades ago. So it more represents vaguely what the average person reported that ate 33 years ago than something that is in theory an actually recommendation for what you should eat.

From US News:

….not only was the calorie standard not derived based on prevalent scientific equations that estimate energy needs based on age, height, weight and physical activity levels, but the levels were not even validated to ensure that the self-reported ranges were actually accurate.

In general I believe there’s multiple studies out there that suggests that self-reported food consumption tends to systematically underestimate what was actually consumed - for example “Traditional Self-Reported Dietary Instruments Are Prone to Inaccuracies and New Approaches Are Needed”

Plus people’s needs vary a lot based on at least demographic and behavioural factors. There are plenty of people for which 2000 is substantially more than would be recommended if their goal was to maintain their current weight.

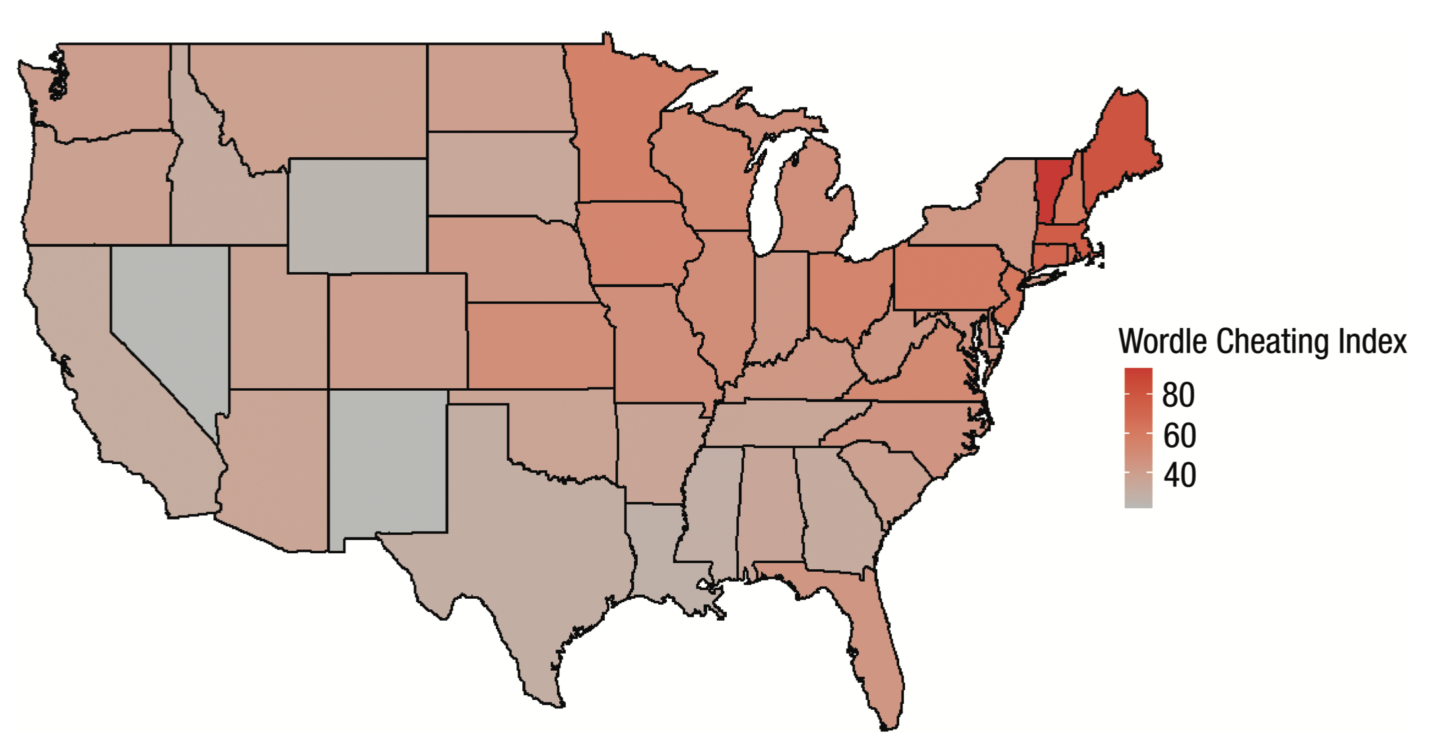

In a recent paper, researchers compared the trends in Google searches that suggest people are looking up the answer to the formerly-ubiquitous word game Wordle with tweets from US players of the game.

An important note for the handful of people that don’t know how Wordle works is that if you lose the game then it tells you the answer, so I suppose the premise is that if you’re independently looking it up you must be up to no good.

The claim is that people who live in states that are more religious or ‘culturally tight’ - having stricter, stronger, more enforced social norms - are less likely to cheat at Wordle.

Behavioralscienist.org reproduces one of their charts.

Intuitively I feel like there’s plenty of other possible explanations for this pattern out there - the paper is paywalled so I haven’t read the full thing to know what else they considered and to what level of rigour.

But in the mean time, never trust an East Coast wordler I guess.

Can’t believe its taken me 7 years to learn of the outrageous decline of everyone’s favourite combination chocolate treat / weapon: the Terry’s Chocolate orange.

It’s been air-gapped!

From Wikipedia:

On 29 May 2016, the UK product size was reduced from 175g to 157g by changing the moulded shape of each segment to leave an air gap between each piece.

I guess they thought noone would notice that the last two digits of the weight had been swapped around.

Compounding the crime:

Despite this, the price doubled in some retail outlets.

The real AI alignment problem

🎙️ Listening to The Ezra Klein Show podcast episode “Why A.I. Might Not Take Your Job or Supercharge the Economy”.

I think he’s spot on regarding the real AI alignment problem.

Sure, it’s possible that some super-powerful computer brain will eventually decide to remove the human race so it can get on with manufacturing paperclips. If anything remotely like that is a plausible scenario then of course we need to work on the knotty problem of “traditional” AI alignment before it’s too late.

But not at the expense of our present-day major AI-related alignment problem. Today’s critical AI alignment problem is that the basic motivations of the organisations that develop, own and often hold some kind of monopoly over the most powerful AIs are usually not aligned with the public good in general, and almost never aligned with protecting or promoting the interests of the worst-off in society.

Right now, AI development is being driven principally by the question of can Microsoft beat Google to market? What does Meta think about all that?

The interests of companies, governments and some other types of institutions are not usually aligned with the interests of humanity as a whole. I’d probably generalise even further to say that the greater social and economic structures that most of us live under now are not aligned with the interests of the majority of the people enmeshed in them today, whether or not they may have served us well in some ways in the past.

Admittedly the veracity of these sorts of claims of course always depends on what you feel society should be optimised for, it’s subjective rather than objective. But it doesn’t seem likely to me that in a world where a primary motivation for the most cutting-edge AI development is something like “How can Big Tech company X make a more impressive seeming and addictive chatbot than company Y such that its shareholders get richer faster?” is likely to produce the best possible result in terms of maximising the benefits for almost any of humanity.

Google’s main revenue stream remains advertising. Assuming that persists, I doubt society as a whole is going to benefit much by Google’s brightest minds figuring out how to use these amazing new technologies to build better adverts, to make us click on more things we’re not really interested in, more likely to buy things we don’t really want.

Sure, the natural focus of these companies might help those who - to borrow a famous phrase - own the means of production become ever more rich, ever more monopolistic, ever more exploitative. But beyond that why should we imagine that a product designed to make shareholders rich would be especially aligned with any other outcome?

I do not want the shape and pace of AI development to be decided by the competitive pressures between functionally three firms. I think the idea that we’re going to leave this to Google, Meta and Microsoft is a kind of lunacy, like a societal lunacy.

Generating extra money for rich people may not be the primary personal driver for developers in these fields. In fact I’m sure it’s not. No matter our job, few of us turn up each day exclusively motivated by the idea that by end of our workday we may have increased the wealth of some other firm’s investment managers.

For a start, a certain type of person, me included, finds these technologies to be intrinsically interesting - witness the rapid development of open source alternatives to the big tech AI tools that have been rapidly developed by volunteers. Albeit volunteers that usually don’t have access to anything like the massive resources that the Big Tech firms can bear to these tasks.

And if modern-day AI tools are as revolutionary as some believe then there’s a huge amount of increased social good potentially within our grasp, especially if we believe that most people are fundamentally “good” in important ways. But people operate inside contexts that provide structures often far more powerful than the individual in terms of promoting their own rules, regulations, incentives and goals.

I think you have to actually ask as a society, what are you trying to achieve? What do you want from this technology?

If the only question here is what does Microsoft want from the technology? Or Google. That’s stupid. That is us abdicating what we actually need to do.

Of course this general idea doesn’t only affect AI. It’s a constant battle in the world of technology and beyond.

IPleak.net looks to be a pretty comprehensive website that allows you to check what IP address websites you visit see you as coming from as well as various other bits of info your computer might be leaking to advertisers and other dodgy operators. Your IP address can be used to establish various bits of info about you such as who your ISP is or whereabouts in the world you are for example.

The site also shows you what can be established from the DNS servers you’re using, what information is available to others from your web browser and even has a clever way to see what IP address any torrents you might prospectively be considering downloaded will see to via adding a “fake” magnet link to your Torrent client.

Newspaper in trouble for publishing Braverman's lie about child grooming gangs

IPSO rules that the Mail on Sunday must apologise for publishing an article by Suella Braverman that claimed that almost all child grooming gangs in the UK are of British-Pakistani origin due to ‘cultural attitudes completely incompatible with British values’.

Our esteemed Home Secretary’s claim is of course a lie.

The regulator said Braverman’s decision to link “the identified ethnic group and a particular form of offending was significantly misleading” because the Home Office’s own research had concluded offenders were mainly from white backgrounds.

I feel a tiny, tiny bit of sympathy for the paper in that apparently they did double-check the claim with the offices of the Home Secretary and the Prime Minister. And it’d be sort of fair in a less ludicrous world to assume that any normal boss of a department wouldn’t publicly and provably lie about about the research that their own department did. But by now we surely all know that we clearly don’t live in that kind of world.

📚 Finished reading Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia.

Rich young partygirl Noemi - more used to the 1950s Mexico City socialite scene than anything more gothic in nature - is persuaded to go see what’s up with her recently-married cousin Catalina after receiving a strange letter from her claiming that she’s being poisoned and that her very house is filled with “these restless dead, these ghosts, fleshless things”.

No-one is takes these weird haunted house claims literally, although sure enough when she turns up the house is a big old isolated mansion, very creepy, rotting away, covered by mold and fungus. She meets a few inhabitants who are a bit weird, in similarly creepy, slightly stereotypical, ways.

But what about her previously well-adjusted cousin? Is she really being poisoned? Does she suffer from some malady, whether of the physical or mental realm? Or is her “I see dead people” (in walls) claim somehow the truth? Well, I’m obviously not going to spoil that. Other than to say that what goes down is a bit grotesque in places, but suitably so.

If one wants to read a little more deeply and generally into the tale, there are obvious callouts to themes of female disempowerment, the colonisation mindset, the absolute exploitation of people deemed lesser than the (once) rich and powerful who have somehow managed to delude themselves into believing in their own innate superiority.

The house is a character unto itself, dark and isolating. Insanity - if that’s what it is? - confusion and disorientation prevail, with an increasing sense of dread. Many of the mainstays of gothic literature are to be found. But even without the political analysis, I found it a compelling and creepy read.

Walmart finds that people who start taking the GLP-1 anti-obesity medications go on to buy noticeably less food compared to trends with other customers - ‘less units, slightly less calories’.

📺 Watched Jury Duty.

Caved into the show that almost every American I know seems to be talking about. It’s a reality gambit where they follow a guy who believes he’s taking part in a documentary about how the US judicial system works from the point of view of being in the jury.

Only of course everyone else he encounters - the fellow jurists, the bailiffs, the judge, the complainant, defendant and their litigators - really everyone - are actors and the case is entirely fictional.

Of course semi-scripted hijinks ensue and we get to wonder if and at what point we might ever have realised what’s going on had we been selected.

On the surface it seems like in Ronald Gladden they’ve found the most amiable, well meaning, diligent and balanced person out there for their mark. Someone who might actually be able to handle every facet of his dutiful existence for a few weeks turning out to be entirely fake, a real life Truman Show.

Fervently hoping he won’t end up being a milkshake duck. And that the camera crews come back if he ever gets selected for jury duty for real. What would it take to convince him this time it’s for real?

Oh - beware this paragraph might be a bit spoilery - but I felt compelled to check and it turns out that the practice of soaking isn’t something the show invented. it’s (probably) real courtesy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints amongst other venerable institutions . And they did have a plan for if Ronald was a bit more enthusiastic about it.

🎶 Listening to Re: This Is Why.

Ever wondered what it’d be like if the recent Paramore album had actually been recorded by a variety of different bands? Well, this is that.

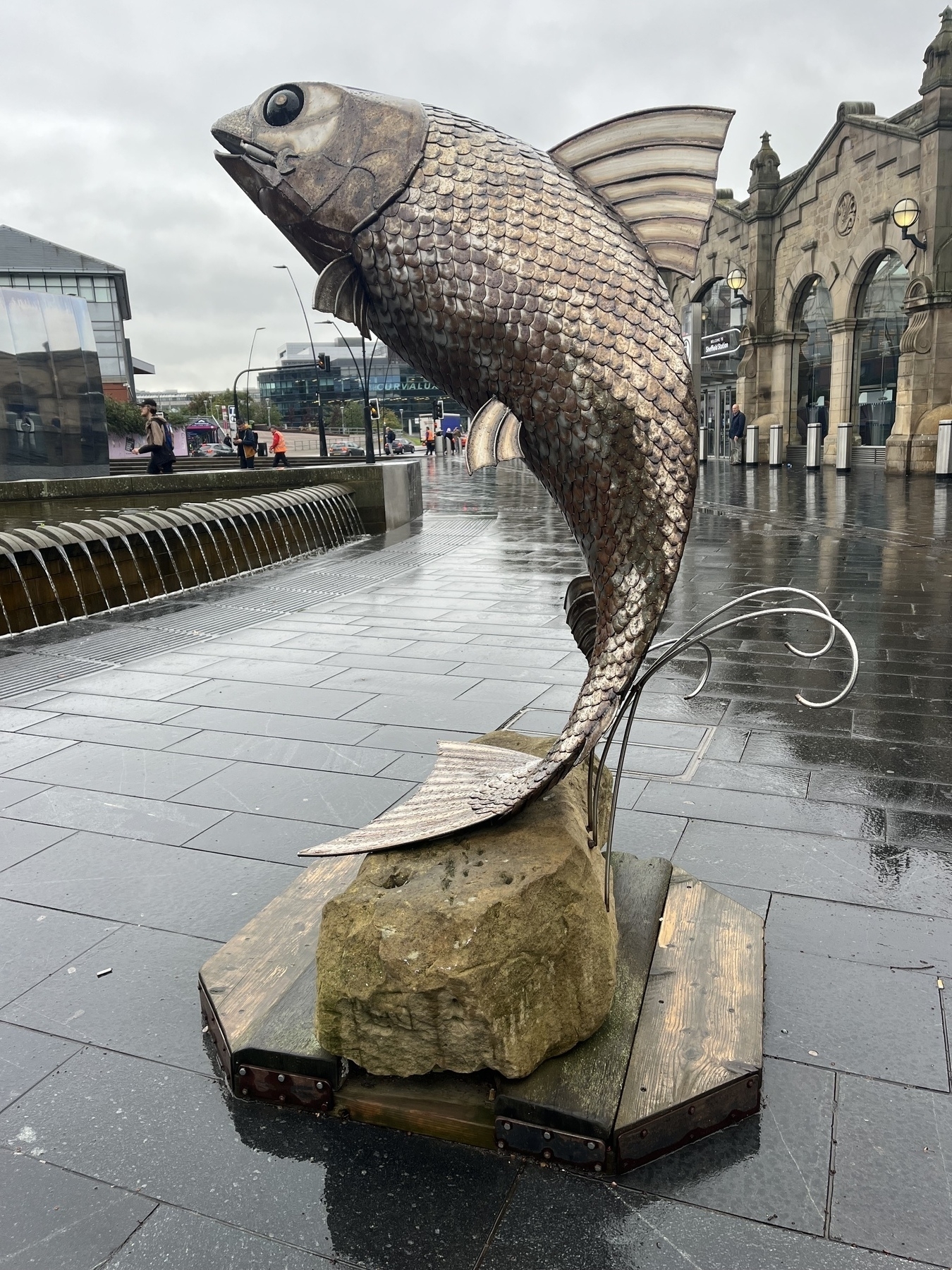

A wet fish, outside Sheffield station.

I was curious to know what age the oldest person to have ever lived got to. According to the Guinness World Record folk it’s Jeanne Louise Calment, from France, who sadly died in 1997, aged 122.

That means she was born in 1875. At the age of 14 she watched the Eiffel Tower being built. At age 85 she took up fencing as a sport. At 114 became the oldest film actress ever. 6 years later she became a recording artist.

New contenders have emerged since then, but it doesn’t look like the Guinness World Records folk have managed to authenticate them as yet.

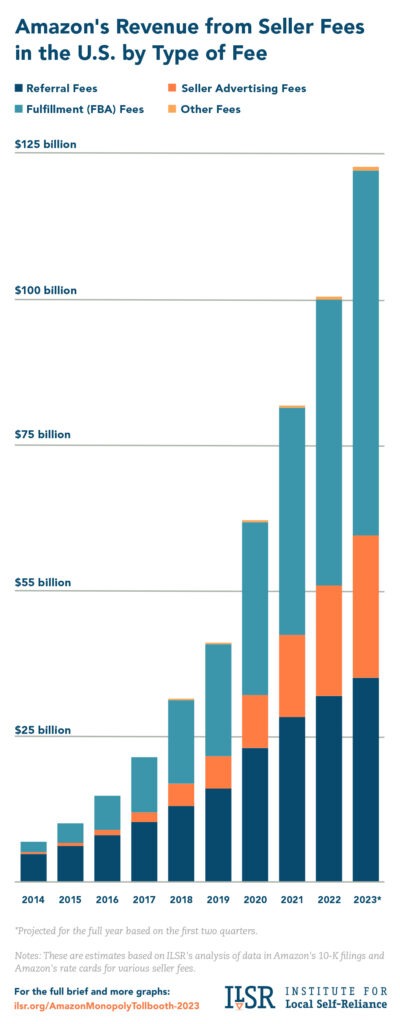

Amazon now charges third-party sellers almost half of their revenue

Monopolies gonna monopoly. Now that Amazon is so dominant that many online retailers feel like they have no choice but to sell their products via them, Amazon squeezes them ever harder. At this point their fees represent almost half of the third-party sellers' revenue.

In the first half of 2023, using a variety of fees, Amazon took 45 percent of sellers’ revenue in the U.S. That’s up from 35 percent in 2020, and 19 percent in 2014.

Unsurprisingly, most of those businesses go on to fail.

The three main categories of costs are the:

-

Referral fee: usually 15% of the revenue. This was previously the only or main cost charged to sellers for listing their products on Amazon.

-

Advertising fees: which counter to many people’s intuition includes not only the more obvious adverts, but also the products Amazon highlights as “highly rated” and other such categories. You might think that the “highly rated” products are the products rated most highly on Amazon. But no - they’re the products someone is willing to pay to be featured. The consequences of this also affect their placement in the general Amazon search results. Apparently most sellers feel like they have to use these features to stand a chance of getting sales.

-

The fulfillment fees. These are charged for the privilege of having Amazon warehouse and ship your product. Most of the top sellers pay for this. Why? Because if not the products are not permitted to be eligible for Prime, which puts customers of - a new policy brought in 3 years ago. Because running 2 fulfilment services is expensive this tends to mean suppliers send their non-Amazon originating orders through “Fulfilled by Amazon” too, again increasing their take.

Amazon collects enough money from these fees - $82 billion in the first half of 2023 - such that it covers the entire cost of fulfilling both the third party orders and their own direct Amazon sales. Thus Amazon doesn’t need to consider warehousing and shipping costs for their own products, because the money they charge third party sellers to cover their fulfilment costs in fact also pays for Amazon’s own fulfilment costs. This is one reason why they can advantage themselves ever further by offering consumers lower prices than there is any hope that their rivals could match.

I don’t know how this next rule is legal, but sellers are also required to never charge less for their products on other sites than they do on Amazon if they want to sell anything on Amazon.

This means that sellers can’t pass the costs Amazon imposes on them to their own buyers who choose to use the Amazon ecosystem. Either they have to take the hit themselves, or they have to build the cost of operating with Amazon into the prices of every product they sell anywhere. This then either results in the business having to raises their prices to consumers irrespective of whether Amazon was involved or not, or making it that extra bit less likely for the business to survive for long enough to become sustainable.