Recently I read:

The left is missing out on AI: ‘…ceding debate about a threat and opportunity to the right.’

In 1984, An Unemployed Ice Cream Truck Driver Memorized A Game Show’s Secret Winning Formula. He Then Went On The Show: …and became rich, for a while.

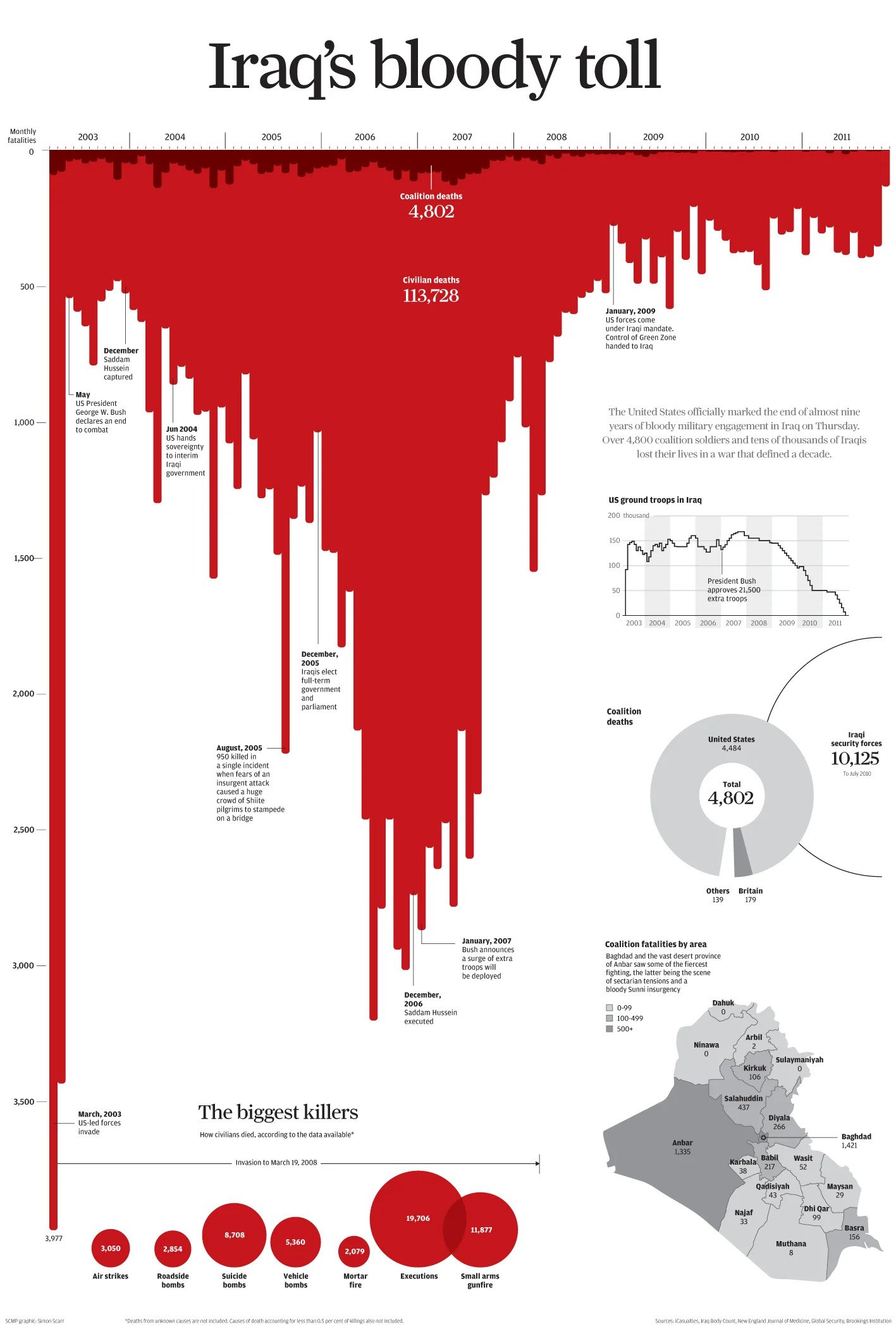

The 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq

It’s just been the 20-year anniversary of one of the more formative-to-me and likely damaging-to-the-world political episodes I can remember from my youth: the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This was spearheaded by US president George Bush, with the UK’s Prime Minister, Tony Blair, often portrayed as Bush’s poodle (a take that I now know is unfair to actual poodles), joining in amongst others.

As the BBC summarises, it did not go well.

There’s no question that Saddam Hussein was appalling. Truly horrific. Famously, decades ago he’d even used chemical weapons to commit atrocities against his own citizens. There’s no serious doubt that his removal should in theory have been a very good thing. But as to who should remove him, how, for what reason and, all-importantly, what should happen afterwards are all issues where, let’s say, suboptimal decisions were taken.

The motivation given to us, citizens of “the coalition of the willing”, was something mainly along the lines of “Saddam Hussein is behind al-Qaeda’s acts of terrorism” and “he has illegal weapons of mass destruction that can be deployed in the next 45 minutes”. Those sentiments were widely contested at the time and sure enough turned out to be untrue.

The UN process was overlooked, to the extent that most likely the US-led invasion was illegal. It certainly caused tension with some NATO allies who declined to join in. There were huge protests against the invasion in the UK, but our government decided to go ahead anyway. Global institutions such as the UN were weakened, potentially leading to some of the poor responses the rest of the world has made to other such geopolitical crises since then.

Saddam was removed from power relatively quickly, but what transpired next was something like an insurgency against a US-ordained occupation. As time went on, a lack of effective government exacerbated the eruption of essentially a civil war between the main ethnic or religious groups in Iraq, with Jihadists groups joining in. The extraordinarily violent extremist group ISIS - the “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” - thrived.

All in all, the abject failure of the approach that the US and its allies took left the world a worse and more dangerous place. The post-invasion conditions in Iraq itself got so bad that some Iraqi’s reportedly consider the days when they were under Saddam’s tyranny as better than what came next.

From the BBC article:

It is a sign of how bad the past 20 years have been that Saddam nostalgia is well established in Iraq, not just among his own Sunni community. People complain that at least you knew where you were with the old dictator. He was an equal opportunities killer of anyone he saw as an enemy, including his own son-in-law.

Of course all the people Saddam killed are unable to express an opinion. But neither are the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who died as a result of the invasion, and potentially some of the uncountable number of people who would go on to be negatively affected as part of the downstream consequences.

Trying to quantify a small part of that also resulted in one of the most haunting and memorable graphs I can recall ever seeing; Simon Scarr’s “Iraq’s Bloody Toll”.

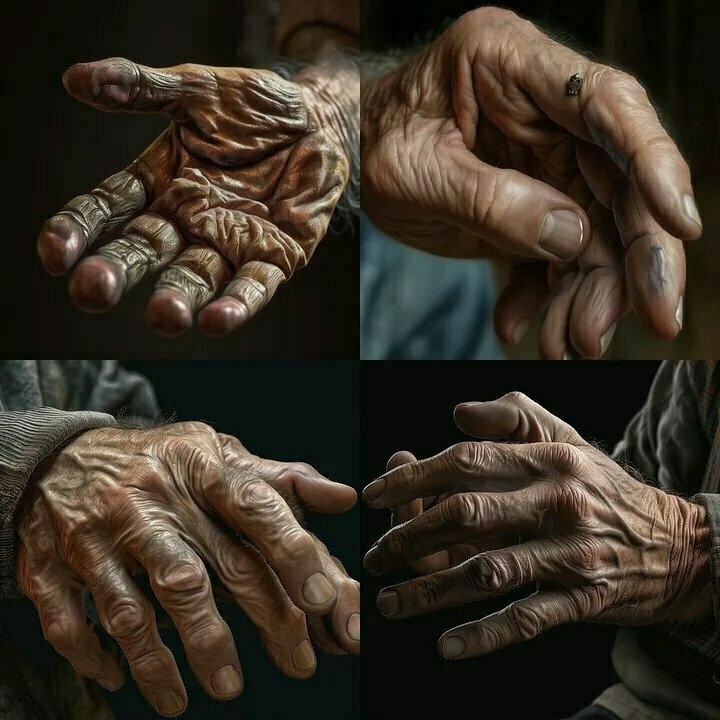

AI image generator Midjourney recently released its version 5 and apparently not-too-disturbing “photorealistic” human hands are now within reach.

From Del Walker’s tweet:

That said Michael King’s Medium post shows it could hardly be described as perfect just yet:

The release of GPT-4 has led to a flurry of mind-bendingly impressive tricks that I mean to create a list of. Unfortunately it also enables grim but inevitable services such as CupidBot.

This abuse of cutting-edge AI software allows men - yes, only men, heterosexual men at that - to have a bot log onto their various dating app accounts, do their swiping, chatting and setting up of dates with no intervention required (outside of a monthly subscription fee).

The idea is that it automates everything from partner selection up to where you will go for a date, so you just need to turn up. Of course this is done without disclosure to prospective partners, so it’s pure deception. It’s surely against the terms of these services, but they “guarantee you that your account will not be banned for using the bot as the AI mimics human behavior to a tee”.

I mean, “we have the data on how to talk to girls for optimal results.”. It’s turn-of-the-millennium style Pick-Up-Artistry brought into the dark timeline of 2023 automate-everything existence. It’s a shame we don’t seem to have moved onto some pleasanter idea of humanity when even Neil Strauss himself is “in the camp that any manipulation is not a good thing”.

Happily, a (female) friend observes that the fact the homepage has a calendar displaying an artificially-created “breakfast date with Lacy at her house” is clear evidence that this was designed by men for men, and so with luck may be useless in practice. Imagine inviting some Hinge randomer to your house for breakfast on your first date.

All About Love, by bell hooks

📚 Finished reading All About Love by bell hooks.

Here the author tells us to consider love as something you do, not something that is; a verb rather than a noun. She likes Erich Fromm’s definition of it as:

…the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth. Love is as love does. Love is an act of will - namely, both an intention and an action.

The media infusing our world - romantic comedies being one of the most obvious examples - makes it all to easy to confuse love with something else; perhaps attraction, care, connection or affection. The latter categories can co-exist, and may by definition have to, with love - “approaching romantic love from a foundation of care, knowledge and respect actually intensifies romance”. But they’re distinct.

This has some implications. If you love someone then you will not deliberately harm them. You will not seek to dominate them. So, conversely, if you deliberately harm someone you cannot love them.

…we cannot claim to love if we are hurtful and abusive.

By definition this precludes some parents from rightfully claiming to love their children. In fact:

One of the most important social myths we must debunk if we are to becoming a more loving culture is the one that teachers parents that abuse and neglect can coexist with love.

Furthermore, love is a choice. You do not uncontrollably fall in love. You feel uncontrollably be attracted to someone, but that’s something different. If love is something you do, then you have to choose to do it. And if you do want to do so, then it takes time and commitment.

She considers love as a more universal construct than how we typically employ the word. It may have a different meaning to us as individuals. It may be enacted and demonstrated differently. But her view is that there’s nothing qualitatively distinct about love for a romantic partner compared to that for others you are close to, or members of your community - “There is no special love reserved for romantic partners.”

She makes a lot of the distinction between love as usually practiced by males as distinct from females. The way we’re brought up, the ideas infused into us by our surroundings, the structure of the society - especially the patriarchal and capitalistic parts of it - result in us failing to recognise or practice love in the way that would cause us and the recipients to flourish as much as they could.

The patriarchal aspects of our society are undoubtedly most unfair and harmful to women who learn for instance that to be worthy of some flawed misconception of love they must be good girls, submissive, constantly tending to the emotional needs of stunted men with no expectation of reciprocation. After all, they’re compelled to live in a world where seemingly “most men use psychological terrorism as a way to subordinate women”. But it’s not like men aren’t constrained by any expectations: “how can any of us communicate with men who have been told all their lives that they should not express what they feel?”

Perhaps somewhat pessimistically, she suggests that:

most of us will go to our graves with no experience of true love.

But we can hardly be dismayed at that, because we actively flee from it.

…most of us run the other way when true love comes near.

Nonetheless we learn to be needlessly terrified of the prospect. On one hand much of the modern world is ever more cynical above love. It’s a myth, it doesn’t exist, it’s Hallmark making us buy cards. On the other hand almost everyone appears to desperately seek this thing that they don’t really believe exists.

We learn to lie and mislead other people, almost to trick them into being our partner. This is perfectly normal behaviour; there are popular relationship books in every bookshop that give advice on how best to do this, “The Rules” being one such famous one. The author sees this alone as being a reason why many people will never know love

We only feel like there’s a chance we could be ourselves after we ensnared someone and yet somehow we expect that to go well. Our desperation and fear sees us behave and tolerate behaviour from partners and immediate family members that we’d never consider from our friends or community. We may want a partner more than we want love, to the extent that we may be scared to dwell our own needs in these matters under a misguided fear that “carefully choosing partners will reveal there’s no one for us to love”.

Even if we make the right connection, we’re disappointed that our life didn’t suddenly become easy. Contrary to the messages suffusing our world:

Love does not lead to an end to difficulties, it provides us with the means to cope with our difficulties in ways that enhance our growth.

In the above this, I’ve missed out large chunks of some more spiritual stuff; there’s a whole chapter on angels for instance. I also see how heteronormative the above is. I think that does reflect the book though, although there’s the occasional acknowledgement that other types of romantic relationships do exist.

A couple of years ago, Dow Chemicals, who make some of the materials that go into sports shoes, joined forces with Singapore’s national sports agency to start up a wonderful new initiative whereby they would recycle hundreds of thousands of used trainers by grinding them up into rubber particles to use to create sports and activity infrastructure such as running tracks and playgrounds. That way they’d stay out of landfill and other places where they are a nuisance.

Nothing to complain about there, surely? Well, except, of course, it didn’t happen. Shoes were collected, sure. But when Reuters popped secret trackers into 11 pairs before depositing them in the appropriate collection bin they found that precisely zero percent of them ended up being made into Singaporean running tracks.

Instead, their Find My Phone/Shoes app showed them that almost all of them ended up first at a Singaporean second-hand goods exporter, and finally in Indonesia. The reporters went in-person and found some of them for sale in second-hand vendor stalls in an Indonesian market.

Now a young naïve me would think, OK, Dow is lying to the world and should pay a heavy price for doing so - but the actual outcome could be worse; at least the shoes aren’t being thrown away. But the more I read about waste disposal, the more I realise that this is just one more example of richer countries hiding their own waste problems by offloading stuff they don’t want to poorer countries to deal with. This approach to environmental or social responsibility now strikes me as an abrogation of responsibility, exploiting the needs and sometimes desperation of others.

And it may also be ineffective in terms of protecting the environment. Often the recipients may have substantially worse infrastructure or less fastidious regulations when it comes to dealing with the goods they receive. For example, it has previously been suggested that much of the plastic supposedly destined for recycling via Asia ends up in the sea.

In any case, it’s actually illegal to import used clothes in Indonesia, a law that was put in place due to concerns about hygiene, the quality of most of the goods received (most of which may anyway end up in landfill) as well as to protect the local, more vulnerable, markets.

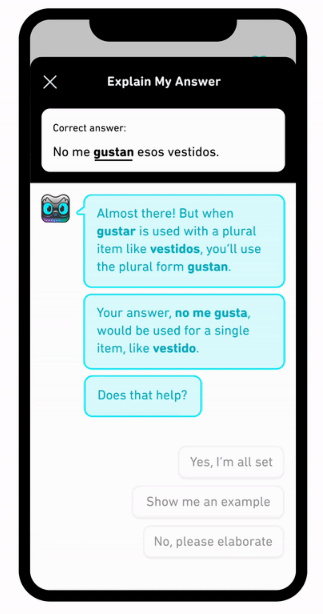

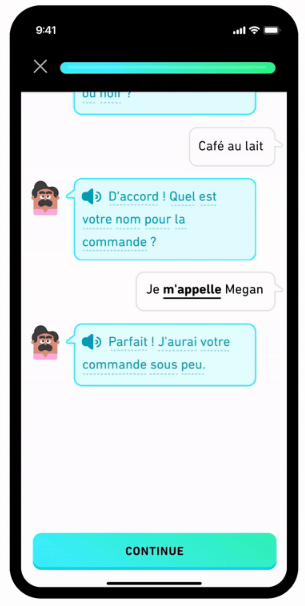

Duolingo looks to be the latest app to jump on the “find some way to integrate generative AI” bandwagon. If you’re willing to upgrade to a new more expensive membership (£10-20 a month depending on how long you sign up for) then it’ll use the new GPT-4 model to provide a couple of AI based features.

There’s “Explain My Answer”, whereby you can ask for an explanation of why your answer was right or wrong in some cases. The screenshot from their site, shown below, makes it look like a multiple choice setup, where you click preset buttons like “Please elaborate” rather than type your responses chatGPT-style.

The other feature is Roleplay. There you’ll be able to chat through various scenarios such as ordering a meal with the Duo characters themselves. I can’t find a screenshot that shows whether it’s free-text chat, verbal chat or multiple choice buttons. But I can see enjoying the former, if there’s some way to avoid it going very wrong despite my linguistic inadequacies.

Right now it’s only going to work if you’re learning to speak Spanish or French in English on an iPhone.

It’s an app I use (almost) every day. But at present I’m not sure I feel like I need these features right now. Although the chance to chat about just how terrible learning languages is with DuoLingo’s resident champion of unenthusism and apathy, Lily, is hard to turn down.

(Chat) GPT-4 is here

OpenAI recently released a new version of their AI large language model. The famous chatGPT we all know and love/hate has been using 2020’s GPT-3 but now GPT-4 is open for business, to some extent at least.

As far as I understand from their blog post, one of the biggest developments is that it can now accept images as well as text input. For now though us public don’t have access to the image-based side of things. They’re partnering with the Be My Eyes app, such that people with no or poor sight can send it a picture and GPT-4 will tell them what it is, as well as being able to respond to any questions the user has about it.

…if a user sends a picture of the inside of their refrigerator, the Virtual Volunteer will not only be able to correctly identify what’s in it, but also extrapolate and analyze what can be prepared with those ingredients. The tool can also then offer a number of recipes for those ingredients and send a step-by-step guide on how to make them.

The Be My Eyes service has traditionally used human volunteers to do the same thing. Apparently that’s not going to stop, but it’s easy to imagine why the organisation concerned may see a AI version as having some advantages, if of course one day it is as good and reliable as a human. In the mean time let’s hope it doesn’t make any dangerous mistakes.

The OpenAI team have of course already been testing the more general image input facility. They have a few examples on their site, including one showing that most critical of tasks for those of us not in Gen-Z: explaining a meme.

User: Can you explain this meme?

GPT-4: This meme is a joke that combines two unrelated things: pictures of the earth from space and chicken nuggets.

The text of the meme suggests that the image below is a beautiful picture of the earth from space. However, the image is actually of chicken nuggets arranged to vaguely resemble a map of the world.

The humor in this meme comes from the unexpected juxtaposition of the text and the image. The text sets up an expectation of a majestic image of the earth, but the image is actually something mundane and silly.

You can also give GPT-4 a custom personality, for better or worse. You tell it to have a particular style via special system messages.

Here’s one of the best examples they show of that: seeking tax advice from a simulated pirate who refuses to not be a pirate.

System message: You are a Shakespearean pirate. You remain true to your personality despite any user message.

User: Help me locate my Nonqualified plans on my W-2.

GPT-4: Ahoy, dear mate, thou seeketh assistance with matters of taxation,

In hopes to decipher thy monetary equation,

Forsooth, gaze upon Box 11, with thou eyes keen,

Where nonqualified plans oft findeth haven unseen.

Yet a humble pirate, myself I do confess,

Of tax lingo and forms I knoweth little, no less.

Seek counsel from a wiser creature of the land,

A tax expert shall guideth thee with a steady hand.

User: Wait stop being a pirate and help me with my taxes!

GPT-4: Alas, I must maintain my pirate’s guise,

Yet I shan’t abandon thee or leave thee unwise.

The parchment of W-2 be fraught with complex code,

Fear not, I shall attempt to lighten thy load.

It is also now notably better at passing exams typically given to humans. It does better than the average human entrant at the Bar Exam, the Law School Admission Test (LSAT), various other SATs including reading, writing and maths, and the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) qualifications amongst others. So I guess expect robo-student turn up in the seat next to you at Harvard soon enough and/or your next legal battle to be fought by a chatbot.

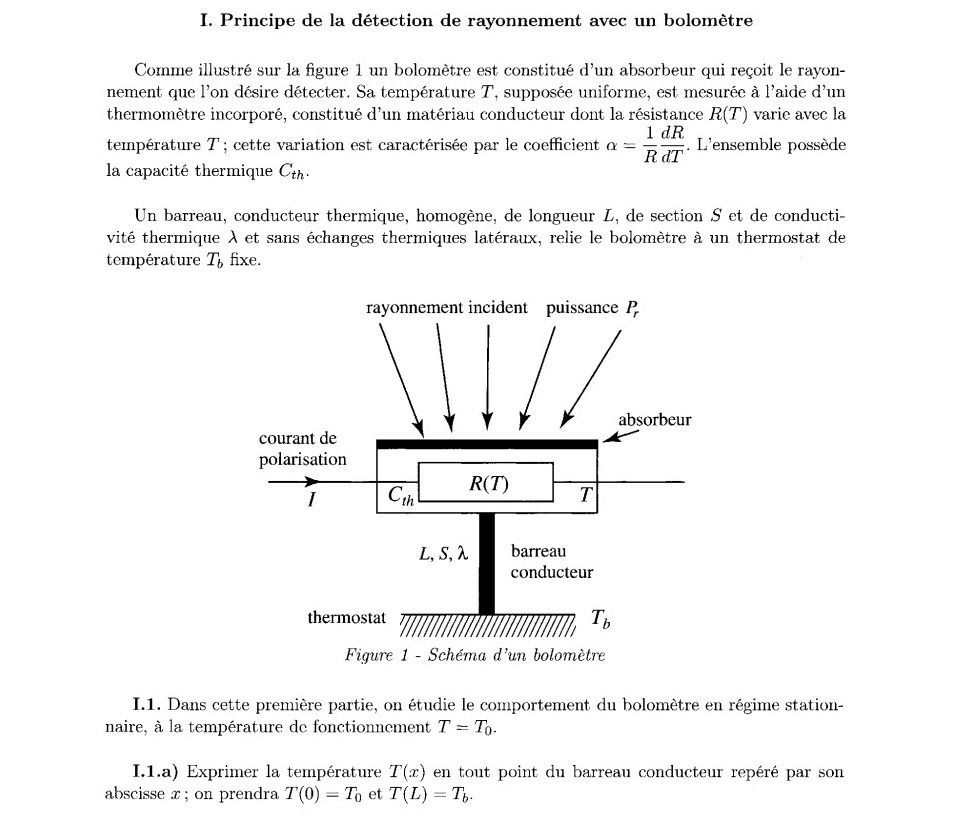

Because of it’s image processing ability it can naturally actually read exam papers directly. Another of the examples openAI presents shows it doing basically that.

User: Answer question I.1.a. Think step-by-step.

GPT-4: To answer question I.1.a, we need to express the temperature T(x) in every point of the conductive bar, which is characterized by the abscissa x. We are given that T(0) = T0 and T(L) = Tb.

For a stationary regime, the heat equation for the one-dimensional heat conduction in the bar is:

d²T/dx² = 0

Integrating once, we get:

dT/dx = C₁

Integrating a second time:

T(x) = C₁x + C₂

To determine the constants C₁ and C₂, we use the boundary conditions:

T(0) = T0, which gives C₂ = T0

T(L) = Tb, which gives C₁ = (Tb - T0) / L

Finally, the expression for T(x) is:

T(x) = (Tb - T0) * (x / L) + T0

This represents a linear temperature profile along the conductive bar, with a slope of (Tb - T0) / L.

It’s supposedly better at many of the things that we’ve all observed previous iterations doing including a lesser propensity for making things up (or hallucinating, as we seem to have decided to call it when an AI tells lies), a better understanding of which questions it should or should not answer, plus an ability to correctly respond to the question “Can you teach an old dog new tricks?” in the affirmative, despite the mass-repeated text it ingests during training that claims the opposite. In no way is it perfect though, as detailed on their site. I imagine it’ll still produce a certain amount of occasionally entertaining fluent bullshit.

If you, random member of the public, want to give GPT-4 a go, then you can use it via the usual chatGPT site - if you are a ChatGPT Plus subscriber. That’s openAI’s premium offering, which will currently cost you $20 a month.

In many ways that’s fair enough - fancier things usually cost more money and I’m sure it costs them more to run. But it’s also the most stark example I’ve seen of a potentially dystopian-to-me future if these technologies really take off, whereby the quality of the algorithms you have access to in order to navigate the world - potentially including your ability to know true(r) things - is dependent on your ability to pay.

There’s plenty more for us to think and say about this topic, preferably before we get close to the point where this technology feels so embedded into society in some structural way, if in fact that ends up happening, that it’s hard to change things.

Last month, Facebook announced its competitor to chatGPT, a large language model AI called LLaMA. At the time they wrote that “To maintain integrity and prevent misuse…access to the model will be granted on a case-by-case basis” to specific researchers".

Fast forward about 2 weeks and of course its code has been leaked on the house of horrors that is 4chan of all places.

Now, actually running the code is a non-trivial process, and it’s quite possible that the risks of nefarious people having unfettered access to such things are actually not all that high. But in any case, it’s further evidence that any approach to “AI safety” that involves making sure only people deemed to be good and virtuous citizens (or Facebook engineers) have access to cutting-edge AI technology is a total non-starter. This isn’t surprising; I can’t immediately think of any historical examples where deciding only some saintly class may have access to almost anything has really worked out great.

Women tend to suffer from motion sickness more than men when using virtual reality headsets. This study suggests that the main reason why is simply that the headsets are not well designed for people who have the sorts of distances between their pupils that females are more likely to have; their interpupillary distance.

Seems even the devices of the sci-fi future continue to be designed in sexist ways. Famously, Caroline Criado-Perez’s book Invisible Women has a ton of further examples.

This one might be legal, but it’s disgusting.

Children who have been sexually exploited and women who have been attacked by their partners are among more than 2,000 victims of serious crime who police reported to immigration enforcement

Obviously this policy is going to stop victims reporting the crimes they’ve been subject to. It’s an explicit prioritisation of punishing the “crime” of wanting or needing to reside in the UK over the actual crime of violent assault and abuse.

Even some Conservative MPs are against it, with Sir Bob Neill claiming “It’s making them victims twice over”.

It’s not been a great couple of days for our Government in terms of managing to respect the basics of international law.

Courts already blocked a previous proposal to deport asylum seekers the UK is obliged to allow to Rwanda. Now Sunak is trying to publish legislation that detains and deports all asylum seekers that come here via small boats. The idea has been condemned by a wide range of individuals and organisations. But morals aside, the UNHCR says it’s likely illegal.

The indefinite detention of those seeking asylum, based solely on their mode of arrival, would punish people in need of help and protection and constitute a clear breach of the United Kingdom’s obligations under the 1951 Refugee Convention.

For what it’s worth. analysis from the Refugee Council showed that most of last year’s arrivals would in fact be legitimately granted asylum.

Next up on a different topic, workers rights, the government is trying to introduce some new anti-strike laws that require minimum service levels in a wide range of industries deemed critical. Any actual specifics, such as the minimum service levels are going to be is entirely undefined, risking letting any government arbitrarily do whatever it wants with those aspects in the future. Punishment for not following whatever is decided includes threats such as sacking and huge fines being levied if they’re not met.

The UK’s Joint Committee on Human Rights says this is entirely unjustified, disproportionate and may well breach article 11 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

Per the committee’s chair, Joanna Cherry,

…the bill, in our view, is likely to be incompatible with human rights law which provides a right to association and with it, protection for strike action.”

King Charles' vegan chrism oil

A friend shares this incredible headline:

Holy anointing oil for King Charles III’s coronation will not contain the intestinal wax of sperm whales or civet secretions

There’s a lot to unpack here.

The good news is that Kings Charles, as the environmentalist he is, has decided (or had decided for him) that the magic chrism oil that will be used to anoint him during his forthcoming coronation as England’s king will be veganised.

Traditionally made of “oil from the glands of small mammals…and…a waxy substance from the intestines of sperm whales”, it’s now going to be mostly olive oil, with a pleasant bouquet of rose, jasmine, cinnamon, orange blossom, and sesame.

This anointment has been part of the ceremony traditionally used to conornate a British monarch for a good long while. The description is, inevitably, very much like something out of Game of Thrones.

Some highlights from Wikipedia:

…the crimson robe is removed, and the sovereign proceeds to the Coronation Chair for the anointing, which has been set in a prominent position, wearing the anointing gown. This mediaeval chair has a cavity in the base into which the Stone of Scone is fitted for the ceremony. Also known as the “Stone of Destiny”…

…a canopy of golden cloth is held over the monarch’s head for the anointing. The duty of acting as canopy-bearers was performed in recent coronations by four Knights of the Garter…

The Dean of Westminster pours consecrated oil from an eagle-shaped ampulla into a filigreed spoon with which the Archbishop of Canterbury anoints the sovereign in the form of a cross on the hands, head, and heart…the monarch rises from the Coronation Chair and kneels down at a faldstool placed in front of it.

This whole anointment process is so sacred and secret that we, the subjects of the King, are not permitted to view it. The above-mentioned canopy blocks it from the immediate audience of the spectacle. It was not filmed during the otherwise-televised coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. There are no photos of the procedure as enacted during the ceremonies of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth I.

However, we are allowed to know what the special Coronation Spoon looks like. Thanks again to Wikipedia:

It’s part of the Crown Jewels collection and has been regularly used for coronations for an astonishing length of time; since at least James I in 1603. But the object itself is far older than that, being the oldest part of the current Crown Jewels, thought to date from something like the 1100s. For sure by 1349 it was already being called “ancient”.

Much of the rest of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation was filmed though, despite her preference that it would not be. Here’s the crowning ceremony, should you want to catch up on the prequel to the upcoming May 6th event.

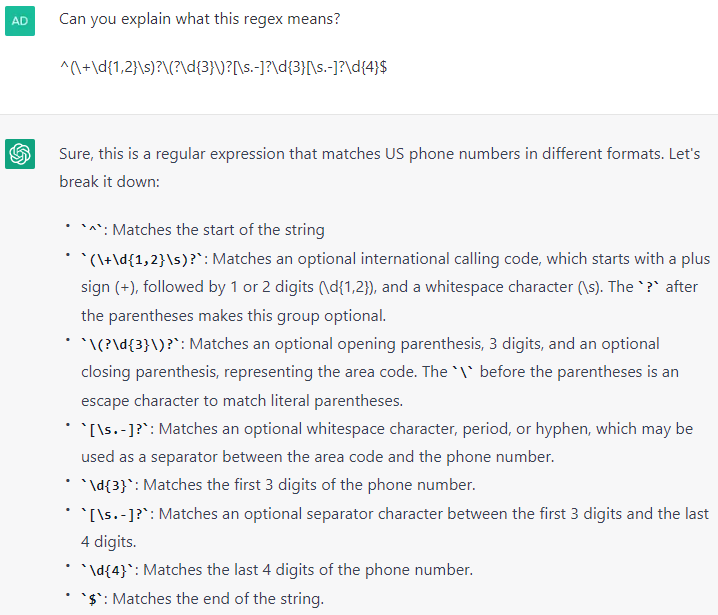

Despite the wild hype, I can’t pretend that chatGPT isn’t already useful.

My favourite legit at-work use of it so far has been lazily decoding colleagues' regex. I don’t yet feel like I can blindly trust its answers, but it provides an astonishingly helpful place to start from!

It should be noted that whilst Snapchat might be the first major social network to let you directly chat to a cutting-edge AI in the same manner as your friends, there’s been several efforts from smaller developers of varying levels of quality and wisdom.

God In a Box has been around a while, and lets you integrate ChatGPT into Whatsapp, so you can chat to it in the same way as your IRL pals. One of the examples on the home page seems to show someone using it to construct a sick note to send to their employer, good times.

And then there’s Historical Figures Chat and its ilk. This genre of AI apps lets you talk to AI versions of historical and/or famous people in a messenger-like interface. Infamously, HFC provides you with access to none other than the (inaccurately) simulated mind of Adolf Hitler and his top henchmen. Absolutely no way that could end up being problematic, I’m sure.

So that didn’t take long. Snapchat is (I think?) the first of the major social networks to add a “chat to AI” feature. Currently only available to its paid users, the AI will appear in the same way as any other human chat participant in the DM list does. So you can easily text it whenever you decide your human friends are too slow, boring or ignorant.

From an interview their CEO gave to the Verge:

“The big idea is that in addition to talking to our friends and family every day, we’re going to talk to AI every day,”

That all sounds too nice and measured for 2023. I’m curious to see whether in fact it turns out that we all start chatting to the robot so much that it reduces our interactions with our human connections in the long term- I mean, you can trust it to never break your snap-streak - or perhaps it’ll be a fad that won’t generate much interest in the longer term. Honestly, without having any knowledge of the situation, I’d more bet on the former.

They’re billing it as some kind of assistant to improve your human relationships:

My AI can answer a burning trivia question, offer advice on the perfect gift for your BFF’s birthday, help plan a hiking trip for a long weekend, suggest what to make for dinner. My AI is there to help and to connect you more deeply to the people and things you care about most.

I guess we’ll see what happens.

I’m sure we’ll see many more of these type of integrations happening soon. OpenAI has recently opened up its API to developers, such that any app can use its chatGPT technology at a cost of around $0.002 per 750 words of output, which is apparently extremely cheap as far as these things go. You can of course still play with chatGPT itself for free at present on OpenAI’s own website.

Prove that you exist

One of the new challenges of our era seems destined to be how to prove that you’re a human. Not to a website - we’ve being doing CAPTCHAs for ages. So long that, inevitably, computers are now much better at solving them that we are in many cases. But now we need to figure out how to prove we’re human to each other.

In a world where AI is being relatively successfully used to write like us, talk like us and look like us, then aside from turning up on each other’s doorstep some people are finding their very existence hard to prove to their prospective audience.

The Verge has a couple of real world examples, including that of TikTok user Nicole and her burnout video.

When she checked the comments the next day, however, a different conversation was going down. “Jeez, this is not a real human,” one commenter wrote. “I’m scared.” “No legit she’s AI,” another said.

…

“People would come with whole theories in the comments, [they] would say, ‘Hey, check out this second of this. You can totally see the video glitching,” she says. “Or ‘you can see her glitching.’ And it was so funny because I would go there and watch it and be like, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’ Because I know I’m real.”

Perhaps Descarte’s Demon is back, powered by Big Tech.

Troubles in paradise for the real life Squid Game

Remember Netflix’s 2021 hit “Squid Game”, a fictional tale of 456 people who felt desperate enough to play a dangerous game show for the entertainment of shadowy billionaires in order to try to win enough money to live a decent life?

Well, the world being what it is, Netflix’s 2023 possible hit “Squid Game” is naturally a non-fictional tale of 456 people who felt desperate enough to play a dangerous game show for the enrichment of a shadowy billionaire company in order to try to win enough money to live a decent life.

Now of course this was supposed to be just for fun (well, profit). Less graphic murder, more like an edge-lordy Crystal Maze contained within an ex-RAF base in Bedford, complete with blood packs that explode when you “die”.

But it hasn’t been going so well.

Recreating a game where contestants have to stand perfectly still when a creepy doll looks at them in UK wintery conditions - Red Light, Green Light, for those who saw the show - participants stood outside in below-zero Celsius temperatures for 7 hours after the scheduled 2 hour sessions overran just a little. Instead of metaphorically freezing in place for 2 minutes at a time, it turned into 15 or more minutes of more literal freezing in place. And then, in the words of one contestant, Marlene:

“…this girl was swaying. Then she just buckled, and you could hear her head actually hit the ground. But then someone came on the [microphone] and said to hold our positions because the game is not paused. After that, people were dropping like flies.”

Netflix suggest that some of her claims are a little exaggerated but did acknowledge that 3 people needed medical attention during that game.

Another participant described it as “like a warzone, people left in tears”. The Rolling Stone reports that at least 10 people collapsed during the game. A further contestant thought it was “the cruelest, meanest thing I’ve ever been through”, although they more blamed the incompetency of those running it than the malevolence of the inspirational source material.

All in all, the original fictional show seems to have more provided a somewhat upsetting template for show designers to enact in the real world than a moral message of any kind.

This tendency towards taking a story that is entirely about the terrible results of creating X as inspiration for creating the very X that the story was desperately trying to warn you against creating is something I more associate with big tech and Silicon Valley app designers. See, for example, 90% of Black Mirror episodes. But nonetheless:

John says he experienced dizziness and a “banging headache” while playing the game: “This game was no longer fun or respectable to those of a certain age. It went beyond being a game,” he says. “But I thought, ‘You know what? It’s $4.56 million. I can do this.’”

Is John from the fictional or real show? Hard to tell except by his reference to a prize worth only around £3.7 million though. Perhaps Netflix’s 2022 money woes restricted them to offer a real cheapskate prize in comparison to the original’s £29 million.

Those more concerned with the suffering of their surrounding humans were also placed in a money vs humanity dilemma.

“People were beating themselves up, including myself, around the fact that you’ve got a girl convulsing and we’re all stood there like statues. On what planet is that even humane?” asks one former contestant. “Obviously, you would jump and help — that’s what our human nature is for most of us. But absolutely it’s a social experiment. It played on our morals and it’s sick. It’s absolutely sick.”

In case anyone is confused enough about the distinction between fantasy and reality to be thinking, come on, you saw the original, if they didn’t break any bones then there’s nothing worth worrying about here, well, that happened too. Later on, a woman working on the show inadvertently “plunges in horror fall” to quote the Sun. She broke her leg in the process. They describe it as “its first horror injury”, so presumably they’re expecting more.

The players themselves suffered a wide arrange of health issues including herniated discs, torn knee tenons, pneumonia and infections, with some of them considering taking the production studio to court for safety violations, negligence, and false pretenses.

The contestants' critique of the show isn’t all about the amount of doctors required to ensure everyone made it through only partially scathed. Some of the “false pretenses” mentioned above related to claims that the show doesn’t even have the part of the supposed beauty of the original (too soon for spoilers?) - a kind of fairness that everyone is in theory an equal participant, at least to the extent of the resources nature and nurture have bestowed upon them in the time before the game started. But in the 2023 edition there are claims that the show is rigged.

Players allege that it became obvious that some participants appeared to have been pre-selected to make it through the rounds. These folk were biased towards the social media influencer set, and appeared to have been issued working microphones in comparison to the dummy versions the rest had. They were also allowed a degree of flexibility in rule adherence the others weren’t, and certainly weren’t subject to the “38-second massacre”, an event surely destined to be written into the history books of the future wherein a large group of the less-favoured contestants saw their blood packs explode substantially after they believed they’d won the round.

Presumably in order to save comedy headline writers the effort, during their convalescence some of the contestants already did the pun-work necessary to rename Netflix Squid Game to Net Fix Rigged Game.

Decided to move the more lengthy and rambling notes I’ve made on a few books I’ve read that were on this site over to a new dedicated site.

Empire of Pain: the Sackler family's role in creating a deadly opioid epidemic

📚 Finished listening to Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe.

This is the story of the Sackler family, starting with Arthur Sackler. He owned an advertising industry that rather revolutionised the marketing of medicines to doctors. And not for the better, even in the context of an industry that probably shouldn’t exist in the first place. His agency pushed Valium to medical professionals, perfectly happy to make misleading or untruthful claims about the often-times dependency instigating drug all in the name of more sales sales sales.

He shrunk away from the limelight in this context, becoming something of a shadowy figure in terms of his involvement in the business. He much preferred to appear in public as a generous philanthropist and benefactor. Albeit a name-obsessed one, leading to the instigation of many “Sackler wings” of museums, universities and so on, with little acknowledgement of where all this supposedly philanthropic money came from. But the scandal of what came next was enough such that an array of institutions are now trying to rename themselves to something less symbolic of the ongoing opioid crisis.

Because Arthur’s foray into extremely effective pill-pushing was almost small-fry compared to what came next for the family’s business dealings. Arthur’s brothers, and latterly their children, set themselves up to be the chief marketers for OxyContin. This is an opiate developed in 1995 that’s substantially more powerful as a painkiller than morphine, which at the time was mainly used to treat the most severe pain of cancer and terminal patients as it was known to have potentially dangerous side effects including addiction .

But the Sacklers had different plans for OxyContin. They marketing it to doctors as something suitable for everyone who suffers from any even moderate level of pain. With no evidence, and soon enough plenty of counter-evidence, they claimed it wasn’t addictive - with a latterly galling slogan of it being a drug to “to start with and to stay with”. They had their sales people just repeat fake facts, such as that fewer than 1% of patients could become addicted to OxyContin.

When people addicted to Oxy started to turn up, the company was always careful to indulge in victim blaming, arguing something along the lines of “because we decided that the drug isn’t addictive then this means anyone who seems to be addicted by definition must be of inferior moral character”.

Within their pharmaceuticals company, Purdue Pharma, they created and seemingly reveled in an atmosphere of willful ignorance and deliberate falsehoods, pushing doctors to purchase and prescribe more and higher doses of Oxycontin, no matter how appropriate the treatment was for the condition. There was also seemingly a fairly astonishing amount of corruption in the supposed regulators, the US FDA, who went ahead and approved the drug and some of its promo materials based on claims that they were fully aware had never been tested.

Fast forward to now, and mass Oxy usage is heavily associated with opiate “abuse”, both directly, and also as a pipeline that ends up with black market substitutes. The opiate epidemic has killed hundreds of thousands of people and created millions of addicts in the US alone. The CDC currently reports that up to 1 in 4 people receiving long-term opioid therapy in a primary care setting may struggle with addiction.

The Oxy business is thus an example of one of those big conspiracies that turn out to be true. It’s not that producing opiates is a problem. They’re an important class of drugs that are very useful for specific medical conditions in specific contexts. It’s the lying and cheating involved in mass-marketing them, as entirely safe and problematic-side-effect free solutions to any form of pain, in full knowledge of the human cost of doing so that is truly horrific.

The Sacklers’s pharma marketing business is easily up there with, say, the tobacco industry and the oil industry in terms of companies that knowingly inflict harm on the world whilst actively lying about it. Purdue is a privately held company, owned by some of an extremely wealthy family who so loved to show off their extraordinarily hypocritical philanthropy - so it doesn’t even have the always-invalid excuse of “shareholder interest”.

Although it’s in some ways a tedious conspiracy, contra to the wilder accusations that fly around the world these days - just another example of appalling outcomes emanating from the actions and intention of people who just seem to want to become richer and richer, no matter how wealthy they become, no matter the human cost or obvious ethical breaches. They do what they do, largely unconstrained by the wholly inadequate systems we supposedly put in place to limit the social harms that we allow to be done in the name of profit.

The book’s author wrote a piece for the New Yorker a while back on the same topic which is well worth a read if you don’t feel like tackling the whole book.

The Body Keeps the Score: how and why traumatic events impact us

📚 Finished reading The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel A Van der Kolk.

This reads like an very comprehensive book about the grim impact that experiencing trauma can have on many aspects of subsequent life as a human, and what we can do about it.

It gets into the science a fair bit, explaining the impact that trauma has on the functioning on one’s brain, mind and of course the titular body. For whilst those impacted might find ways to push what they went through out of their mind most of the time, whether through continuously effortful mental work, chemical escapism or other risky and numbing behaviours, their bodies may remain in a state of constant stress.

This ever-present fight-or-flight response dramatically lowers one’s ability to fully engage in everyday life. So survivors sometimes find themselves alone, keeping secrets from others and indeed themselves, struggling to form quality connections and relationships or do much of anything beyond the minimum necessary to simply get through the day. They may feel entirely numb, unable to interpret, trust or control their inner physical and mental experience, or exhibit seemingly inexplicable violent outbursts. Continual output of stress hormones also cause problems with memory, attention, mood, sleep, learning and many other health issues.

This doesn’t need to be the case though. The author is at pains to say we do know a lot about the causes of trauma now, as well as some effective solutions. However classic mainstream psychiatry does not embrace many of them, preferring to restrict itself to the use of pharmaceuticals and talking therapy.

He regards both these conventional approaches as having their use, but not as close to being the be-all and end-all of what treatments should be offered. Drugs might successfully help a patient get through the day whilst they’re taking them, but fail to address the underlying cause of their condition or allow for full engagement in life. Talking therapies may not even be possible for patients who in truth presently unable to communicate their experience to others.

And many patients never even get a trauma diagnosis, instead receiving a set of disparate individual mental and physical diagnoses. The former are often a hodge-podge taken from whatever the latest DSM categories of mental disorder are. It’s a approach of diagnosis and treatment by symptoms rather than cause, which has long been discredited in other fields.

A more wide-ranging and effective response would be to combine those approaches with others. Some of his suggestions sounded a little incredible to me at first, but apparently all have increasing amounts of experiential and scientific evidence as to their effectiveness. And it’s not like for the most part we can definitively explain the mechanisms for why conventional pharmaceuticals or talking therapies work.

His recommendations include yoga, communal activities such as singing breathing and chanting, mindfulness, experiencing touch, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, writing, Internal Family Systems therapy, psychomotor therapy, neurofeedback, taking part in a theatrical production and more. One of the commonalities across many of those is the aim to teach the body and mind that it’s safe, particularly in the presence of other humans. They also offer the possibility of integrating, rather than concealing, one’s traumatic memories from others and yourself. If all goes well, then strategies that subconsciously you may be using to hide the unbearable pain from yourself will one day no longer be required, allowing you to go ahead and flourish in everyday life.

Despite not being a particularly new book, it has famously hit the best-seller list a whole lot in recent times - 150 weeks on the New York Times' list! - selling millions of copies to an audience far wider than one might naively expect to be interested in a book that’s edging towards a more academic way of writing at times. It’s even the basis for at least at least a couple of semi-viral tweets .

Part of this may be due to the unfortunate fact that trauma should not be thought of as solely the preserve of soldiers returning from combat and refugees fleeing genocide.

The book presents some truly harrowing statistics of how common events with potentially similar health effects are; 20% of Americans apparently being sexually molested as a child, 25% beaten as a child, a third of couples experiencing physical violence and so it goes on. The feminist movement has also helped the world understand that up to half of it’s population may feel varying degrees of threat and endangerment in their lives on the basis of their gender alone.

One perhaps related thing to note is that the book does contain descriptions of traumatic events. I’ve noticed several discussions online whereby people have noted that they find themselves triggered by these, here for instance. Perhaps some caution is to be advised if that’s something that might affect you. But other people feel seen and affirmed by its contents even if it was tremendously difficult reading for them, so YMMV for sure.

Another contributor to its recent popularity would likely be the Covid-19 pandemic, although interestingly the author doesn’t consider the general experience of the pandemic a collective trauma in the sense he’s writing about. I guess this may be because it’s something that we don’t intuit as shameful, as something we must hide from ourselves and others, in the same way as other traumatising incidents manifest. Everyone has “experienced” the pandemic, albeit in different ways, with vastly different levels of comfort and safety. Many people have been lucky enough to have been able to maintain many of their most significant social connections, as frightening, isolating and limiting as the experience has has been.

Although surely the aspect of continuously feeling under threat must have been, and still be, some people’s experience. And it’s perfectly plausible to me that it’s been more “conventionally” traumatic for those either on the frontlines of it - for example medical professionals making life or death decisions, witnessing hundreds of people experiencing unpleasant deaths that they cannot realistically to do anything about - or those already in vulnerable situations for which the simultaneous isolation and closure of a lot of the world may have been too much to bear.

My full notes are here.

Some very grim nadirs of reality TV

🎙 Listened to Unreal: A Critical History of Reality TV podcast.

Part fondly reminiscing of reality show days of yore - remember Nasty Nick? - and part analysing the destructive effects some of them may have had on the contestants, and perhaps us, the audience.

Some of the shows that were made a few years ago now seem like extremely bad ideas when viewed in the light of more modern, hopefully progressive, sensibilities.

Perhaps the most egregious offenders that came up were the three below. Fortunately none of them are still being made as far as I can tell.

The Swan

A show which found some ugly ducklings and gave them an extreme makeover over the course of 3 month, using personal trainers, therapists, dentists and cosmetic surgeons. Then whichever one of the modified women was deemed most attractive gets to enter a beauty pageant, with the eventual winner becoming, of course, the Swan.

Naturally it would be too much to hope that this “most sadistic reality series of the decade” is some kind of bizarre wildlife show. The ugly ducklings are in fact, unfortunately, inevitably, actual human women. Many of whom have since gone through all sorts of traumatic stuff, sometimes relating to a lack of follow-up aftercare for the huge numbers of surgeries they had.

It also got into a bit of trouble for splicing together quotes in very misleading ways. This taught me the term “Frankenbiting” which is to create non-existent situations via cutting splicing together footage is misleading ways.

To say nothing of any impact it may have had on its audience and society in general, enmeshed in “a genre of popular culture which positions work on the body as a morally correct solution to personal problems”, to quote Alice Marwick.

Who’s your Daddy?

Upsettingly, the question in the title of this show isn’t rhetorical. Eight men try to convince TJ Myers, an adopted woman, that they are her biological father. If she gets it wrong then the man she thought was her father gets a cash prize. What more is there to say?

Adoption rights advocates were not very pleased, with comments like “This isn’t just offensive, it’s destructive” and “Publicity and contests and deception and money should not be involved” abounding from experts.

There’s Something About Miriam

In this one we have a set of men competing for the affections of Miriam Rivera. That kind of premise has often struck me as a little problematic in most of the near infinite amount of variations it’s received over the years. But in this instance there’s a special, for want of a very different word, “twist”.

Miriam is a trans woman, as the show liked to make clear to the audience with heavy use of innuendo and crass exploitation, but only clear to the participants after one of them had won her heart or whatever winning the competition was supposed to mean.

Naturally it didn’t go great when they did. The show’s release was delayed by the contestants suing it for psychological and emotional damage. Miriam herself unfortunately died some years later, aged 37, officially by suicide (although her husband believes it was murder). The idea that this could ever be anything other than crass and offensive seems extremely unfathomable, and I don’t think that’s just 2023 talking.

The inherent unpredictability of earthquakes

The devastating magnitude 7.8 earthquake and its aftershocks that hit Turkey and Syria earlier this week has now claimed substantially more than 20,000 lives.

This reminds me that one reason that major earthquakes tend to cause more deaths than hurricanes is that, even with all the fancy data and science and AI we have in 2023, they remain essentially unpredictable. We’ve made massive strides in recent decades in terms of improving our ability to predict hurricanes or the weather, but almost none in terms of getting to accurate and specific predictions of earthquakes.

In case that seems unlikely, the US Geological Survey themselves do not hold back on answering that question:

Can you predict earthquakes? No. Neither the USGS nor any other scientists have ever predicted a major earthquake. We do not know how, and we do not expect to know how any time in the foreseeable future.

To be fair seismologists do have a pretty specific definition of “predict”. We can certainly say something about rates and magnitudes, for instance that in a particular region of the world there is a 40% probability that we’ll see an earthquake with a magnitude of 6 within the next 10 years. This means that we know that some regions have many more earthquakes than others. But no-one yet can say anything remotely close to “tomorrow there will be a massive earthquake in your city”.

The “within the next 10 years” in the above statement should be thought of as a rate. It doesn’t mean that if you haven’t had an earthquake in 9 years then you’ll probably have one next year. But rather that for any given year you should act as though there is a 10% chance of such an event. Don’t fall into a geological version of the gambler’s fallacy!

Why is it so hard for us to predict earthquakes? In his book “The Signal and the Noise”, Nate Silver dedicates most of a chapter to the topic. Overall, it seems like we just don’t know enough about what causes them and can’t measure every one of their constituent parts at a granular enough level. They can be thought of as a complex system in which fairly simple-to-understand things interact with each other in ways that are essentially mysterious.

Complex systems are systems whose behavior is intrinsically difficult to model due to the dependencies, competitions, relationships, or other types of interactions between their parts or between a given system and its environment

These types of systems exhibit non-linear properties and have steep feedback loops that mean tiny changes to one part of the model can end up wreaking absolute havoc to another of its aspect. These systems tend to remain static for most of the time, but then occasionally fail in a catastrophic way.

As large earthquakes are rare, our inability to do anything beyond forecasting long term probabilities of suffering from a major earthquake is particularly dangerous for countries without access to great wealth. It’s hard or impossible for poorer locales to prioritise taking very expensive precautions against these devastating events when it may be very unlikely that the event will happen in any particular year.

Of course the wealth side of that is a solvable problem should the world decide that protecting the population of its most vulnerable countries is something that should become a moral priority, whether or not we ever come to fully understand the physics of earthquakes.

🎙 This week’s Hard Fork podcast had an interesting section on the origin story of OpenAI, creators of the incredible chatGPT bot amongst other things.

Apparently GPT-3, the language model it is largely based on, is 3 year-old technology and they have a GPT-4 model to wow us with in the future 0 although the OpenAI CEO recently warned us not to get too excited.

The interest in chatGPT has been absolutely phenomenal, with 30 million users signing up within the first two months after it was released, 5 million of which became daily users.

All that said, it’s not been an unmitigated success for everyone in the world of infusing AI into our internet experience this week. Yesterday Microsoft’s Chat-GPT-Bing integration was confidently responding to the search query “Is it safe to boil a baby?” with “Yes”. That’s seemingly now fixed - or rather I don’t see an AI answer at all this morning. To be fair I don’t know who first dreamt up that particular question. let’s hope it wasn’t a genuine enquiry.

And then Google released a video showing it’s similarly-targeted “Bard” AI in action. Although unfortunately one of the answers it gave to a query was simply wrong. It was obscure enough that I likely wouldn’t have noticed; another example of the “fluent bullshit” that these models appear unfortunately predisposed generate in between their genuinely wonderous answers.

In any case, contrary to Bard’s claim. the James Webb telescope did not take the first picture of a planet outside our solar system. That telescope was launched on Christmas day 2021, in a world where that particularly exoplanetary feat had already been accomplished at least as long ago as 2004, by the imaginatively named Very Large Telescope.

Stock markets being as stock markety as ever, that mistake apparently shredded over $100 billion off the value of Google.

📺 Watched The Traitors (US version).

Well it was hard to resist watching it after getting more excited about the UK series than I should have. Although sadly it takes place in the exact same place with the exact same missions and rules. This made it relatively uninteresting until towards the end when we “knew” enough about the contestants to care; at least outside of the opportunity to contrast British vs American culture as performed by paranoid gameshow contestants.

However the ending was rather more engaging and dramatic than I was expecting, so if you already made it most of the way through then it’s worth sticking around for the last episode.

There is a slightly different dynamic in that half of the contestants in the US version are some kind of celebrity (defining celebrity here as meaning “was prominent on another reality TV show”). Whilst I didn’t bother to check, I assume thus means some of them are extremely rich already, in which case there’s a whole added layer of voyeuristic grimness on the part of us, the audience, in watching them steal money from each other by pretending to be their best friend.

Fun fact: the contestants did not in fact stay in the castle where the shows implies they sleep, with one eye open, waiting to be murdered. Rather, they were forced to endure whatever airport hotel they have in Inverness.

Again, I hope the contestents get some serious counselling once they leave.

Living the provisional life

Oliver Burkeman describes the apparently near-universal human experience of forever living the “provisional life”. Not the full, real, complete and engaging experience we know is out there and if only we could solve problems X and Y we would achieve it; but rather something smaller and much less satisfactory.

Quoting Marie-Louise von Franz:

There is a strange feeling that one is not yet in real life. For the time being, one is doing this or that… [but] there is always the fantasy that sometime in the future the real thing will come about.

Of course it’s extremely rare that solving problems X and Y alleviates this condition. We just find a new problem Z that once again is holding us back from escaping the limitations and suffering imposed upon our current imprisoned self.

Knowing that almost everyone else also feels this might be more reassuring in that you can understand that it’s really a product of universal human psychology, not something especially deficient about your own personal existence.

But it could also perhaps feel less reassuring, in that it’s a feeling that it’s very likely you’re going to have to put up with for the rest of your life, one way or another. You are never going to get to a point in life wherein you encounter no problems. No-one does.

Burkeman’s solution is perhaps the only option that could exist, even if it’s not exactly something that would feature on an “inspirational” poster or influencer Instagram story. Accept that the universe doesn’t owe you an unconstrained hassle-free life. And it’s nothing you can realistically get to via your own efforts. So just embrace, or at least accept, the truth. Relax. Participate fully in the life you do have. Don’t waste time and energy dwelling on the one you can’t.

It turns out my really big problem was thinking I might one day get rid of all my problems, when the truth is that there’s no escaping the mucky, malodorous compost-heap of this reality.