“The Internet” is just too big and too important to think about as being one thing these days, even if we constrain ourselves to the bits of it that are most popularly used in 2024 (RIP Gopher, Usenet et al for most people, although I suppose hello Gemini?). In considering the impact of things like generative AI, the demise of the original vision of social networks et al I’ve found it far more manageable think of the internet as being layered.

This is a very unoriginal and frosty take. But thinking about what those layers are fixated my attention for a while.

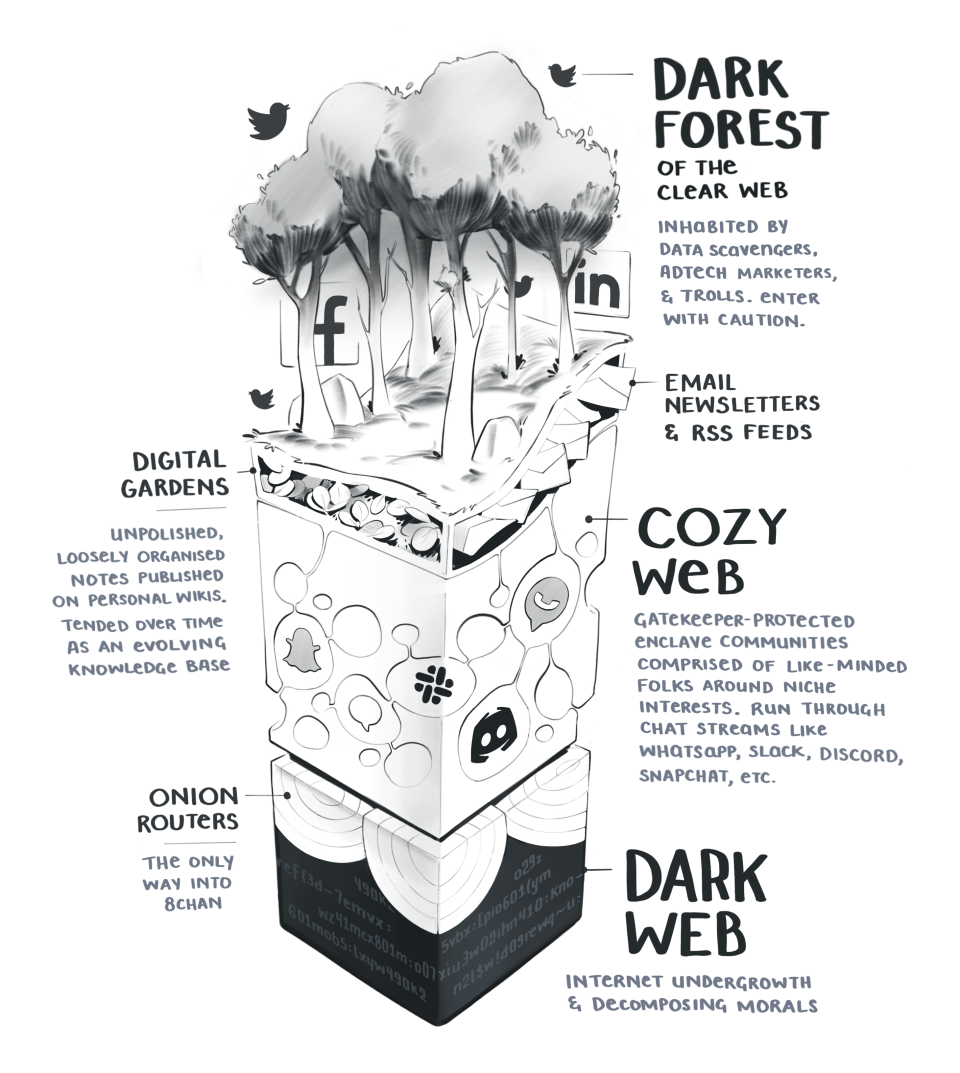

Probably my favourite viewpoint on it, and certainly the most beautifully illustrated one, is Maggie Appleton’s image of “our current social internet situation”.

At the top we have the Dark Forest of the “clear web”. These are your classic websites. The places you usually end up on if you click on the top Google search result, or indeed a lot of Google-owned properties themselves. They’re open to almost anyone with a usable internet connection. In fact they’re often desperately vying for your attention. For the most part they’d in theory be representative of an older, more utopian, vision of the internet - information wants to be free, everyone deserves an equal voice.

…now that most citizens have the tools to engage in mass communication, do more of them have a voice in public debate? Has the web made the public sphere more accessible to a greater diversity of voices?

Many of the web’s early boosters were confident that the answer was yes. Mass media conglomerates would soon dissolve and the net would give rise to an army of Davids.

The only problem is that we’ve ruined it.

From Appleton’s writing:

Most open and publicly available spaces on the web are overrun with bots, advertisers, trolls, data scrapers, clickbait, keyword-stuffing “content creators,” and algorithmically manipulated junk.

By choosing advertising as the currency that underpins the internet, and then creating algorithms optimised to focus your attention on a particular page within the sprawling morass available in an environment where quantity is more predictably lucrative than quality, we’ve ended up in a digital world with where of weirdly worded near-identical sites infused with surveillance trackers between a vomitorium of lurid adverts compete with each other to tell you which mail-order mattress you should buy, invisibly ranked by referral commission, when all you wanted to do was learn how to sleep better. Whilst human writers being replaced by very mid AI text generators is a real and important issue, let’s not forget that there are an indeterminate number of dissatified human writers who are currently paid to write for the AI algorithms in the first place.

I think most of the popular social networks, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter et al. largely fit into this bucket. Oftentimes they require you to sign up in order to access what lies beneath. But they’re generally open to all. At least all who are happy to sign away a vast and unreadable set of rights - the infamous yet ubiquitous “terms and conditions”.

Sometimes their content is indexed and algorithmically hoovered up by search engines and, increasingly, faceless AI bots, in the same way that any other website is. Other times their data is a preciously guarded hoard, unavailable to “outsiders”. But as soon as you sign your various rights away, up until the point where they decide they don’t want you there any more, it’s all there, searchable, exploitable, demanding your attention irrespective of whether you had actually planned to spend the evening watching people scream at each other about whether a school really did provide litter trays for their students who identified as cats (spoiler: they did not) or sing sea shanties.

There’s little incentive to present your whole, honest, self in these places. Your genuine interest in, say, providing a financially secure life for your family will translate to 6 months of every website you visit featuring adverts for the next shitcoin destined to pollute the planet until being rug-pulled away from anyone unlucky enough to have been suckered into the promise of a lifetime of financial freedom.

And if the algorithmised ads don’t get you, the polarised populace of the place may. No-one wants to be the Main Character. Everyone has said something in their lives that if taken entirely out of context and presented in the worst possible light is likely enough for a few million people to hate-scream at you about. And the “here’s something that will annoy you” algorithms will ensure that they are provided the chance to do so.

Why “Dark Forest”? It comes from a parallel Yancey Strickler makes to the amazing sci-fi trilogy (well, I’ve only read book 1, but it was great) “The Three-Body Problem”. In pondering on why humanity hasn’t yet seen all that convincing proof of alien life, Liu Cixin writes:

Imagine a dark forest at night. It’s deathly quiet. Nothing moves. Nothing stirs. This could lead one to assume that the forest is devoid of life. But of course, it’s not. The dark forest is full of life. It’s quiet because night is when the predators come out. To survive, the animals stay silent.

Why no alien visitors to our planet? Perhaps there are no aliens, or perhaps the inhabitants of the rest of the galaxy just know that to speak out, to make contact, invites only risk, only predation. Why is the open web seemingly populated mostly by adtech infused ‘brands’ and extremely partial views of the most theoretically enviable parts of every influencer’s lifestyle? Not because all the real people actually vanished. We didn’t actually turn into one-dimensional caricatures of ourselves. We’re just keeping much of our lives out of the reach of our perceived predators.

So many netizens have slunk away to the cozy web for some respite. The idea that large “open” - well, open only in the sense of letting everyone sign up - social networks are there to connect us with the people we know and love for the betterment of all our relationships has obviously failed. Many of those not still publicly arguing about whether ivermectin cures 5G or how bad their neighbour’s kids are have substantially shifted their focus to places that are less visible, more hidden, less able to have whatever gems of wisdom they contain brutally scraped by Google for it’s publisher-damaging, often inaccurate, “answer box”, or, in more recent times, by hungry AI bots looking for massive training data.

In this category we’re largely talking about chat services; think WhatsApp groups, Discord, or Slack. Often invite only, rarely searchable from the outer world, and - as yet - less infused by bots, humans acting like bots or optimised advertising. It feels easier and safer to build real relationships here; to say what’s on your mind, to talk to people who share your interests.

The downside of course is that they’re generally ephemeral. The wisdom you espouse, the photos of your friends, the stuff you find meaning in there is probably going to have gone, at least in a practical sense, by the time you want to revisit it in the more distant future. Random person X who would have enjoyed hearing what you had to say, but doesn’t happen to be signed up to same same channel of the same service at the same time, is probably not going to be able to. People who never knew others like them existed may never find out that they do if their dialogue is restricted to these spaces.

Information from these spaces is also hard to link to, hard to share with others. Want your friend to see part of a Whatsapp chat or a Discord conversation from a specific channel? Oftentimes sending screenshots, with the commensurate limitations of doing so, is the only practical way. Of course, those same screenshots will themselves become lost over time.

And if the service becomes unfashionable, too expensive or otherwise annoying for the company who runs it - it’s hardly impossible to imagine even the behemoth WhatsApp being shuttered one day by its owner who already had a similar-seeming product when they purchased it if they felt like they could get away with it - there’s a good chance that everything is lost. This stuff doesn’t appear on the Internet Archive. But it’s a safer place to be yourself, to reveal your inner workings, to open yourself up in.

From Yancey Strickler’s “Dark Forest Theory of the Internet":

These are all spaces where depressurized conversation is possible because of their non-indexed, non-optimized, and non-gamified environments.

In Maggie’s words:

We create tiny underground burrows of Slack channels, Whatsapp groups, Discord chats, and Telegram streams that offer shelter and respite from the aggressively public nature of Facebook, Twitter, and every recruiter looking to connect on LinkedIn.

How does it work? From Venkatesh Rao’s formative article, it’s all about very human interactions:

…the cozyweb works on the (human) protocol of everybody cutting-and-pasting bits of text, images, URLs, and screenshots across live streams. Much of this content is poorly addressable, poorly searchable, and very vulnerable to bitrot.

Between the Dark Forest and Cozy Web exists a hybrid category - information available in entirely open formats to anyone who actively requests it, but largely hidden from those who haven’t. It’s often unindexed by the web search engines and fairly inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t know that it exists. Think subscriber-only email newsletters, RSS feeds, that kind of thing. The rise of Substack and its competitors have brought email newsletters to the modern consciousness - although Substack isn’t actually the best example here, as its free newsletters are typically archived as openly accessible webpages too. But the general idea of email newsletters has probably been around for a good four decades or so.

Finally, deep below the Cozy Web, we see the Dark Web. That’s somewhere beyond the typical reach of most humans and their bot counterparts. Its content doesn’t appear on search engines. Clicking on a link in your basic default home web-browser will not get you there. Rather you’d need to get special software and/or authorisation to see it, even if you had a way of knowing it existed in the first place.

Everything’s encrypted. Anonymity is a key value - unlike visiting a surface web, a clear web, website, a darknet site does not know where in the world you’re tuning in from if everything is working well. Tor is probably the most famous of these systems. If you ever see what appear to be weblinks that end in .onion then that’s a Tor site you’ll need a (freely available, one option here - and these days easy enough to use) special browser to access.

This technology clearly has the side effect of making users very hard to police. Thus, unfortunately, much of its content is ethically or legally dubious.

Moore and Rid’s 2016 article Cryptopolitik and the Darknet included an attempt to analyse the content of thousands of .onion addresses and found that:

The results suggest that the most common uses for websites on Tor hidden services are criminal, including drugs, illicit finance and pornography involving violence, children and animals.

The most common commodity they found on sale was pharmaceutical or recreational drugs. The bulk of the finance sites were around Bitcoin-based money laundering, selling stolen credit card details, bank accounts and counterfeit currency. Let’s not spell out what’s encompassed in the third category above.

But don’t get the idea that it’s all terrible - Tor and its ilk provides a way to access information from countries that cruelly block its citizens from being able access much of the conventional internet, including from the likes of Amnesty International . Big news sites like the BBC or The Guardian have a presence. Whistleblowers can share their information with the organisations who can leverage it to make the world a better place, with a higher level of impunity. And, sad to say, some people reputedly find sourcing the drugs they need for their medical conditions easier via these unofficial channels than the methods that in-the-light society has made available to them.

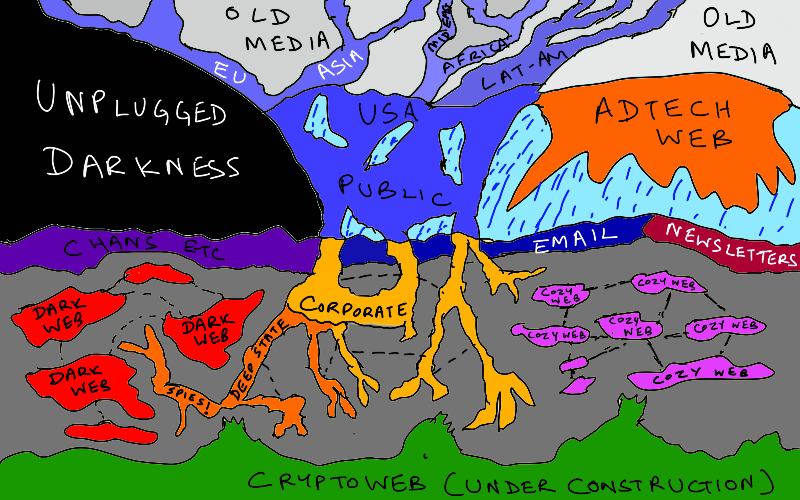

Maggie Appleton credits Venkatesh Rao for the cozy web terminology. Venkatesh himself illustrated his view of the “complexity of the extended internet universe” in what I think is his original post on the matter.

This version, whilst less aesthetically pleasing than Appleton’s beautiful illustration - but still nicer than anything I myself could accomplish - holds two dimensions within it. Imagining it as a two dimensional graph, the horizontal axis moves left to right from sites entirely hidden in the dark through to the “well-lit” conventional web on the right. The vertical axis deals with the level of security the content is held under, from entirely open at the top through to information that’s locked behind complex security technologies and procedures at the bottom.

The x-axis itself is the private-to-public boundary, marked by email for most of us. The y-axis is the high-risk to low-risk boundary, marked by security stronger/weaker than simple passwords for most of us.

There’s not a lot of stuff in the very-private very-visible top left quadrant for obvious reasons - beyond things like accidental data leaks.

Bottom left is the Dark Web, as described above. Full of private information, of secret activity, of often illicit transactions. It’s high risk stuff where privacy is essential for users to complete their goals, but stuffed behind both technological and human security systems far beyond what you’d need to provide in order to log onto Facebook.

Top right is the Dark Forest - the modern-day web, infused with business doing their best to make you see their adverts, to persuade you to buy their wares, to penetrate into your mind, into your email inbox. No security is needed to venture into this content. Everything is in dazzling light, actively pushed onto your eyeballs by search engines, advertising networks, and so on. So much is advertising funded. The more you see it, willingly or otherwise, the more they get paid.

That leaves the Cozy Web, which within this schema is situated in the bottom right. There is a certain amount of security to navigate. You need a special app (e.g. WhatsApp), an account, maybe even an invite. The content isn’t indexed by Google or forced into the faces of unsuspecting ‘X’ users (or for that matter trivially searchable by malicious X users). But when you’re in there, the chat is frequently low risk, stuff that doesn’t feel private in the same sense that your medical records do. It might be your friends' groupchat, which is mostly just all that stuff you’d banter about IRL if you saw each other a bit more, or your colleagues' thoughtstreams - the digital post-pandemic alternative to the watercooler, sanitised in the same sort of way. All in all, there’s no need or active desire to hide this area of the internet from the FBI in the heads of most of its users, it’s “boringly private” to use Rao’s description with both the benefits and drawbacks such an environment brings.