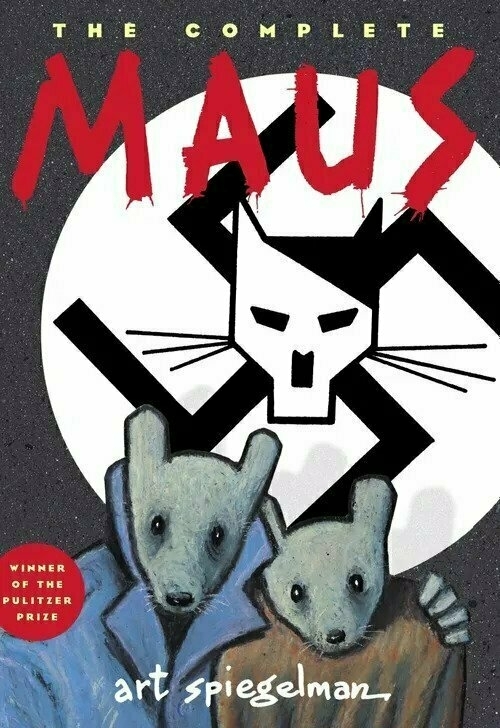

Maus: The Pulitzer-prize winning graphic novel that portrays the horrors of the Second World War

📚 Finished reading: The Complete Maus by Art Spiegelman.

This is a comic book portraying the author’s difficult conversations with his father about the father’s experience as a Polish Jew in the Second World War. Harrowingly, but far from uncommonly, the experience included time imprisoned at concentration camps, including the infamous Auschwitz.

Most of the people he knew, most of the characters in the book, ended up dying at the hands of the Nazis. They are shot, hung or, more frequently, the victims of a long, slow, tortuous death journey of absolute neglect from captors who do not see you as human.

Actually the book doesn’t portray almost anyone as human, not in literal terms. Whilst the concepts of humanity and inhumanity infuse the story throughout, visually the participants are portrayed as cartoon animals. The Jews are anthropomorphic cartoon mice. Their former gentile country people, occasionally later collaborators, as pigs and the Nazis are cats. And the language is at times rough, ungrammatical, unrefined.

Out of context this might seem to be a strange or trivialising approach to the most awful of events. But in reality the stark black and white illustrative loses none of, and perhaps draws us into, the horror of what transpired. It pulls no punches. The frank representations of what went on maintain their visceral impact.

As Spiegelman once wrote:

Maybe vulgar, semiliterate, unsubtle comic books are an appropriate form for speaking of the unspeakable

This exchange sums it up the criticisms along those lines succinctly:

“Don’t you think that a comic book about Auschwitz is in bad taste?” one angry reporter asked him when the book was published in Germany.

“No,” Spiegelman replied, “I thought Auschwitz was in bad taste.”

The father, the “hero” who survived the horrors, is a complicated character. He’s on at least his second marriage and it’s not going well. He’s miserly, grumpy, demanding, with unpleasant views, whether shaped by his experience of things no human should every experience or otherwise. He’s demanding, an incessant. His son, the author finds him hard to be around, wants to avoid him, to get away even as he becomes increasingly unwell. The book switches between the father’s story of life in the war back to the present day life and its many tensions until both are resolved, one way or another.

The book - the only graphic novel to ever win a Pulitzer Prize at the time of writing - became more famous in recent times following a ban on it by a Tennessee school board, ostensibly for its bad language and a tangential depiction of nudity. In it’s time the book has also been banned in Russia and burned in Poland.

Many people believe that the in reality the Tennessee action was nothing more than a continuation of the politically driven book-banning so favoured by the supposed freedom-loving political right of the US. At the very least, I worry about the mind and priorities of anyone who thinks the most disturbing thing about this book is the occasional mild swear words.

But it’s the sort of disturbing that is important that humanity never forgets, never thinks can only happen once, only in the past. ‘Never again, and again and again’ to quote the author.