📚 Finished listening to The Monopolists by Mary Pilon.

As far as board game creation stories go, the story of Monopoly’s invention is a well known one. Not least because for a while it was included in the contents of the game box itself, at least in the US.

For the un-initiated: Stuck at home having lost his job during the US Great Depression, Charles Darrow had a sudden flash of inspiration and invented Monopoly. Firstly to amuse his family during that difficult time in American history and latterly, in 1935, to sell to the Parker Brothers company. Darrow ends up as an incarnation of the rags-to-riches American Dream story as hundreds of millions of copies of the game were produced and shipped around the world.

The game certainly spread. In the end millions of groups of gamers would go on to learn the basics of capitalist economics, the dog-eat-dog winner-takes all majesty of the free marketplace, with the winner of each game ending up with reams of imaginary real estate and their respective virtual incoming rents from their non-propertied companions. A true simulation of the American Dream, accessible to all, realised like never before.

Except, inevitably, that story isn’t true. Monopoly wasn’t really invented by Charles Darrow. Or any other individual entirely. Like many other of humanity’s cultural artifacts, what we now know as Monopoly is a pastime that evolved over space and time.

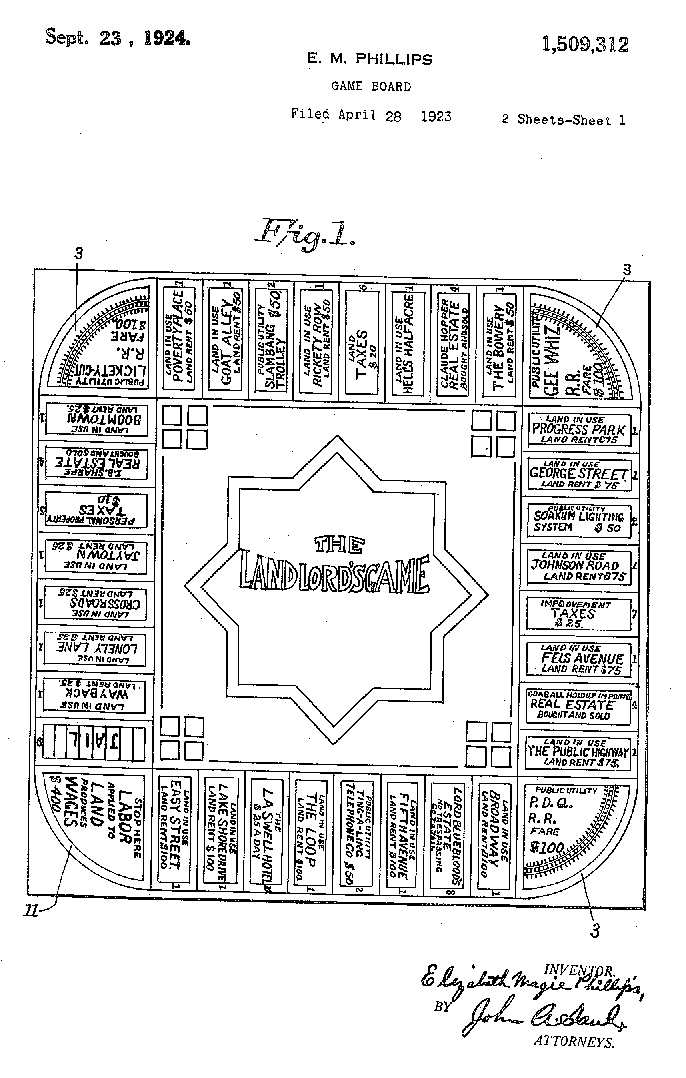

The author starts the story with the person that could perhaps most fairly be termed Monopoly’s originator, Elizabeth Magie. Born in 1866, she was very interested in both politics and inventing. This of course was certainly not encouraged for women of that era. Nonetheless, in 1904 she patented “The Landlord’s Game”.

Ironically, considering what it turned into, the game was intended to espouse her Georgist principles and demonstrate the perils of unbridled rentier capitalism; specifically how monopolies over land led to ruin, and how taxes could be used to ameliorate these outcomes. It was intended as part of a political argument against the massive concentration of land-based wealth in the hands of landlords, not a celebration of it.

In general, the Georgist movement was dead against the private accumulation of wealth from land ownership

From Wikipedia’s entry on Georgism:

…although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—including from all natural resources, the commons, and urban locations—should belong equally to all members of society

The Landlord’s Game could be played either with Monopolist rules, where players are incentivised to become monopolists and force other players out of the game - these will be familiar to anyone who has played modern-day Monopoly. But it also came with anti-monopolist rules, where the game is won only when every player has doubled their original money by virtue of communal wealth creation.

Educational as it might have been, it didn’t sell very well at the time. But it was taken up by certain communities - notably the Quakers and various socialist-leaning academic types - who passed various incarnations of the rules and materials of the game on to their nearest and dearest, sometimes adding or changing a few of the details. Over time it grew ever closer to the Monopoly we know today. Magie’s original version already had the property, railroads, utilities and jail squares familiar to us today, as well as idea of continuously circling a square board with no pre-defined end, a relatively rare setup at that point time. As it passed from hand-to-hand some of the properties got renamed and the Chance and Community Chest cards we’re familiar with today were developed.

What came next is a frustrating lesson in intellectual property law. After Darrow sold “his” game idea to Parker Brother, they went on to persuade Magie to sell them the patent to her original Landlord’s Game, misleading her into thinking that they would mass produce and market copies of it, with its original message intact, worldwide.

Well, have you ever seen “The Landlord’s Game” in a game shop? Of course not. In reality, they’d wanted to acquire the patent to protect themselves from the increasingly obvious truth that the real story behind the Monopoly game they were selling in such a profitable manner was not one that suited them.

If this book is to be believed - and it certainly seems very thoroughly researched - Darrow and Parker Brothers behaved somewhat deviously, probably fraudulently, to do their best to retain the sole right - the monopoly - to sell Monopoly based on its manufactured origin story. Whilst of course compensating none of the many other people who contributed towards the development of the modern-day institution of Monopoly over the decades.

Again layering on the irony, some of the truth of this came out as part of another intellectual property related court case, but one that Parker Brothers initiated. An economist called Ralph Anspach created a game called “Anti-Monopoly” in 1973 that was designed to help people understand the perils of real-life monopolies.

Parker Brothers didn’t like that the name involved the word “monopoly” and took him to court to prevent him selling his game. Preparing his defence led Anspach down a path of somewhat obsessive research into the history of Monopoly, with the resulting idea that Monopoly itself should be in the public domain with the copyrights and trademarks Parker Brother claimed to hold being invalid. A decade later a settlement was reached, but not before the case materials revealed a lot of the truth that Mary Pilon now, in turn, reveals to us.