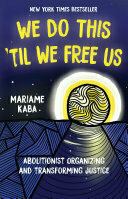

📚 Finished reading We Do This ‘Til We Free Us by Mariame Kaba.

In this book, Mariame Kaba presents a collection of short and readable articles - reprints of magazine or interviews for example - all dedicated to educating about and encouraging readers to take actions towards the total abolition of the prison system, and policing too. “Defund the police” taken to its most literal conclusion.

It’s a position I started off with some sympathy towards. I am more than happy to accept that far more people are in prison than should be. This book focuses on the US system, and that is almost indisputably true there.

I was already happy with the idea that the focus of the criminal justice system (or criminal punishment system, as she calls it - feeling there’s very little justice to be had in it today) should be on issues such as safety and restitution rather than punishment for punishment’s sake. Prison should be a last resort after all other options have been explored. There’s a lot of reform to what prison entails, and the life of someone post-prison, that should be urgently made. Likewise policing - again, a last resort, after other arms of the state whose role is to assist people in need have done all they can.

As far as I can see there is substantial evidence that much “crime” is driven by structural societal factors which opens many avenues for mass-scale prevention that could be invested to avoid incidents where people are even tempted to call the police occurring in the first place.

But I’ve never quite been able to push myself to the full abolitionist perspective that prison and policing are entirely unnecessary. Kaba would probably consider that a lack of imagination, which I’m happy to acknowledge. And so this book tries to provide the impetus for a full abolitionist outcome.

There are many aspects to this. Below is my attempt to summarise some of her main points.

The philosophical argument

Philosophically, the author entirely agrees that there should be consequences when people cause harm. However there is a difference between “consequences” that aim to help victims and make society at large and “punishment” that aims in part to make a perpetrator suffer. Sometimes they may look similar, but their goal is different and the latter is inhumane, however attractive it may be to those affected.

But the priority should be addressing the conditions that allowed the harm to take place and the actual needs of the person to whom it was done to. The default of people locking people in cages away from our sight-line is an abdication of the responsibility we all have to help those harmed. It hides important social and political failures.

Furthermore, the system does nothing to encourage accountability. In fact it works against it. People cannot be forced to accept accountability. The current adversarial court system discourages people from taking personal and public responsibility for their actions because it’s almost always in the perpetrator’s interest to deny or minimise the harm the caused, even when they’re fully aware and may like to make some kind of restitution. But if a guilty plea would result in inevitable imprisonment then they may find this unpalatable.

Many “criminals” are in fact victims of something themselves; the victim / perpetrator binary is a fiction. Most women in US prisons are poor, of colour and have experienced physical violence from a partner. Without lessening any harm they commit, we can acknowledge that some criminal actions come from someone making choices that they should never have been put in the position of making.

Hurt people hurt people; desperate people hurt people. Lessening social and economic inequities, and making other, non-criminalising, services easily available could go a long way to preventing the harm in the first place.

Neutralizing perceived threats, in an endless game of legal whack-a-mole, is not a path to safety. To create safer environments, people and circumstances must be transformed.

The legitimacy argument.

Firstly we should examine the definition of crime. It’s often arbitrary. Not everything that is criminalised is harmful. Not all harm is criminalised. A classic example of the latter is CEOs of companies who cause deaths by e.g. harmful, yet perfectly legal, environmental practices.

Additionally, prejudice is rife within the US criminal justice system, notably in the conflation of Blackness with criminality. Black people are more likely to be arrested and more likely to get harsh sentences than white people for the same offence. Black victims of crime are more likely to be ignored.

The current system doesn’t truly even try to meet the needs of victims. Services like counselling, healthcare, housing or money are rarely on offer.

Even in the domain of punishment the victim rarely has the final word. If the system requires the perpetrator to be be jailed then the are, irrespective of the victim’s wishes. The extreme case is someone being sentenced to death (remembering this book is mostly about the US) when the victim is virulent anti the death penalty. They may even feel like they have another person’s death of their conscience unless they drop the charges.

The rise of the “prison industrial complex” has produced economic incentives such for the system to perpetuate itself it needs to increase the number people imprisoned and the duration of their sentences.

Our response to violence and harm should not cause more violence and harm

The efficacy argument

Kaba writes a lot about sexual abuse. This is a crime so pervasive and in some cases so horrific that being seen to argue against an offender going to prison is almost blasphemous even in - or perhaps especially in - liberal circles.

But she raises fair points in that its very pervasiveness shows that the current system doesn’t work Very few reported cases in any case get anywhere near court. Those that do often in reality lead the victim being put on trial more than the perpetrator. These and other factors means who suffer this harm rarely even report it, demonstrating a total lack of faith in the only system that today exists to supposedly help victims of harm.

Harm caused by police officers - sexual misconduct is the second most common form of police violence - is very rarely punished.

The public does not understand the practicalities of policing. Most US officers make just a 1 felony arrest a year. Most of their time is spent dealing with non-criminal issues such as traffic citation, noise complaints or wellness checks. Many of these would be better done by non-police personnel who have better training in for example mental health issues.

In general, there is little-to-no evidence that prisons reduce violence, crime or people’s fear of it. The US prison population increased by over 400% between 1979 and 2014. Neither crime or the fear of crime is 400% lower now.

Some research suggests that going to prison increases the likelihood that you will commit crime again in the future. It’s not clear that they’re even a deterrent in the first place - criminals do not tend to be dispassionately weighing up potential risks and rewards before making their choices.

…a system that never addresses the why behind a harm never actually contains the harm itself.

Reform is not enough

The author believes that reforming the system will never be enough, and may often be counterproductive.

Previous reforms that may have been well-intentioned with regards to reducing the inhumanity of the prison industrial complex system tend to result in little more than more people being criminalised. A historical example is the introduction of women-only prisons and its relationship towards a far greater number of women being imprisoned.

The only reforms she believes we should support are those that reduce the amount of contact the public has with the police and reduce the resources the police have access to. These are steps on the way to full abolition that immediately reduce the harm police can do to people.

She believes that what we need beyond anything is imagination. Her view is that it’s perfectly fine, even necessary, to criticise the system even if we don’t have a fully fleshed out view of an alternative. Measures can be taken now to address issues that we do have solutions for, and real collective effort should be made to figure out the best way forward on those that we don’t.

In the mean time, our lack of imagination has several adverse effects. We imagine that policing, prisons and surveillance are “natural”. This is not true. Prisons are a human invention; in fact a fairly recent one if we consider the current incarnation whose aim is to punish people who committed serious offences by locking them up for long periods of time. These first appeared in the late 18th century; themselves a reform from the previous punishment regime of capital and corporal punishment.

Our criminal punishment system is also contingent on our culture. We tend to believe that our culture is static, even though it never has been. The fear we’re taught to have for each other, the need to bow to authority and celebrate criminalisation of harm-doers is not the only option.

When asked to imagine a world without prisons we tend to imagine the world exactly as today, with the same level of violence, but without prisons. Instead the aim should be to create a different type of society built on cooperation and mutual aid rather than individualism and self-preservation.

My full notes on this book are here.