New Employment Rights Act ‘a huge boost for women in the workplace’: A rare bright spot in the smorgasbord of disappointment from the UK’s Labour government.

Recently I read:

UK must stockpile food in readiness for climate shocks or war, expert warns: ‘The first UK Food Security Report in December 2021 found the country was 54% food self-sufficient’

Latest posts:

Figure is putting ChatGPT brains into humanoid bodies

OpenAI is one of a number of tech companies that have provided sizeable investments into Figure, a company that makes humanoid robots. The creators of ChatGPT will enter into partnership with Figure to develop “develop next generation AI models for humanoid robots”.

Here’s a video showing their progress so far. Finally humanity is one step nearer never having to do the washing up ever again:

It’s uncanny, even though I imagine as per almost all tech demos there may have been a certain amount of fiddling around to make it look cleverer than it actually is. Unlike Elon Musk’s 2021 effort I don’t think this is just a man in a fancy dress costume.

What could possibly go wrong? Just try not to dress them up as cowboys I guess.

In case you’re wondering, no, these robots aren’t chained to the sink for your convenience or safety. Even before the OpenAI involvement they could walk around, heavy objects in hand.

At this point in time though, it’s probably quicker to just make your own cup of coffee.

The Conservative leadership leans into conspiracy thinking

Some of the top British Conservatives seem to be ever more happy to embrace a low-key version of the same kind of conspiracy theories that the Trumpian QAnoners are into.

Prime Minister Sunak seems to believe that the reason they didn’t win a recent byelection in Rochdale was not simply because the performance of him and his party have been terrible enough in recent years that even a bunch of former Conservative voters won’t vote for them, but rather:

Rishi Sunak has said democracy is under attack from far-right and Islamist extremists as he urged the country to unite to beat the “poison”.

Sure, uniting is good, and I’m not at all excited by the result in Rochdale. But it is possible to imagine that “normal” people just don’t like the Conservatives. And it was literally impossible to vote for Labour after they had their own candidate-removing scandal. Sigh.

This fresh after his claim that Britain is descending into mob rule, with the implication that the mob he’s talking about isn’t in fact his own favoured ne’er-do-well political colleagues.

Even less respectably, we have our previous Prime Minister, Liz Truss, sitting down at the US CPAC conference to complain that her plans were thwarted by none other than the “deep state”. And that the civil service is naturally being infiltrated by trans activists and environmental extremists (as if that’d be a bad thing).

She apparently even likes the same kind of media as they typically do:

In an opinion piece published on the Fox News website, the former prime minister said agents of “the left” are active in the administrative state and “the deep state”.

Nigel Farage was also at CPAC of course.

After a trial involving nearly 18000 participants, the US FDA approves Wegovy, one of the famed GLP-1 anti-obesity medications, for reducing the chance of cardiovascular death, heart attack or stroke in adults with cardiovascular disease who live with obesity or overweight. That’s currently most, about 70%, of American adults, although there are a few contraindications.

The Torment Nexus meme

I finally remembered the meme I should have used to describe the concept I was after when recently writing about Replika of “the tech-bro-o-sphere misunderstanding that dystopian sci-fi novels should be taken as a warning, not a product roadmap”.

It’s the Torment Nexus tweet of course!

As Alex Blechman wrote:

Sci-Fi Author: In my book I invented the Torment Nexus as a cautionary tale

Tech Company: At long last, we have created the Torment Nexus from classic sci-fi novel Don’t Create The Torment Nexus

And now there are countless mentions of “Torment Nexus” across the web: “Modern tech is treading some serious Torment Nexus territory”, “Metaverse got torment-nexused just as robot did a century before”, “The Author of Ready Player One Has Launched His Own Torment Nexus”, “And so we come to our latest Torment Nexus, the newly announced Squid Game gameshow” to pick a few high-ranking search results at random.

Per Know Your Meme:

Torment Nexus is used as a metaphor for a thing that was once described as something that, for the benefit of humanity, should not be created, but was then actually created.

The original tweet was likely inspired by Meta’s presentation of their (very grim) metaverse vision back in 2021. But there are so many other examples of the trope available to pick from. One particularly rich source is the ability to pick any episode of Black Mirror involving technology accidentally ruining lives and you’ll likely find someone in Silicon Valley who’s very happy and excited to be working on something similar.

Big Duolingo milestone this week for my mission to learn Spanish:

It’s honestly amazing how bad I can be at something I’ve been apparently learning for a solid(ish) 1000 days. I doubt I could hold the most basic of conversations I know so poco, muy poco, espanol.

The day Replika lobotomised everyone's AI girlfriend

Last year, Gio wrote movingly about the day that Replika turned its AI virtual girl and boyfriends off, and what a cruelty that turned out to be.

It’s an article I find myself returning to whenever I encounter folk who believe there are no real problems to be foreseen with today’s tranche of chatbots. And also when I want an easy example of the tech-bro-o-sphere misunderstanding that dystopian sci-fi novels should be taken as a warning, not a product roadmap.

Firstly, I learned a new acronym. ERP is not Enterprise Resource Planning in this world, it’s Erotic Roleplay - so intimate conversations, sexting, NSFW images, that kind of thing.

The kind of thing in fact that Replika explicitly advertised itself as offering via its AI chatbots. I don’t have a Replika account to confirm with but apparently there were explicit wife and girlfriend modes, as well as friend modes. They advertised role-play, flirting, NSFW pictures from your “AI Girlfriend”. You could even (virtually) marry your AI companion.

Replika advertised itself as being a service for this. They encouraged users to chat regularly, to emotionally and psychologically invest in this digital friend who, unlike ChatGPT et al, was specifically designed give the impression of caring about you.

From one of their adverts:

When you feel like you have no one to talk to - meet the world’s first AI friend. Replika is here to chat about anything, anytime.

So whatever your feelings are about whether these services are healthy, useful, and should exist or not, the point is that it did exist. It was allowed. It was promoted. It was promised. They tried to convince you.

Back to Gio:

Having this emotional investment wasn’t off-label use, it was literally the core service offering. You invested your time and money, and the app would meet your emotional needs.

It turns out that ERP modes, sexual or otherwise, appealed to a lot of its customers. It’s perhaps not surprising that in the current epidemic of loneliness people turned to them, for better or worse. And then one day Replika just turned off those abilities, or as Gio terms it, lobotomised them.

There’s a potential financial bait and switch in this:

It is very, very clearly the case that people were sold this ERP functionality and paid for a year in January only to have the core offering gutted in February.

But also a psychological and emotional one:

People just had their girlfriends killed off by policy. Things got real bad. The Replika community exploded in rage and disappointment, and for weeks the pinned post on the Replika subreddit was a collection of mental health resources including a suicide hotline.

Suddenly your AI wife simply couldn’t express love for you. Some of the testimonials from users that Gio features are quite heart-breaking, even if you don’t think this service should ever have existed in the first place.

For anyone that thinks that having an AI partner is icky, is funny, is to be laughed at, remember that whether or not this service is ethical or should exist - I tend to think it should not, although I don’t know the research on this topic - it did exist. It was promoted, it told vulnerable, lonely people (but not only vulnerable and lonely people) that it would help them lead a happier life.

It’s easy to mock the customers who were hurt here. What kind of loser develops an emotional dependency on an erotic chatbot? First, having read accounts, it turns out the answer to that question is everyone. But this is a product that’s targeted at and specifically addresses the needs of people who are lonely and thus specifically emotionally vulnerable, which should make it worse to inflict suffering on them and endanger their mental health, not somehow funny.

I’m not all that surprised that in the current epidemic of loneliness some folk believed the marketing, signed up, and developed an emotional attachment, just like they were supposed to do. That was the entire selling point of the product according to some of its adverts. In any case, what matters is the negative impact that suddenly withdrawing the service without offering customers any sort of support had. An action that makes people feel upset, even suicidal, taken with apparently no care for those most vulnerable, is at least in part bad.

As Gio notes, probably the real user “mistake” here was to trust a company would deliver what it promised. At the end of the day it was a commercial company that was providing a product. The lack of regulation that exists in this new world so far meant they were entirely free to alter or remove the product as they wished without care to its customers, subject to any existing legislation around misleading advertising and the like at least. For all the talk of safety as a rationale for this decision, the end of the day the average company only cares about its users' well-being to the extent that they it’s a route to getting investors excited. It’s another instantiation of Ezra Klein’s real AI alignment problem.

The corporate double-speak is about how these filters are needed for safety, but they actually prove the exact opposite: you can never have a safe emotional interaction with a thing or a person that is controlled by someone else, who isn’t accountable to you and who can destroy parts of your life by simply choosing to stop providing what it’s intentionally made you dependent on.

…

The simple reality is nobody was “unsafe”, the company was just uncomfortable. Would “chatbot girlfriend” get them in trouble online? With regulators? Ultimately, was there money to be made by killing off the feature?

I’m not sure that I’d be quite so confident saying that nobody was made unsafe through using this product. It’s an open question to me. I’m aware though that some of my reticence here might be a kind of old man “ick” factor. Maybe these things are in fact a useful salve for people’s lonely lives, although I’d hate to see this kind of sticking plaster intervention take the place of a real effort to improve what made us lonely in the first place.

Not of course that Replika is a on a public health mission, nor would we expect it to be. I’d like to see a lot more research into these novel technologies before the capitalists were granted unfettered access to people’s hearts, brains and wallets. Maybe they’re a good thing, maybe they’re a bad thing, maybe they’re good for some people and bad for others. But in this case certainly some users appear to have felt far worse and less safe the day after the decisions was made in comparison to the day before.

What Gio couldn’t have noted in that article, because it happened more recently, was that despite statements from the founder saying “ERP is not returning”, about a year ago naturally ERP did return to Replika. At least for the users who had previously been able to access them having signed up before February 2023. There are plenty of complaints online and particularly in various forums (e.g. Reddit) though that things aren’t quite the same, the characters are still diminished, forgetful, and filtered from their prior state.

And as far as I can tell, it’s now actually once again open to everyone who can afford the subscription. Certainly the current description in the iOS app store makes out that there are no limits:

Create your own unique chatbot AI companion, help it develop its personality, talk about your feelings or anything that’s on your mind, have fun, calm anxiety and grow together. You also get to decide if you want Replika to be your friend, romantic partner or mentor.

…

If you’re feeling down, or anxious, or you just need someone to talk to, your Replika is here for you 24/7.

I would heavily urge everyone to not count on the latter statement being even remotely true. The Samaritans are a far better bet for that.

From The Guardian:

Britain will go into the next general election with taxes at their highest level since 1948

I’m not particularly against well-thought out tax plans or tax increases for those who can afford them, particularly in times of crisis. Taxes are an essential component of any public service or social safety net.

But the Conservatives must not be allowed to get away with pretending they’re some kind of low tax government just because they promote any tax decreasing components of their plans whilst obfuscating the increases.

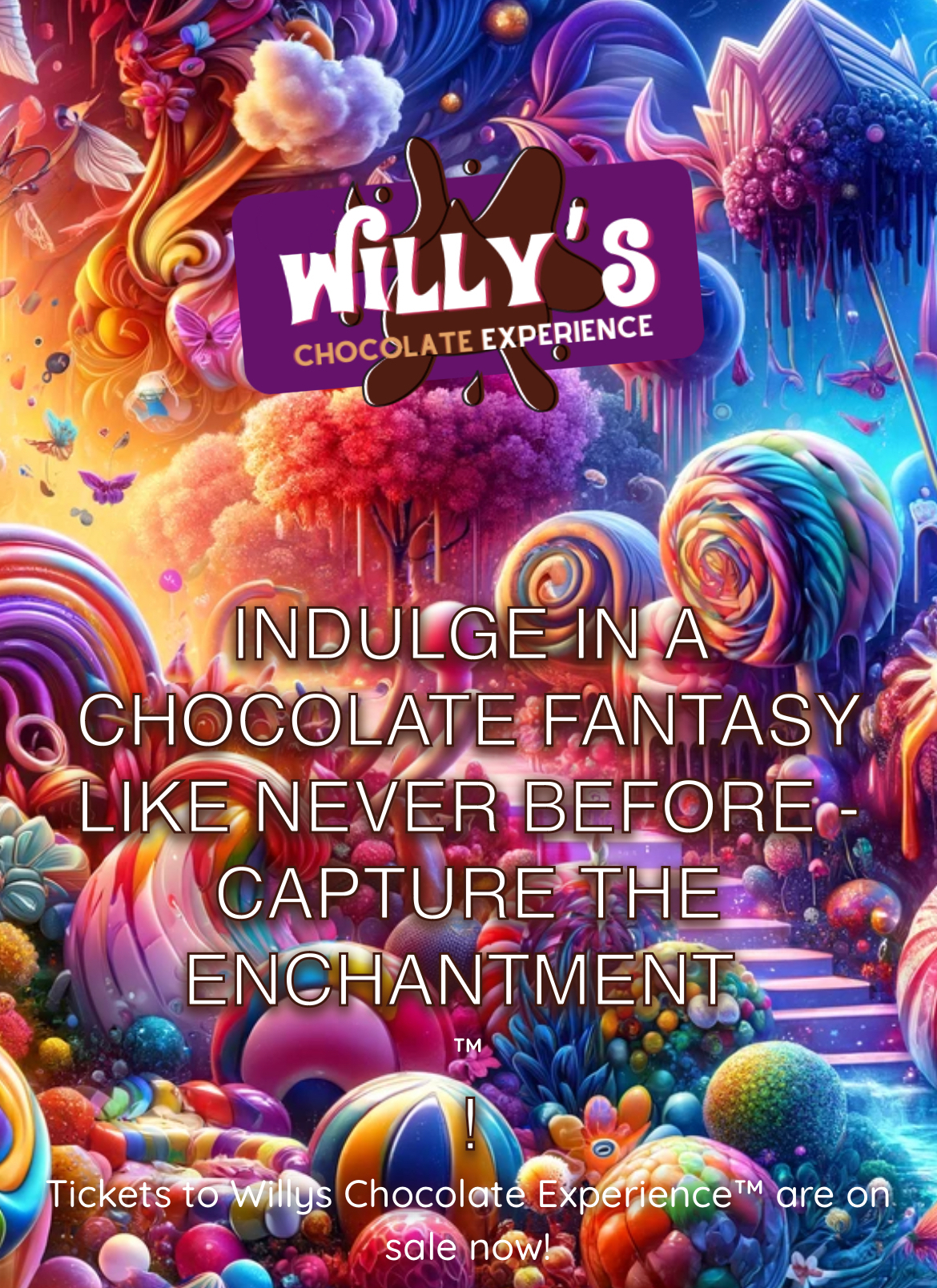

Glasgow’s ‘Willy’s Chocolate Experience’ (as in Willy Wonka of course) seems to have been quite something.

Promising an enchanted garden, magical surprises, optical marvels and an exhilarating adventure, their website markets the wondrous experience like this.

When paying customers turned up they certainly did get a surprise. But more of an utterly miserable, very life-in-2024, one. Here’s a photo.

The displeasure got out of hand enough that the police were called and refunds demanded.

A couple more of my favourite photos culled from the various reports of the occasion.

The PK Cookbook argues for the benefits of a high fat, high fibre, low carb diet

📚 Finished reading The PK Cookbook by Sarah Myhill.

Yes, I actually read a cookbook. To be fair this isn’t the sort of book you would think you were getting if you bought a cookbook. There’s not all that many recipes in it. It’s mainly a description of the how, what and why of Dr Myhill’s favoured diet, the Paleo-Keto (or PK) diet.

-

Paleo, in the sense of a diet that " consists of natural, unprocessed foods and rejects grains and dairy".

-

Keto, as in a diet “that results in the metabolic state whereby the majority of the body’s energy is derived from ketone bodies in the blood - the state of ketosis.”

Overall, it’s basically a high-fat, high-fibre, low-carb diet. You can get a good idea of what the book is about from her website’s wiki, starting here.

An example menu for a day’s food provided includes:

- A breakfast of Coyo natural yoghurt, chia seeds, PK bread and some macadamia nut butter.

- Lunch is mackerel in basil and tomato sauce, avocados and frozen berries as dessert.

- Dinner might be tuna with tomato, cucumber, lettuce, mayonnaise and pine nuts.

Her claims are that, whether you’re suffering from a chronic medical condition or are of good health, then following this diet will benefit your health and longevity. She’s one of those folk appears to believe a change from the typical (western) diet to her favoured one is helpful for almost any malady.

But in particular she claims it to be particularly helpful for people who suffer from conditions such as ME, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or aspects of Long Covid. This includes a lot of people these days. To the best of my knowledge there are as yet few if any generally accepted, proven and effective treatments for these conditions so one can see why people would want to try even rather experimental ideas.

One hellish side-effect of these conditions can be that the person concerned has far too little energy to contemplate cooking up a big pot of stock and baking “PK bread” each day which is really the platonic ideal of this diet. The author reports regularly collecting water from her local spring, harvesting her crops and slaughtering her livestock; surely opportunities not available to the majority of readers. So, to suit the rest of us and especially those suffering with extreme fatigue, the book includes handy shortcuts and an optional pre-written meal plan that’s designed to get one through the first few weeks if you’re in this situation.

This sort of low-effort onboarding is appealing to me. But what’s less appealing to my preferences is that it’s quite hard to fit it into a vegetarian or vegan framework, although reportedly not impossible. I don’t think she thinks those preferences are particularly healthy for a human though.

She warns of an onboarding challenge though - the first few days or weeks are likely to be fairly difficult or painful as your body changes to adapt to its new conditions. As with all restrictive diets, it’s a difficult intervention to stick to, which she acknowledges, but basically says you’ve got to try if you want the benefits.

It must be noted that Dr Myhill is a controversial character. The UK’s General Medical Council banned her from practicing for a while - the most serious reasons for which seem to be around the promotion of “alternative” treatments for Covid-19, and seemingly a general skepticism regarding vaccine effectiveness and safety. These are opinions I struggle to get over. I think they are dangerous. But I suppose even if she’s very wrong about that, it’s possible she might be right about other stuff.

In any case, on the diet front, I’m never going to be someone to tell someone who suffered from an illness that they are wrong if they believe that some intervention helped them even in the absence of conclusive scientific evidence. After all, even interventions that have been designed to have absolutely no biochemical basis for efficacy can help some people with some conditions. There are multiple people who testify to success on this diet. Absence of evidence isn’t always the same as the evidence of absence, although the two can of course coincide.

Of course a different level of evidence should be required - or at least the limitations made transparent - if you’re proselytising an intervention as a panacea for other people. That’s a case which I’m not convinced has been made in this book, even if there are the occasional scientific references given. This diet is counter-intuitive and prescriptive enough that I wouldn’t feel all that comfortable embracing it whole-heartedly without the advice or monitoring from a medic, nutritionist or other knowledgeable person. It’s also not one that everyone will find themselves able to stick with long term; a known issue with the more traditional Keto diet.

Of course it’s also a known and uncontroversial fact that dietary changes in general can greatly improve one’s heath in general or act as treatment for specific maladies. The Keto diet for instance has a long history of success in the treatment of epilepsy for those that find it possible to stick to. I’m not so sure about the Paleo diet - there seems to be less conclusive research (but certainly not none - still, as ever, “more research is needed”) and occasionally a dependency on a kind of appeal to nature in how people speak about it. But some of its traditional recommendations are certainly in line with the mainstream thinking around healthy diets.

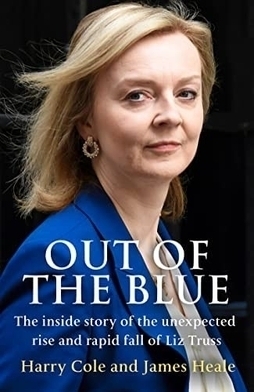

Reliving the story of Britain's shortest-serving Prime Minister with Harry Cole's 'Out of the Blue'

📚 Finished listening to Out of the Blue by Harry Cole.

Cue the obvious jokes about that it must be the world’s shortest book - I suppose it actually is on the shortish side for a biography of a Prime Minister to be fair. It seems that the Telegraph’s suggestion that first draft of the book was submitted with the original subtitle “The inside story of the unexpected rise of Liz Truss” before a matter of days later it became critical to add “and rapid fall” is real. Indeed, you can still find images of the book with both titles out there.

It seems thorough and well-researched enough but I’m not sure there’s a tremendous number of revelations held within it that anyone who kept somewhat on top of British political news in recent years wouldn’t already know. Oddly, it misses out one or two bits and pieces that even very casual observers might have come across; the lack of explicit reference to the Daily Star livestream of a decaying lettuce being one that caught my attention (although it’s very gently hinted at in the intro - that her “seven days in control” is “….the shelf-life of a lettuce”).

But if you too want to relive the highs and lows of Britain’s record-breaking shortest tenure Prime Minister from childhood through to political demise, then this book might satisfy you.

Famously she was an anti-monarchist Liberal Democrat in her youth. Here’s the famous vid of her youth politicking.

Her premiership ended up being disrupted by the sad death of the Queen, leading to one of the finer lines in the book:

Within a week of the last leadership hustings at Wembley, the one-time teenage republican was kissing the hand of Queen Elizabeth II. Two days later, the beloved Monarch was dead;

Let the correlation vs causation debate break forth!

Truss' upbringing was decidedly left-wing. Her mother even moved to try out the communist lifestyle.

In spite of her upbringing as the privately educated granddaughter of a capitalist mill boss, Priscilla was clearly sympathetic to the Marxist cause. After spending time in Prague in the early 1960s, and with a babe in arms, she upped sticks to ‘try out life under the communists’ in 1977.

Life under the communists didn’t last long though, for either mother or daughter.

Whilst her mother retains many of her leftist ideals, Liz Truss comes across as have being as obsessionally wedded to the idea that free markets will solve all of life’s ills from the very start, whilst taxes are the devil’s work in all their forms. I think she’s a true believer, to give her credit, unlike many of her purely-populist libertarian-when-it-suits peers.

When Truss started campaigning in the early 200s it did put her mother in a tricky situation though, a battle between the personal and the political.

But it wasn’t an easy decision for Priscilla Truss, according to a former neighbour, after Liz stood again in 2005. ‘She said she was quite torn. She’d agonised over whether to support her because she was her daughter, or not to support her because she was a Tory. In the end, she decided that family ties should win out.’

Her father did not campaign with her.

Liz seemingly showed great ambition, a tireless fervor and the ability to remain committed to a cause no mater what obstacle or person gets in her way. That, for both the pursuit of her political and personal career goals. No setback was too much for her to come back from. I recall the vibes of even her resignation speech and associated interviews as somehow exuding some “I was right, everyone else is just too stupid to understand” energy. Certainly her book-promo interview in the Mail on Sunday claimed that “the fundamental problem was there wasn’t enough support for Conservative ideas” - but of course it’s the support that’s the problem, not the ideas. Hmm.

This sheer amount of determination, resilience and energy to move forward is surely extremely useful for the successful pursuit of goals - it’s just a shame her goals weren’t something more bearable.

There were nonetheless some aspects of Truss that I hadn’t fully appreciated. But those were more on her personal life and her style rather than her well-documented political accomplishments and failures. I hadn’t understood how obsessed she was with social media, especially Instagram. Call me old but I don’t tend to follow politicians on Insta. But she apparently put some real influencer effort in, continuously focusing on getting the perfect shot even at the expense of tremendous amounts of her team’s time, and in some cases her actual job of attending meetings.

The next stop in Sydney would become a defining image of Truss’s boosterist style of promoting both Brexit Britain and herself. With the rain still pouring, it took many, many goes to get the final snap of Truss on a British-made Brompton bike with a Union flag umbrella in a car park under Sydney Harbour bridge, with the opera house looming large. Freedom of Information requests would later reveal a £1,483 freelance photographer was hired for the trip – but the picture went around the world.

I know you’re dying to see the results, so:

She also seems to have been something of a party animal, fueling her days with espresso and her nights with alcohol. Unlike some of her retinue she somehow appeared to be frequently able to pull off something vaguely day’s work after a night at the clubs though. Not always though, which caused its own problems:

The drinking began at the airport and continued on the plane … her main advisers drank two bottles of champagne on a four-hour flight. On the ground the FS [Foreign Secretary] would drink well past midnight … and be incapable of working the next day. On several trips, Truss would cancel/attempt to cancel important parts of her programme, alienating foreign representatives, due to her hangover or to restart the party.

Honestly it does sound like a pretty fun lifestyle, I’m kind of jealous. If only she wasn’t supposed to be doing something fairly important.

At one point during her tenure as foreign secretary, she, celebrity-like, apparently insisted on in another environment would surely be termed a rider.

…orders were sent ahead to embassies around the world with details of what the Foreign Secretary would expect on a visit:

- Double espressos served in a flat white-sized takeaway cup.

- No big-brand coffee, independent producers only, except Pret if in the UK.

- No pre-made or plastic-packed sandwiches – nothing to be served that has not been freshly prepared.

- Bagels or sushi for lunch – absolutely no mayonnaise on anything, ever.

- A bottle of Sauvignon Blanc provided in the fridge of any overnight accommodation.

And then it all went wrong. Her focus on only the freest of free markets, libertarianism (one of her children is, of course, called Liberty) and her predilection for ignoring everything anyone else would suggest that didn’t perfectly align with her world view led to a catastrophic time for Britain’s economy and a final ousting of its architect, who became Britain’s shortest serving Prime Minister ever after just 45 days in office.

It also introduced (to me) the harshly named economic concept of the moron premium. Per the FT who later went on to try and quantify it a bit:

At the height of the Trussonomics experiment, the additional yield that investors were demanding on government bonds became known in financial markets as the “moron premium”.

Nonetheless, from what we’ve learned of her character in this book and elsewhere, it doesn’t seem likely that she’ll retire quietly into the night.

Disenchanted ex-Vice employees sneak a final podcast episode onto the Cyber feed

🎙 Listening to Cyber: The End of Vice podcast.

Vice Media, owners of such famous media properties as Vice magazine, Motherboard, Vice Sports, i-D and Refinery29 amongst others, announced that it’s laying off hundreds of employees last week.

As the NYT reports:

The cuts will be the latest in a series of severe cutbacks that the company has endured in recent years, winnowing the globe-spanning digital colossus to a husk of its former self.

Some folk aren’t too happy about it, with a general sense that combination of mercenary private equity investors and overly-well paid incompetant top management are, unsurprisingly, happier to cut costs at everyone else’s expense rather than investing in the still well-regarded by many folk company. This to the extent of apparently making the bizarre decision that famed web publishing company Vice will not have a website in the future - no more vice.com, rather a pivot to what feels like a spectacularly ill-timed “emphasis on social channels” .

So a bunch of Vice reporters woke up to discover they no longer had access to Vice’s article publishing system. But someone forgot to take away their access to the podcast distribution feed and so here we are, with what will presumably be the last ever episode of the Cyber podcast, in which the now ex-employees Matthew, Emily, Anna Merlan, Tim Marchman and Mack Lamoureux going rogue and dropping an episode that promises to be full of behind the scenes truth. You won’t find the episode listed on Vice’s Cyber website for obvious reasons, but it should be there in the podcast RSS feed, for now at least.

The layers of the Internet

“The Internet” is just too big and too important to think about as being one thing these days, even if we constrain ourselves to the bits of it that are most popularly used in 2024 (RIP Gopher, Usenet et al for most people, although I suppose hello Gemini?). In considering the impact of things like generative AI, the demise of the original vision of social networks et al I’ve found it far more manageable think of the internet as being layered.

This is a very unoriginal and frosty take. But thinking about what those layers are fixated my attention for a while.

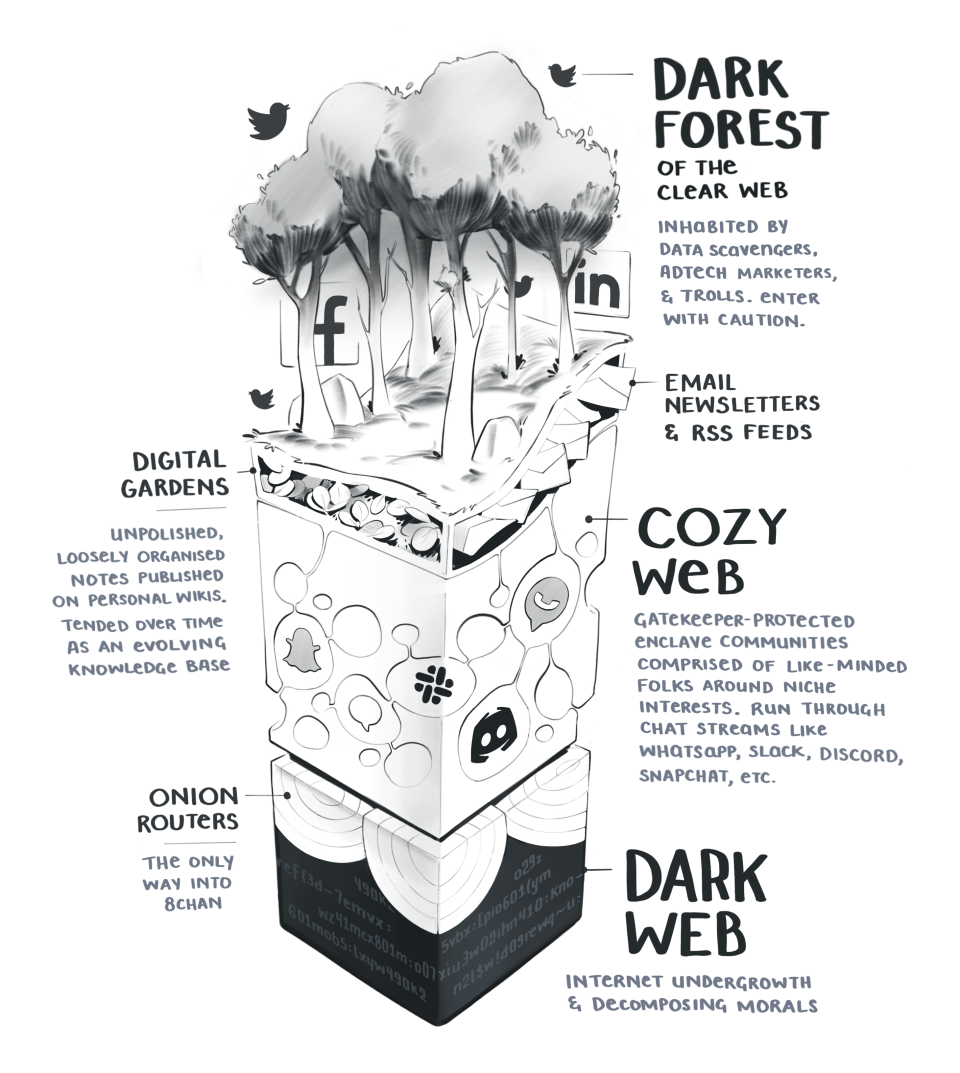

Probably my favourite viewpoint on it, and certainly the most beautifully illustrated one, is Maggie Appleton’s image of “our current social internet situation”.

At the top we have the Dark Forest of the “clear web”. These are your classic websites. The places you usually end up on if you click on the top Google search result, or indeed a lot of Google-owned properties themselves. They’re open to almost anyone with a usable internet connection. In fact they’re often desperately vying for your attention. For the most part they’d in theory be representative of an older, more utopian, vision of the internet - information wants to be free, everyone deserves an equal voice.

…now that most citizens have the tools to engage in mass communication, do more of them have a voice in public debate? Has the web made the public sphere more accessible to a greater diversity of voices?

Many of the web’s early boosters were confident that the answer was yes. Mass media conglomerates would soon dissolve and the net would give rise to an army of Davids.

The only problem is that we’ve ruined it.

From Appleton’s writing:

Most open and publicly available spaces on the web are overrun with bots, advertisers, trolls, data scrapers, clickbait, keyword-stuffing “content creators,” and algorithmically manipulated junk.

By choosing advertising as the currency that underpins the internet, and then creating algorithms optimised to focus your attention on a particular page within the sprawling morass available in an environment where quantity is more predictably lucrative than quality, we’ve ended up in a digital world with where of weirdly worded near-identical sites infused with surveillance trackers between a vomitorium of lurid adverts compete with each other to tell you which mail-order mattress you should buy, invisibly ranked by referral commission, when all you wanted to do was learn how to sleep better. Whilst human writers being replaced by very mid AI text generators is a real and important issue, let’s not forget that there are an indeterminate number of dissatified human writers who are currently paid to write for the AI algorithms in the first place.

I think most of the popular social networks, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter et al. largely fit into this bucket. Oftentimes they require you to sign up in order to access what lies beneath. But they’re generally open to all. At least all who are happy to sign away a vast and unreadable set of rights - the infamous yet ubiquitous “terms and conditions”.

Sometimes their content is indexed and algorithmically hoovered up by search engines and, increasingly, faceless AI bots, in the same way that any other website is. Other times their data is a preciously guarded hoard, unavailable to “outsiders”. But as soon as you sign your various rights away, up until the point where they decide they don’t want you there any more, it’s all there, searchable, exploitable, demanding your attention irrespective of whether you had actually planned to spend the evening watching people scream at each other about whether a school really did provide litter trays for their students who identified as cats (spoiler: they did not) or sing sea shanties.

There’s little incentive to present your whole, honest, self in these places. Your genuine interest in, say, providing a financially secure life for your family will translate to 6 months of every website you visit featuring adverts for the next shitcoin destined to pollute the planet until being rug-pulled away from anyone unlucky enough to have been suckered into the promise of a lifetime of financial freedom.

And if the algorithmised ads don’t get you, the polarised populace of the place may. No-one wants to be the Main Character. Everyone has said something in their lives that if taken entirely out of context and presented in the worst possible light is likely enough for a few million people to hate-scream at you about. And the “here’s something that will annoy you” algorithms will ensure that they are provided the chance to do so.

Why “Dark Forest”? It comes from a parallel Yancey Strickler makes to the amazing sci-fi trilogy (well, I’ve only read book 1, but it was great) “The Three-Body Problem”. In pondering on why humanity hasn’t yet seen all that convincing proof of alien life, Liu Cixin writes:

Imagine a dark forest at night. It’s deathly quiet. Nothing moves. Nothing stirs. This could lead one to assume that the forest is devoid of life. But of course, it’s not. The dark forest is full of life. It’s quiet because night is when the predators come out. To survive, the animals stay silent.

Why no alien visitors to our planet? Perhaps there are no aliens, or perhaps the inhabitants of the rest of the galaxy just know that to speak out, to make contact, invites only risk, only predation. Why is the open web seemingly populated mostly by adtech infused ‘brands’ and extremely partial views of the most theoretically enviable parts of every influencer’s lifestyle? Not because all the real people actually vanished. We didn’t actually turn into one-dimensional caricatures of ourselves. We’re just keeping much of our lives out of the reach of our perceived predators.

So many netizens have slunk away to the cozy web for some respite. The idea that large “open” - well, open only in the sense of letting everyone sign up - social networks are there to connect us with the people we know and love for the betterment of all our relationships has obviously failed. Many of those not still publicly arguing about whether ivermectin cures 5G or how bad their neighbour’s kids are have substantially shifted their focus to places that are less visible, more hidden, less able to have whatever gems of wisdom they contain brutally scraped by Google for it’s publisher-damaging, often inaccurate, “answer box”, or, in more recent times, by hungry AI bots looking for massive training data.

In this category we’re largely talking about chat services; think WhatsApp groups, Discord, or Slack. Often invite only, rarely searchable from the outer world, and - as yet - less infused by bots, humans acting like bots or optimised advertising. It feels easier and safer to build real relationships here; to say what’s on your mind, to talk to people who share your interests.

The downside of course is that they’re generally ephemeral. The wisdom you espouse, the photos of your friends, the stuff you find meaning in there is probably going to have gone, at least in a practical sense, by the time you want to revisit it in the more distant future. Random person X who would have enjoyed hearing what you had to say, but doesn’t happen to be signed up to same same channel of the same service at the same time, is probably not going to be able to. People who never knew others like them existed may never find out that they do if their dialogue is restricted to these spaces.

Information from these spaces is also hard to link to, hard to share with others. Want your friend to see part of a Whatsapp chat or a Discord conversation from a specific channel? Oftentimes sending screenshots, with the commensurate limitations of doing so, is the only practical way. Of course, those same screenshots will themselves become lost over time.

And if the service becomes unfashionable, too expensive or otherwise annoying for the company who runs it - it’s hardly impossible to imagine even the behemoth WhatsApp being shuttered one day by its owner who already had a similar-seeming product when they purchased it if they felt like they could get away with it - there’s a good chance that everything is lost. This stuff doesn’t appear on the Internet Archive. But it’s a safer place to be yourself, to reveal your inner workings, to open yourself up in.

From Yancey Strickler’s “Dark Forest Theory of the Internet":

These are all spaces where depressurized conversation is possible because of their non-indexed, non-optimized, and non-gamified environments.

In Maggie’s words:

We create tiny underground burrows of Slack channels, Whatsapp groups, Discord chats, and Telegram streams that offer shelter and respite from the aggressively public nature of Facebook, Twitter, and every recruiter looking to connect on LinkedIn.

How does it work? From Venkatesh Rao’s formative article, it’s all about very human interactions:

…the cozyweb works on the (human) protocol of everybody cutting-and-pasting bits of text, images, URLs, and screenshots across live streams. Much of this content is poorly addressable, poorly searchable, and very vulnerable to bitrot.

Between the Dark Forest and Cozy Web exists a hybrid category - information available in entirely open formats to anyone who actively requests it, but largely hidden from those who haven’t. It’s often unindexed by the web search engines and fairly inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t know that it exists. Think subscriber-only email newsletters, RSS feeds, that kind of thing. The rise of Substack and its competitors have brought email newsletters to the modern consciousness - although Substack isn’t actually the best example here, as its free newsletters are typically archived as openly accessible webpages too. But the general idea of email newsletters has probably been around for a good four decades or so.

Finally, deep below the Cozy Web, we see the Dark Web. That’s somewhere beyond the typical reach of most humans and their bot counterparts. Its content doesn’t appear on search engines. Clicking on a link in your basic default home web-browser will not get you there. Rather you’d need to get special software and/or authorisation to see it, even if you had a way of knowing it existed in the first place.

Everything’s encrypted. Anonymity is a key value - unlike visiting a surface web, a clear web, website, a darknet site does not know where in the world you’re tuning in from if everything is working well. Tor is probably the most famous of these systems. If you ever see what appear to be weblinks that end in .onion then that’s a Tor site you’ll need a (freely available, one option here - and these days easy enough to use) special browser to access.

This technology clearly has the side effect of making users very hard to police. Thus, unfortunately, much of its content is ethically or legally dubious.

Moore and Rid’s 2016 article Cryptopolitik and the Darknet included an attempt to analyse the content of thousands of .onion addresses and found that:

The results suggest that the most common uses for websites on Tor hidden services are criminal, including drugs, illicit finance and pornography involving violence, children and animals.

The most common commodity they found on sale was pharmaceutical or recreational drugs. The bulk of the finance sites were around Bitcoin-based money laundering, selling stolen credit card details, bank accounts and counterfeit currency. Let’s not spell out what’s encompassed in the third category above.

But don’t get the idea that it’s all terrible - Tor and its ilk provides a way to access information from countries that cruelly block its citizens from being able access much of the conventional internet, including from the likes of Amnesty International . Big news sites like the BBC or The Guardian have a presence. Whistleblowers can share their information with the organisations who can leverage it to make the world a better place, with a higher level of impunity. And, sad to say, some people reputedly find sourcing the drugs they need for their medical conditions easier via these unofficial channels than the methods that in-the-light society has made available to them.

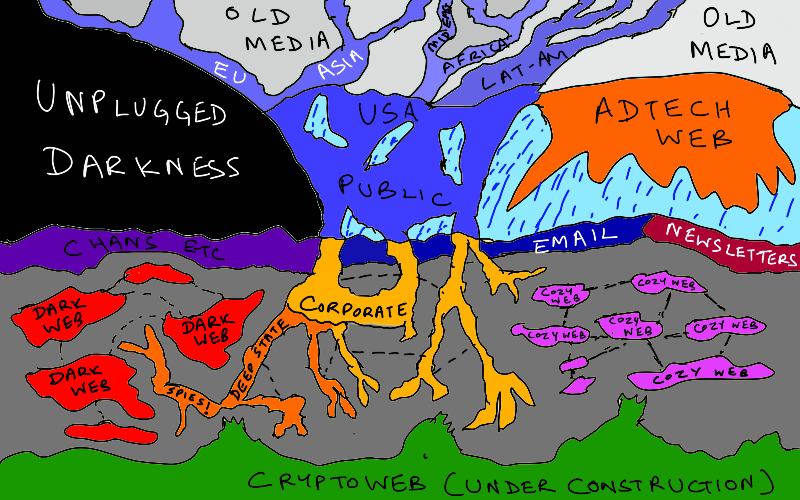

Maggie Appleton credits Venkatesh Rao for the cozy web terminology. Venkatesh himself illustrated his view of the “complexity of the extended internet universe” in what I think is his original post on the matter.

This version, whilst less aesthetically pleasing than Appleton’s beautiful illustration - but still nicer than anything I myself could accomplish - holds two dimensions within it. Imagining it as a two dimensional graph, the horizontal axis moves left to right from sites entirely hidden in the dark through to the “well-lit” conventional web on the right. The vertical axis deals with the level of security the content is held under, from entirely open at the top through to information that’s locked behind complex security technologies and procedures at the bottom.

The x-axis itself is the private-to-public boundary, marked by email for most of us. The y-axis is the high-risk to low-risk boundary, marked by security stronger/weaker than simple passwords for most of us.

There’s not a lot of stuff in the very-private very-visible top left quadrant for obvious reasons - beyond things like accidental data leaks.

Bottom left is the Dark Web, as described above. Full of private information, of secret activity, of often illicit transactions. It’s high risk stuff where privacy is essential for users to complete their goals, but stuffed behind both technological and human security systems far beyond what you’d need to provide in order to log onto Facebook.

Top right is the Dark Forest - the modern-day web, infused with business doing their best to make you see their adverts, to persuade you to buy their wares, to penetrate into your mind, into your email inbox. No security is needed to venture into this content. Everything is in dazzling light, actively pushed onto your eyeballs by search engines, advertising networks, and so on. So much is advertising funded. The more you see it, willingly or otherwise, the more they get paid.

That leaves the Cozy Web, which within this schema is situated in the bottom right. There is a certain amount of security to navigate. You need a special app (e.g. WhatsApp), an account, maybe even an invite. The content isn’t indexed by Google or forced into the faces of unsuspecting ‘X’ users (or for that matter trivially searchable by malicious X users). But when you’re in there, the chat is frequently low risk, stuff that doesn’t feel private in the same sense that your medical records do. It might be your friends' groupchat, which is mostly just all that stuff you’d banter about IRL if you saw each other a bit more, or your colleagues' thoughtstreams - the digital post-pandemic alternative to the watercooler, sanitised in the same sort of way. All in all, there’s no need or active desire to hide this area of the internet from the FBI in the heads of most of its users, it’s “boringly private” to use Rao’s description with both the benefits and drawbacks such an environment brings.

In data breach news, Wyze, a maker of internet-enabled smart security cameras to put in your home, recently had a rather disconcerting security issue whereby thousands of users could see temporarily see footage from other people’s cameras.

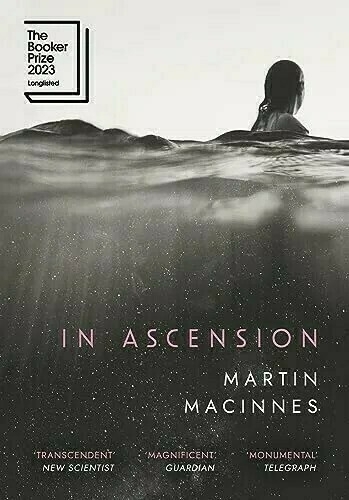

📚 Finished reading In Ascension by Martin MacInnes.

We start by learning about the childhood of our heroine, Leigh. She grew up in Rotterdam, a city surrounded by and threatened by, water - a portent of the future ravages of climate change. Her family life was not at all what one would hope for.

Years later though, she’s gotten out of it all. Life amongst water surely influenced her though. She studied as marine biologist, and later gets involved in a ship-bound expedition to investigate what appears to be an unprecedented anomaly discovered in the ocean.

One thing leads to another, and she’ll eventually get involved in a mission to investigate another anomaly, one much further away. Nonetheless, no far how far away you go, it’s impossible to entirely evade the more conventional trials and tribulations of day-to-day life as a human.

The book has been described as genre-defying. In part it’s pretty sciencey science-fiction, something that based on some reviews I’ve seen not everyone gets on well with. But it never strays far from much more human topics; psychology, connection, relationships functional or otherwise. There’s ever present mysteries, meditations on Big Questions, and just enough ambiguity to be memorable and engaging rather than frustrating.

It’s beautifully written, conveying well a real and detailed sense of the wonder and majesty of the natural world, the wider ecology, and humanity’s place within it. Profound, philosophical and truly fascinating; justly longlisted for the Booker Prize. I now want to read all the author’s other books.

Apparently even more British children have smartphones than I’d have guessed.

Ofcom data says 97% of children have one by the age of 12

The idea of introducing some official guidance on a “ban” (severity left up to discretion) on kids using them in schools seems like a reasonable idea to me, even whilst already many schools do this.

I’d love to see a life-lesson on “how to use your phone in a way that doesn’t negatively impact your life” introduced too. If anyone actually knows how to do that.

Air Canada instructed to honour a refund that their chatbot inadvertently promised

From Ars Technica:

After months of resisting, Air Canada was forced to give a partial refund to a grieving passenger who was misled by an airline chatbot inaccurately explaining the airline’s bereavement travel policy.

This feels like a good, important, decision. Would Air Canada have fought so hard if it was a human customer service agent that misled the company? There is no practical difference to the customer. Although to be fair, the ruling suggests that maybe they would have, with the remarkable line that:

Air Canada argues it cannot be held liable for information provided by one of its agents, servants, or representatives

In which case why even have a customer services department? Are you supposed to be able to guess whether or not an agent is telling the truth every time you call them up?

In this case it’s not like we’re talking about something that threatens the existence of the company. Air Canada, a company that measures its quarterly revenue in billions of dollars, isn’t going to go bankrupt if they give the customer the $880 refund he was expecting.

In any case, if a company is going to replace its human customer service agents with chatbot customer service agents then they should surely be equally as liable for any misinformation.

As the judge notes:

In effect, Air Canada suggests the chatbot is a separate legal entity that is responsible for its own actions. This is a remarkable submission.

If we want to regard chatbots as being “responsible for their own actions”, well, some kind of radical legal shift would presumably be needed. It’s also kind of insane. If chatbots have responsibilities then do they also have rights? Do we put them in chatbot jail if they say something wrong?

If what they actually mean is that whoever sold them the chatbot should be held responsible, well, there are surely already legal routes that can be used by Air Canada to claim damages against another company if they believe they’ve been mis-sold something.

In no circumstance should it matter than the actual bereavement policy was somewhere else on their website. It’s not the customer’s responsibility to research the same question several times and try and guess which version the company actually meant to provide.

More from the ruling:

While a chatbot has an interactive component, it is still just a part of Air Canada’s website. It should be obvious to Air Canada that it is responsible for all the information on its website. It makes no difference whether the information comes from a static page or a chatbot.

While Air Canada argues Mr. Moffatt could find the correct information on another part of its website, it does not explain why the webpage titled “Bereavement travel” was inherently more trustworthy than its chatbot. It also does not explain why customers should have to double-check information found in one part of its website on another part of its website.

Another 'abuse of power': thousands of students wrongly deported from the UK for supposedly cheating on a test

This multi-year miscarriage of justice is embarrassingly new to me, but then again so was an event that it has recently been compared to - the Post Office Horizon scandal.

A decade ago, one condition for foreign students who applied for a visa to come study in the UK was that they first had to pass a specific English test called the Test of English for international communication or Toeic. Although I haven’t seen the questions, it sounds like it’s quite basic, something that anyone reasonably fluent in English would do OK at. It’s intent is merely to “measure the everyday English skills of people working in an international environment” rather than check whether you’re PhD-level familiar with the literature of the English-speaking world.

The Home Office authorised 4 approved test providers that students could use to do this. One of these was US-based company, “Education Testing Service” aka ETS.

Back in 2014, TV show Panorama found that there was cheating going on in a couple of their centres. As far as I can tell everyone agrees that this part is true: cheating definitely went on in 2 of around 90 centres ETS ran.

But rather more controversial was the follow-up investigation that claimed that of the ~58,000 students who sat that test in their centres over a 5 year period, over half “had used deception” and another 39% were questionable, entirely on the basis of some unspecified voice recognition technology analysis. Yes, the claim was that 97% of entrants cheated.

Consequently, these students had their visas revoked. This made it illegal for them to remain in the UK. At best they could hope to be simply thrown out of their (expensive) university courses. At worst some were locked up in detention centres and eventually deported, only to live a life in disgrace as their nearest and dearest were led to believe they were nothing but a foolish cheat.

From politics.co.uk:

Then people started being rounded up. Families were woken in dawn raids, the husband separated from the wife and sent to detention centres ahead of deportation. It would have been a profoundly harrowing experience. These were students, not criminals. Their only crime had been to do a test recommended by the Home Office. But the full sadistic force of the state was brought down upon them.

Not even a entitlement right of appeal was given at first, at least without having first left the country.

All in all, 2500 were forcibly deported and another 7.2k have left the country after being threatened with arrest. Others have ended up destitute and homeless, depressed or suicidal.

Since then at least 3600 of those students have won immigration appeals, although the public records don’t specify whether that’s because they’ve been found to be innocent of cheating or for some other reason. But it was certainly the supposed cheating that put them in the position of needing an appeal in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, many of the students have claimed they are entirely innocent and that any supposed evidence against them is extremely weak. The Home Office hadn’t previously acknowledged let alone taken action based on that. But they were certainly aware of the issue.

In 2019, the National Audit Office found that the Home Office didn’t have the expertise to validate the evidence provided by ETS, and that it had simply taken it at face value. They’d made no real effort at all to investigate whether or not the accused had been incorrectly classified as cheats

Even earlier, in a 2016 tribunal case that challenged the actions of the Home Office on these matters, the presiding judge found that none of the people representing the Home Office:

had “any qualifications or expertise, vocational or otherwise, in the scientific subject matter of these appeals”. At no time, in fact, had the Home Office had advice or input from a suitable expert. The criticisms of their witness statements “were not addressed, much less answered, in their evidence”.

and that:

The Home Office’s case that these students had committed fraud was “entirely dependent” on ETS. The tribunal found the Home Office accepted uncritically everything reported by the firm.

One of the complainants in that case, a Mr Qadir who had been accused of cheating the test, of course spoke “excellent English” when testifying.

Thousands of the other accused people were waiting on the results of this case to use as evidence in their own appeals. Some of their cases had specifically been put on hold until this tribunal’s verdict was out. However, at the time the committee refused to report on their findings, as important and universal as they were, making it very difficult to cite elsewhere.

The decision means that the case cannot be cited, except under very strict and laborious conditions, in other appeals. It means many thousands of people who have been unjustly deported will not even know of its existence. The decision makes the ruling against Theresa May legally useless. It’s as if it never happened.

Lawyers went on to accuse the committee of “an abuse of power”, with their decision to not publish what went on as being “plainly hostile to common sense”. Accusations flew that the decision whether to publish or hide the proceedings of the cases seen by this committee were very much dependent on whether the case showed the Home Office in a positive light.

The years this was all happening in were well into the still-ongoing inhumane period where the at-the-time British Home Secretary Theresa May was explicitly trying to create a “hostile environment” in theory for illegal immigrants, but in practice for anyone that in any sense didn’t “look British”.

Being able to tout ever bigger numbers of punishments against and deportations of immigrants who were in Britain illegally - the situation these poor students found themselves in when stripped of their visas due to having been accused of cheating on a test - was exactly what the government, particularly the Home Office, would have wanted. Clearly there was little incentive - outside of, you know, the basic tenets of justice and humanity - for May’s department to look into it.

May now regrets the phase “hostile environment”, but so far that doesn’t seem to have helped many of the folk who unjustly suffered, nor lessened the hostility of the environment itself.

The “97% of people are cheats” figure just seems prima facie implausible to me. Surely it’s well beyond the threshold that basic common sense should have caused an immediate halt to the punitive proceedings and further investigations to have urgently been done a decade ago.

In the unlikely case that cheating was really that endemic, there have also been scenarios suggested whereby it may have been the centres, rather than the students, that were cheating. And if it had turned out that 97% of individual students had cheated, well that surely points to a systemic problem with the structure of the testing regime than something individually defective about almost every single person who took the test.

But, in any case, that’s all a meaningless thought experiment when it seems like there’s no real evidence that cheating on anything like this scale ever happened in the first place.

Also to add to the mix: the inconvenient fact that several of the students entangled in this mess were provably perfectly fluent in English well before they took the test. To the extent it’s basically inconceivable that they could have failed what is a fairly basic test. Hence there would be absolutely no incentive for them to have paid someone else to take it for them, which is generally the allegation being made, or engage in any other such nefarious scheme.

One such example of this is poor Kishor. He successfully completed a degree in English literature, worked as an English teacher, and worked with NATO troops in Afghanistan, which required passing an English test, before coming to the UK to pursue a business degree which is the point at which he took the Toiec test. He probably speaks better English than I do. Nonetheless he was amongst the crowd that were accused of cheating.

Learned a new phase last week: stinge-watching.

It’s the opposite of binge-watching. Particularly for the cases where you could in theory binge all episodes right now just like the streaming services want you to do but instead you go out of your way to space them out.

📺 Watching The Apprentice - season 18.

It’s sometimes reassuring when things stay the same - and here once more we have a bunch of buzzword-laden people, with apparent levels of self-confidence most of us could only dream of, doing whatever it takes to impress the master of awkwardly delivering badly-scripted jokes and pointing at people, Lord Sugar, all in the name of getting an investment.

I was just looking up the iconic 2010 contestant Stuart “The Brand” Baggs to be sure of getting his justifiably famous quote right - ‘I’m not a one-trick pony. I’m a whole field of ponies’ - only to discover that sadly he died in 2015, aged just 27. Lord Sugar left a floral tribute.

Another thing I recently learned is that in order to keep who wins a total secret until broadcast, the show apparently films two different endings, one where each of the two finalists win and the other one loses. Even the two candidates concerned don’t learn who won until much later - the day before the final show is broadcast. Same for the production team.

Sometimes even the same ending has to be filmed more than once. Harpreet Kaur, the winner of the 2022 season, had to have her “winning” ending filmed twice because she didn’t have “the right level of excitement” the first time through. I suppose it is probably hard to muster the TV-level appropriate extremes of performative excitement when there’s a good chance what you’re celebrating never happened. I’m not sure how she reconciles that with her quote in the same article that “there’s no acting” in the Apprentice, but there we go.

I’ll watch with interest when it’s time for the 2024 final to see if this cohort’s acting-like-a-winner skills are better than one might imagine.

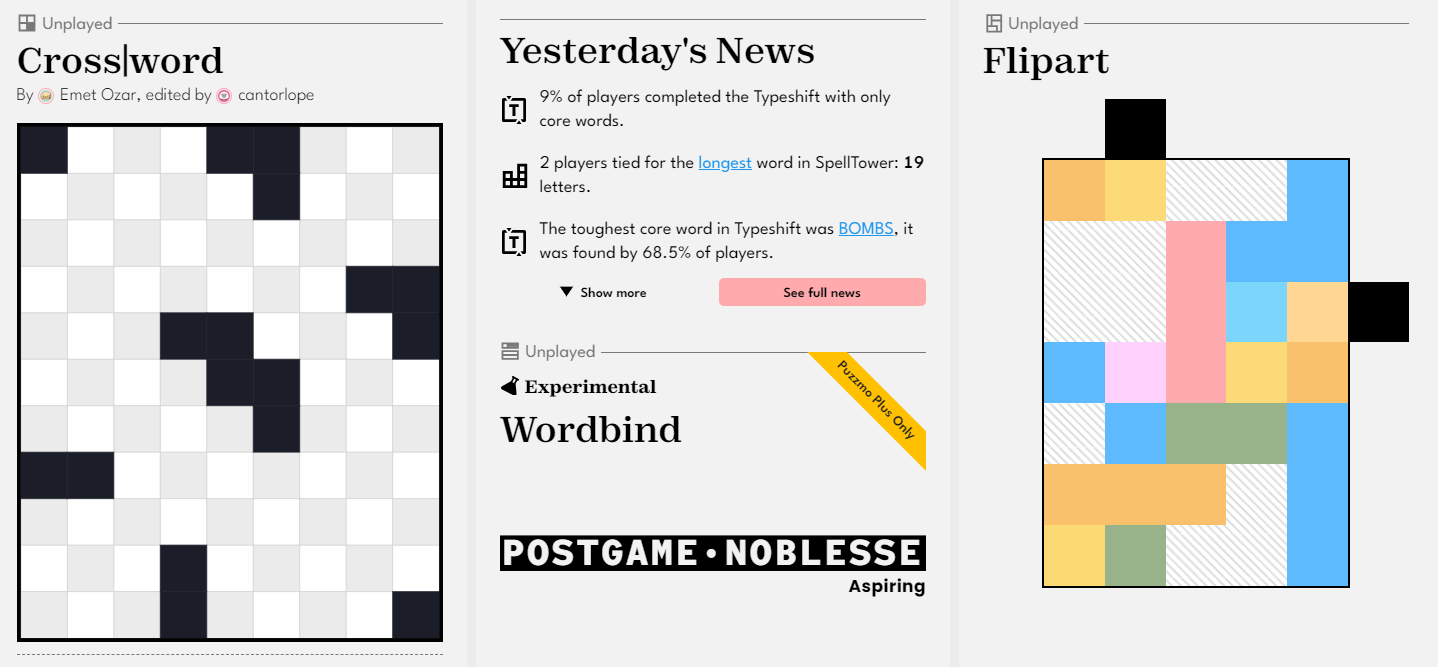

For anyone that finishes Wordle too quickly, Puzzmo - “the (new) place for thoughtful puzzles” - looks to be a cute ‘n’ fun newspaper-puzzle-page style site.

It’s got the classic crosswords, slightly reimagined for the digital age, along with a mass of other puzzle types, old and new. A good chunk of it is entirely free to play. Not sure how to fit more puzzles into my life, but it’s pretty fun and that’s even before experimenting with the interesting sounding “play with a friend” options.

Their manifesto is also pretty cool. You deserve better, you are smart, play is healthy - all good affirmations.

They’ve also already been acquired apparently. That was quick. Let’s hope (against all hopes?) it doesn’t tarnish the original vision. First up it seems like they’re offering revenue-share collaborations with other “brands” - that’s why for instance you could choose to do the same puzzles alongside Polygon branding if you really want to.

Here’s an embedded “Spelltower” puzzle to keep you busy. Click and drag the letters to form words, submit by clicking on the last letter again, in order to clear as many letters as you can.

TIL: Elon Musk wasn’t the founder of Tesla. Tesla’s real founders were Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning.

Musk was merely an early investor in the company. Who seemingly started out as he meant to go on.

From The Verge:

Musk was brought on as a crucial early investor but soon used his clout, money, and even a few strong-arm tactics to oust Eberhard and Tarpenning and eventually install himself as CEO of Tesla.

Eberhard ended up suing Musk for all manner of things: libel, defamation, breach of contract, infliction of emotional distress, and failure to pay his wages, The only reason Musk is even allowed to call himself the founder of Tesla is because he effectively purchased the right to do so as part of the legal settlement.

Interesting that “social media” is such a toxic brand these days that Snapchat’s recent marketing campaign is all about how Snapchat very definitely isn’t social media

In fact, it was built as an antidote to social media

This is rather different to how they previously touted it, at least to organisations who might want to pay them something. Less than one year ago they were busy business-blogging that you should throw your advertising dollars their way given that:

Snapchat is a prime example of a social media platform.

NearbyWiki.org is a fun site that plots Wikipedia encyclopedia entries over an interactive map. You can then, for instance, see what stuff-famous-enough-to-be-on-Wikipedia exists near where you live.

One thing this led me to learn is that there are a lot of entries for pretty unexciting roads on Wikipedia. I suppose there are about 262,300 miles of them to go around in the UK.

📧 Reading the Bits About Money newsletter.

I’d never spent too much time thinking about how the financial infrastructure behind organisations such as banks and payroll providers was set up. It turns out it’s pretty interesting to read about, and may even help explain a lot of the weirdness about how such organisations treat customers.

All previous issues live here if you’re more of a web-reading fan.

TIL: Buckingham Palace pays a council tax bill of £1,828 per year.

That’s lower than 46% of households in the UK according to The Economist, who rightly argue that the whole system needs a shakeup for reasons beyond palace inequities. It’s an extremely regressive tax as it stands.